Страстная пятница в христианстве — время скорби и траура. По Библии, в пятницу, следующую за Тайной вечерей, Иисус Христос был осужден и распят на кресте. В этот день верующие вспоминают о страданиях Спасителя.

Когда наступит Страстная пятница в 2023 году

Страстной, или Великой, называется пятница последней, шестой недели Великого поста, непосредственно перед Пасхой. В 2023 году Светлое Христово воскресенье в православии выпадает на 16 апреля. Соответственно, Страстной будет пятница накануне него, то есть 14 апреля.

Католическая Пасха в 2023 году отмечается 9 апреля. Таким образом, датой Страстной пятницы в этом году в католичестве станет 7 апреля.

Кстати, иногда даты Пасхи, а следовательно, и Страстной пятницы, в православии и католичестве совпадают. Такое произошло, например, в 2017 году, когда Светлое Христово воскресенье выпало на 16 апреля.

Вспомним Евангелие: Страстная пятница в христианстве

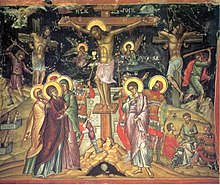

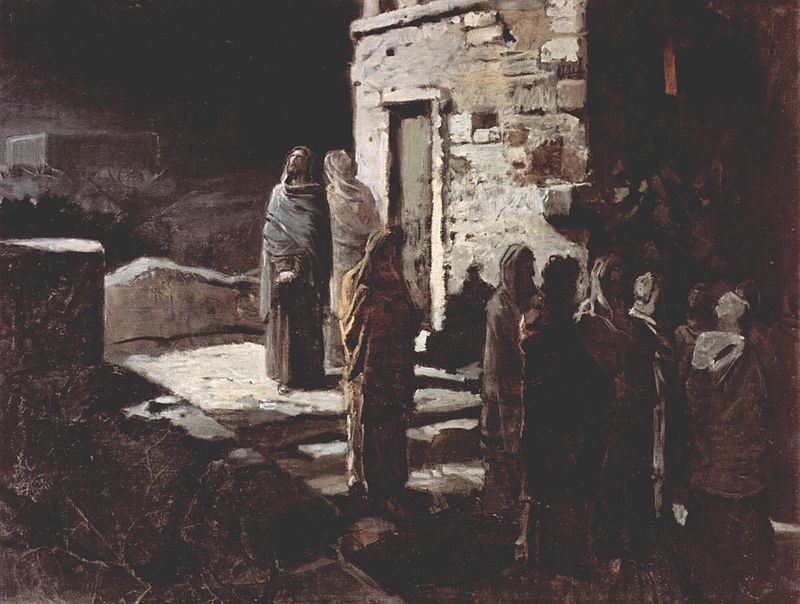

Согласно Евангелию, в пятницу преданный своим учеником Иудой Христос предстал перед судом прокуратора Иудеи Понтия Пилата по обвинению в бунте и подстрекательстве. Пилат, осознавая несправедливость этих наветов, тем не менее приговорил Христа к казни через распятие на кресте.

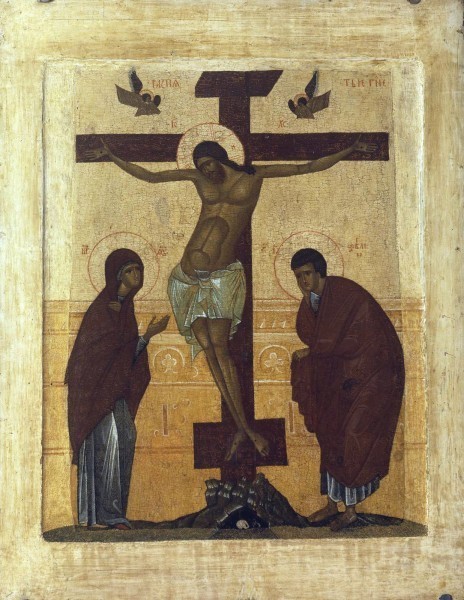

Казнь состоялась на горе Голгофа, при этом крест, на котором, его распяли, Христос нес по улицам Иерусалима сам в сопровождении стражи. Одновременно с Иисусом там же были казнены двое разбойников, причем один из них раскаялся в своих грехах.

Как далее повествует Евангелие, на третий день после смерти на кресте Христос воскрес. Это воскресенье стало главнейшим праздником в христианстве, Пасхой.

Страстная пятница в православных и католических храмах

Богослужения в Страстную пятницу посвящены повествованиям о муках Христа на кресте, его смерти и погребении.

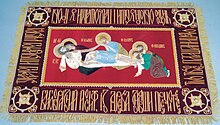

Во время православной вечерни (фактическое время этой службы — около 15:00) поется особый канон, а из алтаря к верующим выносят плащаницу, изображение Спасителя во гробе. Это действие стали включать в вечерню только с конца XVI века, а сейчас оно является обязательным. В центре храма Плащаница находится три неполных дня.

В католичестве принято богослужение Крестного пути, которое напоминает верующим об основных моментах страданий Иисуса по дороге на Голгофу, и особая вечерняя служба Страстей Господних (после 15 часов дня, времени смерти Христа по Библии).

Как правильно провести Страстную пятницу

Великая пятница — день самого строгого поста в христианстве. Верующие полностью отказываются от пищи до времени выноса в храм плащаницы, но и с этого момента разрешаются только вода и хлеб.

Так как Страстная пятница — время траура и скорби, в этот день особенно не рекомендуется предаваться веселью. Вместо развлечений лучше сосредоточиться на молитве и помощи близким.

Народные традиции в Страстную пятницу

Помимо христианских традиций, для Страстной пятницы существовали и народные обычаи, перекликающиеся с суевериями и нередко вообще имеющие языческие корни. Например, на Руси иногда жгли на высоких пригорках костры, защищающие, по поверью, от нечистой силы. Также был распространен запрет на земледельческие и кузнечные работы. Женщинам надлежало отказаться от шитья и вязания, да и все остальные работы по дому хорошо нужно было закончить в Великий четверг. А вот печь, напротив, рекомендовалось: считалось, что приготовленный в этот день хлеб сможет излечивать болезни.

В некоторых странах в Страстную пятницу проходят театрализованные шествия, которые, впрочем, далеко не всегда одобряются церковью. Например, в филиппинской деревне Сутуд несколько десятков лет практикуются ритуалы распятия и самобичевания, и посмотреть на них приезжают туристы-католики со всего мира. А в Мексике Великая пятница — день карнавала и спектаклей по мотивам евангельских сказаний. Эта традиция пошла еще с колониальных времен, когда прибывшие в Америку испанцы стремились обратить местное население в христианство, а яркий праздник служил для привлечения внимания.

Пасха

Страстная пятница перед Пасхой

Содержание

- Что это такое?

- Традиции

- Пост

- Что можно и нельзя делать?

- Обряды и ритуалы

- Народные приметы

Страстная неделя перед Пасхой – это последняя неделя Великого поста, предшествующая празднику. Итогом становится Страстная пятница. Рассмотрим, что разрешено делать в этот день, а что находится под запретом.

Что это такое?

Страстной или Великой пятницей перед Пасхой называется тот день, когда судили Иисуса Христа, когда произошли его распятие на кресте и смерть. В тот же день его тело сняли и совершили погребение. Вся эта история записана в Библии.

Все дни последней недели называются страстными. Например, Страстной четверг или Чистый четверг. Это означает, что в четверг принято наводить чистоту в доме. Таким же образом говорят про пятницу, субботу. Иногда эти дни накануне праздника называют Великими. Иными словами, особо почитаемыми в христианстве.

Говорят, что после трагического события камни, набросанные у креста, раскололись, а день сменился ночью. Люди, наблюдавшие за этим, испугались. У многих пришло верование в то, что Христос – сын Божий, а не аферист, в чем его обвиняли. Но Христос простил людям все их прегрешения, потому что его последними словами было: «Прощаю их, они не ведают, что творят».

Именно в Страшную пятницу православные чтят поступок Бога. Везде проходят богослужения, для многих пища под запретом. Они благодарны Христу, готовы разделить страдания Святого, отказаться от естественных потребностей.

Традиции

В этот день хозяйки начинают печь куличи, красить яйца. По дому все дела уже сделаны: уборку делали в Чистый четверг. Согласно традиции, если наводить чистоту в пятницу, то можно привлечь к себе беду и совершить грех. В пятничный день нельзя употреблять алкоголь, заниматься плотскими утехами. А все юбилеи и дни рождения, приходящиеся на такой день, стоит перенести. Под запретом раздражение и ругань. Пересуды, разговоры, пустые сплетни недопустимы. Что касается пищи, то в этот день лучше не употреблять яйца, мясо, рыбу, молочные продукты.

В вечернее время в четверг все храмы проводят утреннюю службу Великой пятницы. Основная молитва – 121 Страстных Евангелий, где описаны все страдания Господа. У православных в руках зажженные свечи.

Если свеча не потухла, то ее несут домой и воском рисуют крест на двери. Считается, что такой знак убережет от всего нечистого. Пятничной литургии не бывает, но читают Царские Часы. К 15.00 часам выносят Иисусову плащаницу в центральную часть храма.

Пост

Согласно церковным канонам, для Страстной пятницы есть свои запреты и одобрения.

Употреблять можно следующие продукты:

- чай на травах, но без сахара;

- сырые фрукты и овощи;

- сок из любых фруктов и овощей;

- консервированные или моченые овощи и фрукты.

Это меню для постных дней: выпечка, алкоголь, мясо, рыба находятся под запретом. Говорят, что если человек постится, то его пятничный рацион – кусок хлеба и стакан воды. Строгих запретов на приготовление пищи нет: многие хозяйки готовят традиционные блюда для пасхального стола. Хотя перед такими соблазнами и запахами мало кто устоит.

Согласно библейским канонам, Иисус Христос умер в 15.00 часов. Исходя из этого истинно верующие люди до указанного часа вовсе не принимают пищу, не пьют воду.

Конечно, это довольно строгие запреты, не каждый может соблюдать такие предписания. Но следует понимать, что такой скорбный день в году бывает единожды, и к нему желательно подготовиться заранее.

Есть послабления для некоторых категорий людей:

- малыши и младенцы;

- кормящие мамы, женщины, которые ожидают пополнения в семье;

- пожилые люди;

- граждане, которые имеют хронические, тяжелые и неизлечимые заболевания;

- те, чей труд связан с тяжелейшими физическими усилиями.

Как утверждают священнослужители, даже если человек не соблюдал пост с самого первого дня, то он может присоединиться в любой момент. Для этого нет никаких запретов.

Что можно и нельзя делать?

У верующих много вопросов по поводу того, что можно и нельзя делать в пятый день. Представители церкви утверждают, что это лучший день, когда можно поразмышлять о подвиге Христа. Лучше всего сотворить благое дело или подать милостыню. Обычно православные посещают родных людей, прощают обиды, примиряются. Иными словами, свобода выбора всегда есть, но намерения должны быть благими. Важно правильно провести этот день, прожить его согласно христианским канонам.

В эти дни можно:

- участвовать в выносе плащаницы;

- молиться, стоя перед иконами;

- читать молитвослов;

- изучать законы Библии;

- посещать храмы;

- думать и размышлять о судьбе Господа;

- ограничивать себя в пище;

- ходить на исповедь;

- возносить благодарные речи Господу;

- печь куличи, готовить праздничную еду, если не успели ее сделать накануне;

- просить о прощении грехов.

Можно плакать и грустить, но только если такие эмоции вызваны мыслями о непростой судьбе Иисуса Христа. А вообще дома нужно соблюдать тишину и покой. Это не выходной день, и от обязанностей идти на работу никто не должен уклоняться. Но на Руси были свои запреты.

- Не трогать землю. Все работы такого плана находятся под запретом. Рубить дрова также считалось делом грешным.

- Не заниматься рукоделием.

- Нельзя печь, прибираться, стирать, проводить уборку дома.

- Не рекомендуется купаться, стричься. Даже баню топить было запрещено.

И уж ни в коем случае нельзя пить алкогольные напитки, смотреть развлекательные передачи, ходить в увеселительные заведения. Не приветствовались прием друзей или поход к ним. А в храмах отменялись венчания.

Обряды и ритуалы

В Страстной день обычаи и заговоры имеют силу. Верующие во всякого рода ритуалы пытаются привлечь удачу, улучшить свое положение с финансовой точки зрения. В это время магия сильна, а желания и просьбы сбываются. Согласно обычаю, Пасха и магические обряды несовместимы. Но такая практика присутствует. Рассмотрим самые популярные верования.

- Неслучайно многие люди после службы приносят домой горящую свечу. По количеству их должно быть 12. Пока человек идет домой, свеча должна гореть. Если она потухла и ее снова зажгли, то исполнения желаний, улучшения положения ждать не стоит.

- Нужно было во время службы освятить любое кольцо: оно должно было потом оберегать всю семью от несчастий.

- Свечи нужно поставить перед иконой, там они и должны прогореть. Только тогда в дом прибудут счастье и достаток. А богатство и успех будут с человеком весь год.

- Это время, когда знающие люди заговаривают вещи и подкидывают их своим недругам. Чтобы найти подклад, нужно в церкви взять не горящую, а догоревшую свечу, принести домой и снова зажечь. Рекомендуется обойти все комнаты в доме: там, где свеча начнет коптить и трещать, и лежит подклад.

- Считается, что именно в такие дни можно излечить человека от пьянства. Нужно взять золу, положить ее в кулечек. Необходимо дождаться ночи и у перекрестка разбросать ее с пожеланием того, чтобы человек почувствовал отвращение от алкоголя.

- Незамужние девушки очень ждали такого дня. Накануне они делали уборку в домах, а рядом со своей полочкой оставляли много пустого места. Считалось, что так они зазывали суженого.

- Говорили, что если ранним утром в Великую пятницу девушка увидит птичку у окна, то скоро она познакомится со своим будущим мужем.

- Для привлечения финансовой удачи к закату дня опускали на дно емкости серебряную монету, заливали родниковой водой. Наутро монетку отправляли в кошелек и носили весь год, а воду эту выпивали. Тогда деньги водились все время.

- Говорили, что если разбить зеркало, то деньги пропадут. Все финансовые расчеты переносили на другой день.

- Дурных предсказаний и предзнаменований можно было избежать, если утром до зари обтереть косяки да углы дверей новыми полотенцами. После советовали убрать полотенце в потайной угол, сохраняя весь год.

- Для того чтобы сохранить мир и спокойствие в доме, хозяйка должна была испечь два каравая, а перед замесом попросить Господа о сохранении своей семьи да помолиться. Когда хлеб выпекался, один каравай съедали семьей, а второй хранили за иконами в течение всего календарного года.

Народные приметы

Спустя долгое время у народа появились свои приметы и суеверия на Страстной день. К примеру, говорят, что хлеб, который пекут в этот день, не плесневеет и имеет целебную силу. Говорят, что такой каравай способен защитить дом от несчастий, а человека в пути – от болезней. Хорошим знаком считалось, если хлеб, испеченный на тот момент, получался красивым, мягким да с румяной корочкой. А если хлеб не пропекся или сгорел, жди беды.

Рассмотрим и другие народные приметы.

- Веселье и смех в тот заветный день были под запретом. Кто засмеется на пятницу, тот плакать весь год будет.

- Горе случится с тем человеком, который посмеет землю чем-либо проткнуть. Даже растения высаживать нельзя: они все равно погибнут. Но может порадовать хорошим урожаем петрушка.

- Нельзя на землю плевать, иначе все святые на тебя ополчатся.

- Сколько не стирай одежду по пятнице, она все равно не станет чистой.

- Говорят, что тот, кто пьет на пятницу, тот быстро сопьется, а если зачать ребенка в те дни, то болеть он будет или еще какое несчастье с ним случится.

- Но отлучать ребенка от груди в то время, наоборот, считалось делом хорошим: дитя быстро привыкало к взрослой жизни, да и здоровьем оно отличалось богатырским.

- Сны в те дни тоже были особенные: считалось, что они сбываются до полудня, несут важный посыл или определенную информацию. Сны с невероятными предсказаниями приходят тем людям, которые испытывают трудности по жизни. Именно такие сны направляют человека по правильному пути, помогают преодолеть сомнения. О подсказке можно просить: к вечеру необходимо успокоиться, привести мысли в порядок, помолиться, поведать Богу о своей просьбе.

- Любые подсказки и знаки вселенной (голоса, необычный свет, приметы) считались проявлением предзнаменований. Нужно все запоминать, с течением некоторого времени подсказка приходила сама собой.

- Если хочется сохранить здоровье, то не надо стричься, проводить косметические процедуры или краситься.

Поговаривали даже, что в этот день легко предугадать свою судьбу. В утренние часы необходимо выглянуть в окно после сна, причем ни с кем до этого нельзя разговаривать. Кого увидят сразу, тот и станет судьбой.

Трактовка такова:

- птицы сулят новые знакомства;

- увидеть собаку – к тоске;

- кошку – к прибыли и легким деньгам;

- старик или больной человек несет проблемы со здоровьем, провал в делах;

- если за окном идет семейная пара, то можно рассчитывать на скорое замужество, примирение с любимым или пополнение в семье;

- увидеть молодого парня – к вестям о замужестве;

- молодую женщину – к счастливому году, беззаботному существованию.

Говорить об увиденном воспрещалось до того момента, как предсказание сбывалось.

По поводу гаданий у церкви однозначное мнение: это все языческие предрассудки, которые ничего хорошего не сулят. Это не приветствовалось не только в Страстную пятницу, но и ни в какой другой день. Представители церкви и сейчас продолжают утверждать, что за такие дела Господь карает людей.

Как бы это ни звучало кощунственно, но смерть на Страстную пятницу являлась делом удачным. Ведь человек верующий в пост причащается, молится, исповедуется. Он чист душой и телом. А потому к Богу он уходит с легкой душой. А если человек начинал болеть на Страстной день, то быстро выздоравливал. Не зря целители лечили и вылечивали людей, изготавливали обереги и тайные знаки в те магические и таинственные дни.

Существовало и немало примет. Вот некоторые из них:

- подул сильнейший ветер – жди дождей;

- лошадь храпит – к ненастным дням;

- сверчок запел – начинать пахоту пора;

- много шишек на ольхе – ячменя будет много;

- если на зорьке небо розовое, то погода будет ясная.

Страстная Пятница – необычный и сильный день. Нужно тихо и с уважением к Богу провести пятничный день. А свою любовь к нему нужно выражать через молитвы. Считалось, если люди придерживались особых правил, то и жизнь их в течение года была гладкой. Неплохо такие традиции перенести в современную жизнь.

Страстная пятница — особый день у православных верующих, когда мы заново переживаем страдания со Христом.

Содержание статьи

- Богослужебные особенности Страстной пятницы

- Страстная пятница. Антифон 5:

- Страстная пятница. Антифон 15:

- Страстная пятница. Прокимен, глас 4:

- Страстная пятница. Ексапостиларий:

- Страстная пятница. Стихира:

- Великая суббота:

- Видео о Страстной пятнице

- Проповеди на Страстную Пятницу

- Святитель Лука Войно-Ясенецкий о Страстной пятнице

- Митрополит Антоний Сурожский о Страстной пятнице

- Архимандрит Иоанн (Крестьянкин) о Страстной пятнице

- Прот. Валентин Амфитеатров о Страстной пятнице

- Святитель Илия Минятий о Страстной пятнице

- Митрополит Филарет (Вознесенский) о Страстной пятнице

- Литература о Страстной пятнице

- Отрывок из романа «Господа Головлевы» (М. Е. Салтыков-Щедрин) о Страстной пятнице

- Стихи о Страстной пятнице

- На Страстной (из романа «Доктор Живаго»)

- Читайте также о Страстной пятнице:

Пятница Страстной Седмицы, Страстная пятница, Великая Пятница — воспоминание Святых и Спасительных Страстей Христовых. В этот день Сам Господь принес Себя в жертву за грех мира.

О Страстях Христовых в Страстную пятницу подробно рассказывают все евангелисты, поэтому богослужения этого дня насыщены соответствующими чтениям.

Богослужебные особенности Страстной пятницы

Утреня Великой Пятницы с чтением 12 фрагментов Евангелий, посвященных Страстям Христовым, обычно совершается накануне вечером (по уставу должна совершаться в ночь с четверга на Страстную пятницу). Между Евангелиями читаются и поются стихиры и антифоны, основными мотивами которых являются предательство и сребролюбие Иуды, отпадение иудеев, величие Страстей Христовых.

По обычаю, на службе «Двенадцать Евангелий» люди стоят с зажженными свечами

В Страстную пятницу никогда (кроме совпадения с этим днем праздника Благовещения) не совершается Литургия. Вместо нее утром совершаются Царские Часы со чтением паремии (фрагмент из Ветхого Завета), Апостола и Евангелия.

В середине дня Страстной пятницы совершается вечерня с выносом плащаницы. Этой службой, посвященной положению тела Господа Иисуса Христа во гроб, заканчивается цикл богослужений Великой Пятницы.

Читайте также — Страстная пятница и псалмы невинного страдальца

Вынос Плащаницы

Тексты богослужений Страстной пятницы — шедевры византийской духовной поэзии, сопровождаются проникновенными мелодиями.

Страстная пятница. Антифон 5:

Ученик Учителя соглашаше цену, / и на тридесятих сребреницех продаде Господа, / лобзанием льстивным предая Его / беззаконником на смерть.

Ученик договаривается о цене Учителя / и за тридцать сребреников продал Господа, / коварным поцелуем предав Его / беззаконникам на смерть.

Страстная пятница. Антифон 15:

Сегодня повешен на древе Тот, Кто повесил землю на водах, венцом терновым увенчан Царь ангелов, в ложную багряницу (царскую одежду) одет Тот, Кто одевает небо облаками, получает пощечины Тот, Кто в Иордане освободил Адама, Гвоздями пригвождается Жених Церковный, копьем пробивается Сын Девы. Покланяемся Страстям Твоим, Христе. Покланяемся Страстям Твоим, Христе. Покланяемся Страстям Твоим, Христе. Покажи нам и славное Твое Воскресение.

Страстная пятница. Прокимен, глас 4:

Разделиша ризы Моя себе и о одежди Моей меташа жребий.

Стих: Боже, Боже Мой, вонми Ми, вскую оставил Мя еси?

Страстная пятница. Ексапостиларий:

Разбойника благоразумнаго во едином часе раеви сподобил еси, Господи, и мене древом крестным просвети и спаси мя.

Разбойника благоразумного сподобил рая единовременно, Господи, и меня древом крестным просвети и спаси.

Страстная пятница. Стихира:

Два и лукавная сотвори, перворожденный сын Мой Израиль: / Мене остави Источника воды животныя, / и ископа себе кладенец сокрушенный: / Мене на древе распят, / Варавву же испроси, и отпусти. / Ужасеся небо о сем, и солнце лучи скры: / ты же, Израилю, не усрамился еси, / но смерти Мя предал еси. / Остави им, Отче Святый, / не ведят бо, что сотвориша.

Два злых дела совершил / первородный сын Мой, Израиль: / он оставил Меня, Источник воды живой, / и вырыл себе колодец разбитый; / Меня распял на Древе, / а Варавву выпросил и освободил. / Изумилось при этом небо / и солнце сокрыло свои лучи. / Ты же, Израиль, не устыдился, но смерти предал Меня. / Прости им, Отче Святой, / ибо они не знают, что соделали.

Днесь висит на Древе (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы») 3.11MB

Днесь висит на древе, Иже на водах землю повесивый: венцем от терния облагается, Иже Ангелов Царь: в ложную багряницу облачается, одеваяй небо облаки: заушение прият, Иже во Иордане свободивый Адама: гвоздьми пригвоздися Жених Церковный: копием прободеся Сын Девы. Покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе: покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе: покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе, покажи нам и славное Твое Воскресение.

«Ныне висит на древе Тот, Кто повесил (утвердил) землю на водах; терновым венцом покрывается Ангелов Царь; в порфиру шутовскую одевается Одевающий небо облаками; заушения (пощечены) принимает Освободивший (от греха) Адама в Иордане; гвоздями прибивается Жених Церкви; копьем пронзается Сын Девы. Поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, покажи нам и всеславное Твое Воскресение».

_____________________________________

Не рыдай Мене, Мати (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы») 1.94MB

Не рыдай Мене, Мати, Мати, зрящи во гробе, Егоже во чреве без семени зачала еси Сына: востану бо и прославлюся, и вознесу со славою непрестанно яко Бог, верою и любовию Тя величающыя

_____________________________________

Разбойника Благоразумнаго (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы») 1.43MB

Разбойника благоразумнаго во едином часе раеви сподобил еси, Господи, и мене древом крестным просвети и спаси мя

Читайте также — Страстная пятница на иконах

_____________________________________

Великая суббота:

Благообразный Иосиф (Стихира на целование Плащаницы) Хор Валаамского

монастыря 3.73MB

«Благообразный Иосиф, с древа снем Пречистое Тело Твое, плащаницею чистою обвив, и вонями (благовониями) во гробе нове покрыв положи»Славно бо прославися (Хор свято-Ионинского монастыря) 2.89MB

_____________________________________

Воскресни, Боже (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы») 2.28MB

Воскресни, Боже, суди земли, яко Ты наследиши во всех языцех

Видео о Страстной пятнице

Проповеди на Страстную Пятницу

Святитель Лука Войно-Ясенецкий о Страстной пятнице

Свт. Лука (Войно-Ясенецкий)

Не для того нужна была жертва, чтобы умилостивился Бог, а страшная жертва принесена Христом потому, что Бог умилосердился, смилостивился над нами.

Прииди, блаженный Петр апостол, и прибавь твое святое слово к тому, что слышали мы только что от великого апостола Иоанна. — Пришел и он, и слышим мы святое слово его: «Не тленным серебром или золотом искуплены вы от суетной жизни, преданной вам от отцов, но драгоценной Кровию Христа, как непорочного и чистого Агнца» (1 Петра 1, 18-19).

Ты объяснил нам, святой Петр, от чего именно искуплены мы Кровию Христовой – от суетной жизни, которую унаследовали мы от отцов наших, от жизни в суете мирской, жизни душевной, а не духовной, в забвении величайших задач жизни нашей.

Дерзнем же теперь обратиться к Самому Господу Иисусу Христу и услышим от Него непостижимые для мира и сокровенные слова: «Я – хлеб живый, сшедший с небес; ядущий хлеб сей будет жить вовек; хлеб же, который Я дам, есть плоть Моя, которую Я отдам за жизнь мира… Истинно, истинно говорю вам: если не будете есть Плоти Сына Человеческого и пить Крови Его, то не будете иметь в себе жизни. Ядущий Мою Плоть и пиющий Мою Кровь имеет жизнь вечную, и Я воскрешу его в последний день. Ибо Плоть Моя истинно есть пища, и Кровь Моя истинно есть питие. Ядущий Мою Плоть и пиющий Мою Кровь пребывает во Мне, и Я в нем» (Ин. 6, 51, 53-56).

Вот глубочайшее и святейшее значение жертвы Христовой: Он отдал плоть Свою на умерщвление и пролил Кровь Свою для того, чтобы в великом таинстве причащения мы ели Плоть Его и пили Кровь Его; чтобы молекулы Его Тела стали молекулами плоти нашей и Кровь Его святая, вместе с нашей кровью, текла в жилах наших; чтобы таким образом стали мы причастны к Богочеловечеству и воскресил Он нас в последний день, как чад своих.

Чем же мы, убогие, воздадим Ему за безмерную любовь Его и страшную жертву Его – чем? Он Сам ответил нам на этот вопрос: «Если любите Меня, заповеди Мои соблюдите». Изольем же любовь свою и слезы свои на мертвое тело Его, лежащее пред нами на Святой Плащанице, и все силы души своей направим, прежде всего и больше всего, на соблюдение заповедей Его.

Митрополит Антоний Сурожский о Страстной пятнице

Митрополит Антоний Сурожский

Как трудно связать то, что совершается теперь, и то, что было когда-то: эту славу выноса Плащаницы и тот ужас, человеческий ужас, охвативший всю тварь: погребение Христа в ту единственную, великую неповторимую Пятницу.

Сейчас смерть Христова говорит нам о Воскресении, сейчас мы стоим с возожженными пасхальными свечами, сейчас самый Крест сияет победой и озаряет нас надеждой — но тогда было не так. Тогда на жестком, грубом деревянном кресте, после многочасового страдания, умер плотью воплотившийся Сын Божий, умер плотью Сын Девы, Кого Она любила как никого на свете — Сына Благовещения, Сына, Который был пришедший Спаситель мира.

Тогда, с того креста, ученики Распятого, которые до того были тайными, а теперь, перед лицом случившегося, открылись без страха, Иосиф и Никодим сняли тело. Было слишком поздно для похорон: тело отнесли в ближнюю пещеру в Гефсиманском саду, положили на плиту, как полагалось тогда, обвив плащаницей, закрыв лицо платом, и вход в пещеру заградили камнем — и это было как будто все.

Но вокруг этой смерти было тьмы и ужаса больше, чем мы себе можем представить. Поколебалась земля, померкло солнце, потряслось все творение от смерти Создателя. А для учеников, для женщин, которые не побоялись стоять поодаль во время распятия и умирания Спасителя, для Богородицы этот день был мрачней и страшней самой смерти.

Когда мы сейчас думаем о Великой Пятнице, мы знаем, что грядет Суббота, когда Бог почил от трудов Своих, — Суббота победы! И мы знаем, что в светозарную ночь от Субботы на Воскресный день мы будем петь Воскресение Христово и ликовать об окончательной Его победе. Но тогда пятница была последним днем. За этим днем не видно ничего, следующий день должен был быть таким, каким был предыдущий, и поэтому тьма и мрак и ужас этой Пятницы никогда никем не будут изведаны, никогда никем не будут постигнуты такими, какими они были для Девы Богородицы и для учеников Христовых.

Мы сейчас молитвенно будем слушать Плач Пресвятой Богородицы, плач Матери над телом жестокой смертью погибшего Сына. Станем слушать его. Тысячи, тысячи матерей могут узнать этот плач — и, я думаю, Ее плач страшнее всякого плача, потому что с Воскресения Христова мы знаем, что грядет победа всеобщего Воскресения, что ни един мертвый во гробе. А тогда Она хоронила не только Сына Своего, но всякую надежду на победу Божию, всякую надежду на вечную жизнь. Начиналось дление бесконечных дней, которые никогда уже больше, как тогда казалось, не могут ожить.

Вот перед чем мы стоим в образе Божией Матери, в образе учеников Христовых. Вот что значит смерть Христова. В остающееся короткое время вникнем душой в эту смерть, потому что весь этот ужас зиждется на одном: НА ГРЕХЕ, и каждый из нас, согрешающих, ответственен за эту страшную Великую Пятницу; каждый ответственен и ответит; она случилась только потому, что человек потерял любовь, оторвался от Бога. И каждый из нас, согрешающий против закона любви, ответственен за этот ужас смерти Богочеловека, сиротства Богородицы, за ужас учеников.

Поэтому, прикладываясь к священной Плащанице, будем это делать с трепетом. Он умер для тебя одного: пусть каждый это понимает! — и будем слушать этот Плач, плач всея земли, плач надежды надорванной, и благодарить Бога за спасение, которое нам дается так легко и мимо которого мы так безразлично проходим, тогда как оно далось такой страшной ценой и Спасителю-Богу, и Матери Божией, и ученикам.

Архимандрит Иоанн (Крестьянкин) о Страстной пятнице

Архимандрит Иоанн (Крестьянкин)

Длящаяся в мире жизнь Христова привела нас сегодня на Голгофу к опустевшему Кресту Божественного Страдальца, к Его гробу. А 20 столетий назад в это время вокруг Его безжизненного тела уже оставались только самые близкие, оплакивающие свою любовь и несбывшиеся надежды. Последний возглас Умирающего на Кресте «Свершишася» слышали друзья и недруги. И никто еще не понимал того дела, за которое Он умирал. Теперь же, как в капле росы отражается и играет солнце радостью жизни, так в каждой Церкви по всей земле отражаются события тех трагических и спасительных дней: вознесен Крест Господень и плащаница Христова, вещают о величайшем в истории мира свершившемся на Голгофе подвиге. На земле Спасителем и Искупителем явилось Царство Божие и зовется Оно Церковью Христовой. И сегодня уже не вместила бы Голгофа всех, принесших к прободенным стопам Спасителя свою любовь. Это Господь исполняет Свое обещание: « когда Я вознесен буду от земли, всех привлеку к Себе». (Ин.12,32). Мы то сейчас, стоя у плащаницы, уже ждем Его Воскресения. Может поэтому и не можем мы прочувствовать благодатную горечь страстей Христовых, не удержать сорокодневной радости грядущей Пасхи.

Но сегодня Великая Пятница – день великой скорби и глубоких дум. «Да молчит всяка плоть человеча и ничтоже земное в себе да помышляет». В великую Пятницу все человечество от Адама до последнего земнородного должны стоять пред плащаницей поникнув головами своими. Это их грехом смерть вошла в мир, их преступления сотворили Голгофскую казнь. Страшно сознавать себя преступником, невыносимо видеть в себе виновника смерти — убийцу. И вот это – факт! Все мы без исключения причастны к этой смерти. Нашего ради спасения смертью почил Христос Сын человеческий. Крестной смертью Сына Божия попрана смерть и милость Божия даруется людям. Смерть вещает о беспримерном деле, яже сотвори Бог – Святая Троица. Гроб, заключив в себе источник жизни, стал живоносным и несет безмолвную проповедь, и человечество призвано услышать ее, чтобы жить. Слово о любви Творца к Своему творению звучит в этой проповеди, любви к грешному и неблагодарному человеку. Вслушаемся же, дорогие , что вещает нам безмолвный Спаситель: «Для тебя, для твоего спасения Я умер. И нет больше той любви, что положила душу свою за други своя. Мысль о тебе, грешник, желание спасти тебя дало Мне силы перенести невыносимое. Ты слышал, как по-человечеству Своему, Я тужил и скорбел в саду Гефсиманском в преддверии страданий. Сердце без слов взывало к Небесному Отцу: «да мимо идет Меня чаша сия. Но воспоминание о тебе, твоей вечной гибели, сострадание и милосердие к погибающему творению Божию победили страх пред временными нечеловеческими муками. И воля Моя слилась с волей Отца Моего и любовь Его с любовью Моею к тебе, и этой силой Я осилил невыносимое. «Грехи всего мира отяготели на Мне». Твою ношу, которая для тебя непосильна Я взял на Себя».

Слова и дела любви слышим и видим мы от гроба Спасителя. Неизменна Божия Любовь и Солнце Ее светит на добрые и злые, и спасение уготовано всем пожелающим спасения. Она не престает и ныне, но всегда надеется, все переносит в ожидании нашего обращения. Но все ли мы отвечаем любовью на эту беспредельную Любовь? Не живет ли в наше время среди одних людей желание оплевать, затоптать и даже убить ее, а среди других просто забыть о ней? Господь рассеял мрак тьмы, господствующей до Его пришествия в мире, осветил путь в Царство Небесное, но и доселе враг Божий имеет свою часть в неверах, язычниках, и не знающих покаяния грешниках. Как во время служения Христа его соплеменники заменили Божии Истины ложью и превратились в лицемерных обрядоверов, так и ныне не повторяются ли и нами их заблуждения. На словах, «Господи, Господи»! а по жизни: «имей мя отречена». Не являет ли с очевидностью горький опыт жизни человечества продолжающееся его пленение богоборцу – врагу рода человеческого. Господь даровал нам радость жизни вечной, а мы предпочитаем призрачные утехи временного бытия. Христос Спаситель своим подвигом самопожертвования «лишил силы, имеющего державу смерти, то есть диавола», и смысл Его жертвы – восстановление погибающего на земле Царства Божия, похищенного врагом у прародителей наших. Но в нашей власти избирать путь мнимой свободы, по существу повиновения врагу Божию, или путь жизни следования за Христом. Благодать Божия неиссякаема в Церкви Божией.

Будем же, дорогие, жить Церковью и в Церкви, и будем помнить, что христианская жизнь есть жизнь Святого Духа. В стяжании благодати Святого Духа заключается смысл и нашей земной жизни. И сегодня, и ежегодно, в тишине Великого Пятка звучит к человечеству глас Божий: «Спасайтесь, спасайтесь, людие Мои»! Творец воссоздает Свое творение в новую благодатную жизнь, признаем же Бога своим Отцом, восчувствуем потребность в спасении и помиловании, и Господь — Источник благодати помилует и спасет нас.

Прот. Валентин Амфитеатров о Страстной пятнице

Протоиерей Валентин Амфитеатров

Таинственный, непостижимый час! Сын Божий преисполнен внутренних и внешних скорбей до последней степени, до последнего вздоха. И не бе утешаяй, и не бе скорбяй. Утеха Израиля, друг и покровитель всех угнетенных, забытых, несчастных и отверженных, всеми оставлен. Он, Спаситель, взывал к Богу Отцу: Боже Мой! Боже Мой! вскую Мя еси оставил (Мф. 27:46). Целитель сокрушенных сердец испытал боль заушения, терноношения, бичевания. Он вопиял воплем крепким, со слезами, ибо видел, что удалить страдания невозможно. Но что значит эта боль в сравнении с душевными страданиями, испытанными Иисусом Христом при виде бессердечности окружавшей Его среды? Этими печалями неисцелимо болела Божественная душа до минуты, когда предала Себя в руки Бога Отца. Предательство Иуды, сон и бегство учеников, отречение любимого, искреннейшего Петра, издевательство прислуг первосвященника, бессмысленные вопли неблагодарной черни, насмешки от Ирода, глумление от воинов, сопоставление с разбойником, неправедное осуждение, крестоношение по улицам многолюдной столицы, стыд обнажения среди самодовольно-невежественных зрителей, злорадования, брань сораспятого злодея… О, поистине возлюбленный Спаситель наш понес на Себе наказание и грехи всего мира. Только разве вечная мука может быть равной болезни неисцельной, какую испытало сердце Человеколюбца.

Начальник жизни, Чудотворец, возвращавший других к жизни, обречен на смерть. Умирает Он. Умер. За грехи наши умер!

Вечное Слово Отчее, создавшее всяческая и возвестившее миру беспредельное милосердие к грешникам, смолкло.

Солнце правды, воссиявшее миру, чтобы рассеять глубокую, мертвую мглу извращенных дел и всем явить правду Божию, светлую, яко свет… и яко полудне, зашло при непроницаемом мраке клеветы, даже с укорами в богохульстве. Страшный, непостижимый сей час! Нашим бренным очам видится один образ Божественного и живоносного тела Господа нашего Иисуса Христа, тела безмолвного и бездыханного. Он не имеет ни вида, ни славы, ни доброты, умален, отвращен, поруган.

Слушайте и смотрите! Вот Царь царствующих и Господь господствующих имеет на Своей главе венец, не драгоценными камнями украшенный, а сплетенный из терния. Кто сплел для Жизнодавца этот многоболезненный венец? Человеческая гордость, безумное тщеславие. О, если мы действительно любим своего Спасителя, то в кротости, смирении и терпении сохраним закон веры и послушания слову Его во все дни жизни нашей, пока бьется в нас жизнь сердца. Если любим нашего Христа Спасителя, если нам кажется страшным день воспоминания Великой Пятницы, страданий Иисуса, то не прибавляйте к болезненному Его терновому венцу терний своих грехов и беззаконий.

Святитель Илия Минятий о Страстной пятнице

Прискорбна есть душа Моя до смерти (Мф. 26, 38).

Свт. Илия Минятий

Человечеству пришлось увидеть на земле два великих и преславных чуда: первое, это — Бога, сошедшего на землю, чтобы принять человеческое естество; второе чудо, это — Богочеловека, восшедшего на крест, чтобы на нем умереть.

Первое явилось делом высшей премудрости и силы, второе — крайнего человеколюбия. Поэтому оба они совершились при различных обстоятельствах. В первом чуде, когда Бог принял естество человека, восторжествовала вообще вся тварь: ангелы на небесах воспели радостное славословие, пастыри на земле возликовали о спасительном благовестии и о совершившейся великой радости, и цари с востока пришли на поклонение к новорожденному Владыке с дарами.

Во втором чуде, когда Богочеловек умер на кресте, как осужденный посреди двух разбойников, тогда горний и дольний мир восплакал, небо покрылось глубочайшей тьмой, земля с основания потряслась от трепета, камни растрескались. Та ночь была светлая ночь, принесшая всемирную радость и веселье, а сей день был мрачен, как день печали и скорби. В ту ночь Бог оказал человеку благодеяние, какое только мог, а в этот день человек выказал все свое беззаконие, какое мог сделать перед Богом

Ты вправе сказать, Богочеловече и печальный Иисусе: Прискорбна есть душа Моя до смерти, — ибо многи страсти Твои, велика печаль Твоя. Страдания так велики, каких еще никогда не выносило человеческое терпение; печаль так невыносима, какой еще не испытывало человеческое сердце. И поистине, слушатели, чем более я стараюсь найти в людской жизни другой подобный пример, тем более уверяюсь в том, что Его болезнь в страстях и печаль в болезни ни с чем не сравнимы. Велика была зависть в Каине против брата, но гораздо большая зависть у архиереев и книжников против Спасителя; а неправедное убийство Авелево не сравнимо с крестной смертью Иисусовой.

Велико было терпение в Исааке, когда он готовился быть принесенным в жертву от Авраама, отца своего; но несравненно более терпения в Иисусе, Который в самом деле был предан от Отца Своего Небесного в жертву ненависти врагов Своих. Велики были злоключения Иосифа, когда он был продан братьями своими, оклеветан женой Потифара и, как виновный, был ввергнут в темницу; но гораздо многочисленнее страдания Иисусовы, когда Он продается учеником Своим, обвиняется всем сонмищем, влечется с суда на суд, как преступник. Велико было уничижение Давида, когда он свергнут был с царского престола сыном своим, когда подданные от него отступились; когда его собственные слуги гнались за ним, когда он босой убегал на гору Елеонскую, когда в него бросали камни и осыпали его ругательными словами.

Но то, что совершалось с Иисусом, когда апостолы Его покинули, воины связали, увенчали тернием, обременили крестом, когда жители всего города провожали Его поносными злохулениями, когда Он восходил на Голгофу, чтобы принять позорную смерть между двух разбойников, — все это разве не более скорбное зрелище?!

Нельзя не признать, что велика была болезнь в Иове, когда он, лишась детей своих и имений, сидел на гноище, в ранах с головы до ног; однако это должно признать только прообразом и как бы тенью тех тяжких страданий и ран, которыми был удручен многострадальный Сын Приснодевы. Не малы были страдания и после Христа пострадавших и страданиям Его подражавших святых мучеников; однако те страдания были только телесные — среди страданий душа мучеников ликовала; там была смерть, но была и честь, было мучение, но был и венец. А страсть Иисуса Христа была страданием и тела, и души, — страданием без малейшего утешения; смерть Его была одно бесчестие, мучение — одна скорбь, и скорбь смертная. Прискорбна есть душа Моя до смерти.

Митрополит Филарет (Вознесенский)

Митрополит Филарет (Вознесенский) о Страстной пятнице

Помните, возлюбленные: когда мы с вами размышляем о том, что Господь сделал для нас, то никогда не следует забывать, что вот именно ради наших грехов Он оказался во гробе. На Кресте и во гробе. Мы Его пригвоздили своими упорными и нераскаянными грехами ко Кресту, и из-за наших грехов Он теперь возлежит, безгласный и недвижимый, мертвецом во гробе. И когда будешь поклоняться Ему, лобызать Его Язвы, делай это как безответно виновный, в том, что вот Он изъязвлен, в том, что Он изранен, в том, что Он измучен, оплеван, позором покрыт и теперь — лежит в гробе.

Помни, что мы это сделали: и я, и всякий другой своими упорными грехами и своей неисправленностью. Не даром же сам Господь когда-то, когда почувствовал как-то очень болезненно неверность человеческого рода, воскликнул даже (в Евангелии это записано): «О род неверный и развращенный, доколе Я буду с вами, доколе Я буду терпеть вас!»**** Вот как Ему было вообще тяжко с нами, а тут мы, повторяю, своими грехами пригвоздили ко Кресту и положили во гроб.

Так и помни, душа христианская, когда будешь поклоняться Божественному Мертвецу в Плащанице лежащему, когда будешь лобызать Его Язвы, как безответно виновный это делай, потому что никто кроме нас не виноват в том, что Господь Иисус Христос, как говорил Апостол, вместо предлежащей Ему славы перенес эту срамоту и позор, и эту страшную, позорную и унизительную крестную смерть. Мы с вами знаем, что теперь, после Его смерти, Крест стал нашей драгоценностью и святыней, но пригвоздили ко Кресту Его, повторяю, не воины, а — мы с вами, потому что если бы наших грехов не было на Нем, не было бы Ему что взять на Себя, тогда бы не было ничего этого. Но Он — пошел на этот страшный сверхчеловеческий Подвиг. Помните, как в Евангелии сказано, что Он до пота кровавого боролся в Гефсиманском саду, на этой страшной молитве.

Почему он был покрыт кровавым страшным потом? Когда-то святитель Димитрий Ростовский в своей вдохновенной проповеди говорил, как бы обращаясь к Спасителю: » Господи! Почему Ты покрыт кровью? Кто Тебя изранил? Не было ни Креста, ни бичевания, — ничего этого еще не было; почему Ты весь в крови?» И сам же отвечает: «Кто изранил? — Любовь изранила!» Потому что знал Богочеловек, столько возлюбивший нас, грешных, что если Он не совершит этого страшного Подвига, то наша участь, навеки! — в геенне огненной, в страшных, нескончаемых и ужаснейших мучениях, которых мы себе и представить не можем. А вот, Он взял на Себя всю эту страшную тяжесть, это тяжкое бремя греховное, и, благодаря Его святому и великому Подвигу, мы имеем возможность уповать на то, что получим прощение наших грехов, именно Им омытых. И тогда можем мы надеяться, что и нас примет Он в Царствие Небесное, так, как Он принял Благоразумного разбойника.

Литература о Страстной пятнице

Отрывок из романа «Господа Головлевы» (М. Е. Салтыков-Щедрин) о Страстной пятнице

М. Е. Салтыков-Щедрин

Иудушка и Аннинька сидели вдвоем в столовой. Не далее как час тому назад кончилась всенощная, сопровождаемая чтением двенадцати Евангелий, и в комнате еще слышался сильный запах ладана. Часы пробили десять, домашние разошлись по углам, и в доме водворилось глубокое, сосредоточенное молчание. Аннинька, взявши голову в обе руки, облокотилась на стол и задумалась; Порфирий Владимирыч сидел напротив, молчаливый и печальный.

На Анниньку эта служба всегда производила глубоко потрясающее впечатление. Еще будучи ребенком, она горько плакала, когда батюшка произносил: «И сплетше венец из терния, возложиша на главу Его, и трость в десницу Его», — и всхлипывающим дискантиком подпевала дьячку: «Слава долготерпению Твоему, Господи! слава Тебе!» А после всенощной, вся взволнованная, прибегала в девичью и там, среди сгустившихся сумерек (Арина Петровна не давала в девичью свечей, когда не было работы), рассказывала рабыням «Страсти Господни».

Лились тихие рабьи слезы, слышались глубокие рабьи воздыхания. Рабыни чуяли сердцами своего Господина и Искупителя, верили, что Он воскреснет, воистину воскреснет. И Аннинька тоже чуяла и верила. За глубокой ночью истязаний, подлых издевок и покиваний, для всех этих нищих духом виднелось царство лучей и свободы. Сама старая барыня, Арина Петровна, обыкновенно грозная, делалась в эти дни тихою, не брюзжала, не попрекала Анниньку сиротством, а гладила ее по головке и уговаривала не волноваться. Но Аннинька даже в постели долго не могла успокоиться, вздрагивала, металась, по нескольку раз в течение ночи вскакивала и разговаривала сама с собой.

Потом наступили годы учения, а затем и годы странствования. Первые были бессодержательны, вторые — мучительно пошлы. Но и тут, среди безобразий актерского кочевья, Аннинька ревниво выделяла «святые дни» и отыскивала в душе отголоски прошлого, которые помогали ей по-детски умиляться и вздыхать.

Теперь же, когда жизнь выяснилась вся, до последней подробности, когда прошлое проклялось само собою, а в будущем не предвиделось ни раскаяния, ни прощения, когда иссяк источник умиления, а вместе с ним иссякли и слезы, — впечатление, произведенное только что выслушанным сказанием о скорбном пути, было поистине подавляющим. И тогда, в детстве, над нею тяготела глубокая ночь, но за тьмою все-таки предчувствовались лучи. Теперь — ничего не предчувствовалось, ничего не предвиделось: ночь, вечная, бессменная ночь — и ничего больше. Аннинька не вздыхала, не волновалась и, кажется, даже ни о чем не думала, а только впала в глубокое оцепенение.

С своей стороны, и Порфирий Владимирыч, с не меньшею аккуратностью, с молодых ногтей чтил «святые дни», но чтил исключительно с обрядной стороны, как истый идолопоклонник. Каждогодно, накануне великой пятницы, он приглашал батюшку, выслушивал евангельское сказание, вздыхал, воздевал руки, стукался лбом в землю, отмечал на свече восковыми катышками число прочитанных евангелий и все-таки ровно ничего не понимал. И только теперь, когда Аннинька разбудила в нем сознание «умертвий», он понял впервые, что в этом сказании идет речь о какой-то неслыханной неправде, совершившей кровавый суд над Истиной…

Конечно, было бы преувеличением сказать, что по поводу этого открытия в душе его возникли какие-либо жизненные сопоставления, но несомненно, что в ней произошла какая-то смута, почти граничащая с отчаянием. Эта смута была тем мучительнее, чем бессознательнее прожилось то прошлое, которое послужило ей источником. Было что-то страшное в этом прошлом, а что именно — в массе невозможно припомнить. Но и позабыть нельзя. Что-то громадное, которое до сих пор неподвижно стояло, прикрытое непроницаемою завесою, и только теперь двинулось навстречу, каждоминутно угрожая раздавить.

Если б еще оно взаправду раздавило — это было бы самое лучшее; но ведь он живуч — пожалуй, и выползет. Нет, ждать развязки от естественного хода вещей — слишком гадательно; надо самому создать развязку, чтобы покончить с непосильною смутою. Есть такая развязка, есть. Он уже с месяц приглядывается к ней, и теперь, кажется, не проминет. «В субботу приобщаться будем — надо на могилку к покойной маменьке проститься сходить!» — вдруг мелькнуло у него в голове.

— Сходим, что ли? — обратился он к Анниньке, сообщая ей вслух о своем предположении.

— Пожалуй… съездимте…

— Нет, не съездимте, а… — начал было Порфирий Владимирыч и вдруг оборвал, словно сообразил, что Аннинька может помешать.

«А ведь я перед покойницей маменькой… ведь я ее замучил… я!» — бродило между тем в его мыслях, и жажда «проститься» с каждой минутой сильнее и сильнее разгоралась в его сердце. Но «проститься» не так, как обыкновенно прощаются, а пасть на могилу и застыть в воплях смертельной агонии.

— Так ты говоришь, что Любинька сама от себя умерла? — вдруг спросил он, видимо, с целью подбодрить себя.

Сначала Аннинька словно не расслышала вопроса дяди, но, очевидно, он дошел до нее, потому что через две-три минуты она сама ощутила непреодолимую потребность возвратиться к этой смерти, измучить себя ею.

— Так и сказала: пей… подлая?! — переспросил он, когда она подробно повторила свой рассказ.

— Да… сказала.

— А ты осталась? не выпила?

— Да… вот живу…

Он встал и несколько раз в видимом волнении прошелся взад и вперед по комнате. Наконец подошел к Анниньке и погладил ее по голове.

— Бедная ты! бедная ты моя! — произнес он тихо.

При этом прикосновении в ней произошло что-то неожиданное. Сначала она изумилась. но постепенно лицо ее начало искажаться, искажаться, и вдруг целый поток истерических, ужасных рыданий вырвался из ее груди.

— Дядя! вы добрый? скажите, вы добрый? — почти криком кричала она.

Прерывающимся голосом, среди слез и рыданий, твердила она свой вопрос, тот самый, который она предложила еще в тот день, когда после «странствия» окончательно воротилась для водворения в Головлеве, и на который он в то время дал такой нелепый ответ.

— Вы добрый? скажите! ответьте! вы добрый?

— Слышала ты, что за всенощной сегодня читали? — спросил он, когда она, наконец, затихла, — ах, какие это были страдания! Ведь только этакими страданиями и можно… И простил! всех навсегда простил!

Он опять начал большими шагами ходить по комнате, убиваясь, страдая и не чувствуя, как лицо его покрывается каплями пота.

— Всех простил! — вслух говорил он сам с собою, — не только тех, которые тогда напоили его оцтом с желчью, но и тех, которые и после, вот теперь, и впредь, во веки веков будут подносить к Его губам оцет, смешанный с желчью… Ужасно! ах, это ужасно!

И вдруг, остановившись перед ней, спросил:

— А ты… простила?

Вместо ответа она бросилась к нему и крепко его обняла.

— Надо меня простить! — продолжал он, — за всех… И за себя… и за тех, которых уж нет… Что такое! что такое сделалось?! — почти растерянно восклицал он, озираясь кругом, — где… все?..

Стихи о Страстной пятнице

На Страстной (из романа «Доктор Живаго»)

Б. Л. Пастернак

Б. Л. Пастернак

Еще кругом ночная мгла.

Еще так рано в мире,

Что звездам в небе нет числа,

И каждая, как день, светла,

И если бы земля могла,

Она бы Пасху проспала

Под чтение Псалтыри.

Еще кругом ночная мгла.

Такая рань на свете,

Что площадь вечностью легла

От перекрестка до угла,

И до рассвета и тепла

Еще тысячелетье.

Еще земля голым-гола,

И ей ночами не в чем

Раскачивать колокола

И вторить с воли певчим.

И со Страстного четверга

Вплоть до Страстной субботы

Вода буравит берега

И вьет водовороты.

И лес раздет и непокрыт,

И на Страстях Христовых,

Как строй молящихся, стоит

Толпой стволов сосновых.

А в городе, на небольшом

Пространстве, как на сходке,

Деревья смотрят нагишом

В церковные решетки.

И взгляд их ужасом объят.

Понятна их тревога.

Сады выходят из оград,

Колеблется земли уклад:

Они хоронят Бога.

И видят свет у царских врат,

И черный плат, и свечек ряд,

Заплаканные лица —

И вдруг навстречу крестный ход

Выходит с плащаницей,

И две березы у ворот

Должны посторониться.

И шествие обходит двор

По краю тротуара,

И вносит с улицы в притвор

Весну, весенний разговор

И воздух с привкусом просфор

И вешнего угара.

И март разбрасывает снег

На паперти толпе калек,

Как будто вышел Человек,

И вынес, и открыл ковчег,

И все до нитки роздал.

И пенье длится до зари,

И, нарыдавшись вдосталь,

Доходят тише изнутри

На пустыри под фонари

Псалтирь или Апостол.

Но в полночь смолкнут тварь и плоть,

Заслышав слух весенний,

Что только-только распогодь,

Смерть можно будет побороть

Усильем Воскресенья.

1946

Читайте также о Страстной пятнице:

- Страстная пятница

- Страстная — стать соучастником Спасителю

- Страстная

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

Страстная пятница — день скорби и поминовения для всех верующих, ведь именно в это день был распят Иисус Христос. В 2022 году Великая пятница выпадает на 22 апреля. Этот праздник традиционно отмечают в последнюю пятницу перед Пасхой. Что можно и нельзя делать в этот день? Какую пищу едят верующие в предпоследний день Великого поста?

Суть Страстной пятницы и события в Евангелии

Страстная пятница – это день, когда распятый на кресте Сын Божий умер в страшных мучениях. Понтий Пилат, который вынес смертный приговор, на самом деле не хотел казнить Иисуса, но под напором вынужден был идти на поводу у толпы.

Преданный своим учеником Иудой Искариотом Спаситель воскликнул перед смертью: «Отче! Прости им, ибо не знают, что делают». Когда Христос скончался, день превратился в ночь, а камни под крестом раскололись. Тогда люди уверовали в Иисуса.

В Страстную пятницу православные вспоминают поступок Сына Божьего. В храмах проходят богослужения. Верующие в благодарность Христу готовы разделить его муки, отказавшись от естественных потребностей.

Фото: © ТАСС/Михаил Терещенко

Что можно делать в Страстную пятницу

Так как в Страстную пятницу существуют многочисленные запреты для верующих, этот день рекомендуется посвятить молитвам, чтению Евангелия, размышлениям о своих грехах, покаянию и походу в церковь.

Во время службы зажигается 12 свечей. Их нужно отнести домой и зажечь во всех комнатах. Считается, что это привлекает благополучие и улучшает атмосферу.

В Великую пятницу стоит:

- принять участие в выносе Плащаницы;

- помолиться;

- посетить храм;

- ограничить себя в пище;

- сходить на исповедь.

Что нельзя делать в Страстную пятницу

Для верующих в Страстную пятницу действует ряд запретов. В этот день им не рекомендуется:

- развлекаться и устраивать шумные застолья;

- принимать пищу до выноса Плащаницы в 15:00;

- делать уборку;

- выполнять сельскохозяйственные работы;

- праздновать дни рождения, свадьбы или проводить другие мероприятия.

Фото: © ТАСС/Владимир Смирнов

Служба в Великую пятницу

Во время богослужений в Страстную пятницу повествуется о муках Христа на кресте, его смерти и погребении. На утрене читают по очереди 12 евангельских отрывков в хронологическом порядке, которые рассказывают о событиях Великой пятницы.

На Великих часах отдельно читают о случившемся от каждого из четырех евангелистов. Во время вечерни о событиях Страстной пятницы повествуют в одном продолжительном составном Евангелии.

Литургия в праздник не проводится. Исключение — когда Благовещение совпадает со Страстной пятницей. В таком случае совершают литургию Иоанна Златоуста.

Вынос Плащаницы

На вечерне выносят Плащаницу из алтаря, размещают ее в середине храма и поют особый канон «О распятии Господа». Плащаница располагается в центре храма три неполных дня.

Она напоминает верующим трехдневное нахождение Иисуса Христа во гробе. Это действие включили в вечерню только в конце XVI века, а сейчас оно является обязательным.

Фото: © ТАСС/Михаил Терещенко

Молитвы и библейские тексты в Страстную пятницу

Определенных правил о том, какие молитвы нужно читать в Страстную пятницу, нет. Верующие читают Священное Писание и выбирают те молитвы, которые откликаются в их сердце и отражают душевное состояние.

Акцентировать внимание стоит на тех молитвах и местах в Библии, которые посвящены последним дням жизни Спасителя.

Пост в Страстную пятницу

Пятница является самым строгим днем Страстной недели Великого поста. Верующим стоит воздержаться от любой пищи до выноса в храмах Туринской плащаницы. То есть с утра и до 15:00 нужно полностью отказаться от еды. После этого разрешается употреблять только воду и постный хлеб. Но согласно календарю питания также позволяется есть сырые овощи и фрукты.

Есть и пить в Великую пятницу можно следующие продукты:

- чай на травах (без сахара);

- фрукты и овощи (в сыром, консервированном и моченом виде);

- натуральный сок из любых фруктов и овощей;

- сухофрукты и орехи.

Такое воздержание от пищи может позволить себе только здоровый и подготовленный человек.

| Good Friday | |

|---|---|

A Stabat Mater depiction, 1868 |

|

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Commemoration of the crucifixion and the death of Jesus Christ |

| Celebrations | Celebration of the Passion of the Lord |

| Observances | Worship services, prayer and vigil services, fasting, almsgiving |

| Date | The Friday immediately preceding Easter Sunday |

| 2022 date |

|

| 2023 date |

|

| 2024 date |

|

| 2025 date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Passover, Christmas (which celebrates the birth of Jesus), Septuagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter, Easter Sunday (primarily), Divine Mercy Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Whit Monday, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi and Feast of the Sacred Heart which follow it. It is related to the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which focuses on the benefits, graces, and merits of the Cross, rather than Jesus’s death. |

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Holy and Great Friday), and Black Friday.[2][3][4]

Members of many Christian denominations, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist, Oriental Orthodox, United Protestant and some Reformed traditions (including certain Continental Reformed, Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches), observe Good Friday with fasting and church services.[5][6][7] In many Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist churches, the Service of the Great Three Hours’ Agony is held from noon until 3 pm, the time duration that the Bible records as darkness covering the land to Jesus’ sacrificial death on the cross.[8] Communicants of the Moravian Church have a Good Friday tradition of cleaning gravestones in Moravian cemeteries.[9]

The date of Good Friday varies from one year to the next in both the Gregorian and Julian calendars. Eastern and Western Christianity disagree over the computation of the date of Easter and therefore of Good Friday. Good Friday is a widely instituted legal holiday around the world, including in most Western countries and 12 U.S. states.[10] Some predominantly Christian countries, such as Germany, have laws prohibiting certain acts such as dancing and horse racing, in remembrance of the somber nature of Good Friday.[11][12]

Etymology[edit]

‘Good Friday’ comes from the sense ‘pious, holy’ of the word «good».[13] Less common examples of expressions based on this obsolete sense of «good» include «the good book» for the Bible, «good tide» for «Christmas» or Shrovetide, and Good Wednesday for the Wednesday in Holy Week.[14] A common folk etymology incorrectly analyzes «Good Friday» as a corruption of «God Friday» similar to the linguistically correct description of «goodbye» as a contraction of «God be with you». In Old English, the day was called «Long Friday» (langa frigedæg [ˈlɑŋɡɑ ˈfriːjedæj]), and equivalents of this term are still used in Scandinavian languages and Finnish.[15]

Other languages[edit]

In Latin, the name used by the Catholic Church until 1955 was Feria sexta in Parasceve («Friday of Preparation [for the Sabbath]»). In the 1955 reform of Holy Week, it was renamed Feria sexta in Passione et Morte Domini («Friday of the Passion and Death of the Lord»), and in the new rite introduced in 1970, shortened to Feria sexta in Passione Domini («Friday of the Passion of the Lord»).

In Dutch, Good Friday is known as Goede Vrijdag, in Frisian as Goedfreed. In German-speaking countries, it is generally referred to as Karfreitag («Mourning Friday», with Kar from Old High German kara‚ «bewail», «grieve»‚ «mourn», which is related to the English word «care» in the sense of cares and woes), but it is sometimes also called Stiller Freitag («Silent Friday») and Hoher Freitag («High Friday, Holy Friday»). In the Scandinavian languages and Finnish («pitkäperjantai»), it is called the equivalent of «Long Friday» as it was in Old English («Langa frigedæg»).

In Irish it is known as Aoine an Chéasta, «Friday of Crucifixion», from céas, «suffer;»[16] similarly, it is DihAoine na Ceusta in Scottish Gaelic.[17] In Welsh it is called Dydd Gwener y Groglith, «Friday of the Cross-Reading», referring to Y Groglith, a medieval Welsh text on the Crucifixion of Jesus that was traditionally read on Good Friday.[18]

In Greek, Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Breton and Armenian it is generally referred to as the equivalent of «Great Friday» (Μεγάλη Παρασκευή, Wielki Piątek, Nagypéntek, Vinerea Mare, Gwener ar Groaz, Ավագ Ուրբաթ). In Serbian, it is referred either Велики петак («Great Friday»), or, more commonly, Страсни петак («Loved Friday»). In Bulgarian, it is called either Велики петък («Great Friday»), or, more commonly, Разпети петък («Crucified Friday»). In French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese it is referred to as Vendredi saint, Venerdì santo, Viernes Santo and Sexta-Feira Santa («Holy Friday»), respectively. In Arabic, it is known as «الجمعة العظيمة» («Great Friday»). In Malayalam, it is called ദുഃഖ വെള്ളി («Sad Friday»).

Biblical accounts[edit]

According to the accounts in the Gospels, the royal soldiers, guided by Jesus’ disciple Judas Iscariot, arrested Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Judas received money (30 pieces of silver) [19] for betraying Jesus and told the guards that whomever he kisses is the one they are to arrest. Following his arrest, Jesus was taken to the house of Annas, the father-in-law of the high priest, Caiaphas. There he was interrogated with little result and sent bound to Caiaphas the high priest where the Sanhedrin had assembled.[20]

Conflicting testimony against Jesus was brought forth by many witnesses, to which Jesus answered nothing. Finally the high priest adjured Jesus to respond under solemn oath, saying «I adjure you, by the Living God, to tell us, are you the Anointed One, the Son of God?» Jesus testified ambiguously, «You have said it, and in time you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Almighty, coming on the clouds of Heaven.» The high priest condemned Jesus for blasphemy, and the Sanhedrin concurred with a sentence of death.[21] Peter, waiting in the courtyard, also denied Jesus three times to bystanders while the interrogations were proceeding just as Jesus had foretold.

In the morning, the whole assembly brought Jesus to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate under charges of subverting the nation, opposing taxes to Caesar, and making himself a king.[22] Pilate authorized the Jewish leaders to judge Jesus according to their own law and execute sentencing; however, the Jewish leaders replied that they were not allowed by the Romans to carry out a sentence of death.[23]

Pilate questioned Jesus and told the assembly that there was no basis for sentencing. Upon learning that Jesus was from Galilee, Pilate referred the case to the ruler of Galilee, King Herod, who was in Jerusalem for the Passover Feast. Herod questioned Jesus but received no answer; Herod sent Jesus back to Pilate. Pilate told the assembly that neither he nor Herod found Jesus to be guilty; Pilate resolved to have Jesus whipped and released.[24] Under the guidance of the chief priests, the crowd asked for Barabbas, who had been imprisoned for committing murder during an insurrection. Pilate asked what they would have him do with Jesus, and they demanded, «Crucify him»[25] Pilate’s wife had seen Jesus in a dream earlier that day, and she forewarned Pilate to «have nothing to do with this righteous man».[26] Pilate had Jesus flogged and then brought him out to the crowd to release him. The chief priests informed Pilate of a new charge, demanding Jesus be sentenced to death «because he claimed to be God’s son.» This possibility filled Pilate with fear, and he brought Jesus back inside the palace and demanded to know from where he came.[27]

Coming before the crowd one last time, Pilate declared Jesus innocent and washed his own hands in water to show he had no part in this condemnation. Nevertheless, Pilate handed Jesus over to be crucified in order to forestall a riot.[28] The sentence written was «Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.» Jesus carried his cross to the site of execution (assisted by Simon of Cyrene), called the «place of the Skull», or «Golgotha» in Hebrew and in Latin «Calvary». There he was crucified along with two criminals.[29]

Jesus agonized on the cross for six hours. During his last three hours on the cross, from noon to 3 pm, darkness fell over the whole land.[30] Jesus spoke from the cross, quoting the messianic Psalm 22: «My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?»

With a loud cry, Jesus gave up his spirit. There was an earthquake, tombs broke open, and the curtain in the Temple was torn from top to bottom. The centurion on guard at the site of crucifixion declared, «Truly this was God’s Son!»[31]

Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin and a secret follower of Jesus, who had not consented to his condemnation, went to Pilate to request the body of Jesus[32] Another secret follower of Jesus and member of the Sanhedrin named Nicodemus brought about a hundred-pound weight mixture of spices and helped wrap the body of Jesus.[33] Pilate asked confirmation from the centurion of whether Jesus was dead.[34] A soldier pierced the side of Jesus with a lance causing blood and water to flow out[35] and the centurion informed Pilate that Jesus was dead.[36]

Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus’ body, wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and placed it in his own new tomb that had been carved in the rock[37] in a garden near the site of the crucifixion. Nicodemus[38] also brought 75 pounds of myrrh and aloes, and placed them in the linen with the body, in keeping with Jewish burial customs[33] They rolled a large rock over the entrance of the tomb.[39] Then they returned home and rested, because Shabbat had begun at sunset.[40] Matt. 28:1 «After the Shabbat, at dawn on the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to look at the tomb». i.e. «After the Sabbath, at dawn on the first day of the week,…». «He is not here; he has risen, just as he said….». (Matt. 28:6)

Orthodox[edit]

Byzantine Christians (Eastern Christians who follow the Rite of Constantinople: Orthodox Christians and Greek-Catholics) call this day «Great and Holy Friday», or simply «Great Friday».[41] Because the sacrifice of Jesus through his crucifixion is recalled on this day, the Divine Liturgy (the sacrifice of bread and wine) is never celebrated on Great Friday, except when this day coincides with the Great Feast of the Annunciation, which falls on the fixed date of 25 March (for those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, 25 March currently falls on 7 April of the modern Gregorian Calendar). Also on Great Friday, the clergy no longer wear the purple or red that is customary throughout Great Lent,[42] but instead don black vestments. There is no «stripping of the altar» on Holy and Great Thursday as in the West; instead, all of the church hangings are changed to black, and will remain so until the Divine Liturgy on Great Saturday.

The faithful revisit the events of the day through the public reading of specific Psalms and the Gospels, and singing hymns about Christ’s death. Rich visual imagery and symbolism, as well as stirring hymnody, are remarkable elements of these observances. In the Orthodox understanding, the events of Holy Week are not simply an annual commemoration of past events, but the faithful actually participate in the death and the resurrection of Jesus.

Each hour of this day is the new suffering and the new effort of the expiatory suffering of the Savior. And the echo of this suffering is already heard in every word of our worship service – unique and incomparable both in the power of tenderness and feeling and in the depth of the boundless compassion for the suffering of the Savior. The Holy Church opens before the eyes of believers a full picture of the redeeming suffering of the Lord beginning with the bloody sweat in the Garden of Gethsemane up to the crucifixion on Golgotha. Taking us back through the past centuries in thought, the Holy Church brings us to the foot of the cross of Christ erected on Golgotha and makes us present among the quivering spectators of all the torture of the Savior.[43]

Great and Holy Friday is observed as a strict fast, also called the Black Fast, and adult Byzantine Christians are expected to abstain from all food and drink the entire day to the extent that their health permits. «On this Holy day neither a meal is offered nor do we eat on this day of the crucifixion. If someone is unable or has become very old [or is] unable to fast, he may be given bread and water after sunset. In this way we come to the holy commandment of the Holy Apostles not to eat on Great Friday.»[43]

Matins of Holy and Great Friday[edit]

The Byzantine Christian observance of Holy and Great Friday, which is formally known as The Order of Holy and Saving Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ, begins on Thursday night with the Matins of the Twelve Passion Gospels. Scattered throughout this Matins service are twelve readings from all four of the Gospels which recount the events of the Passion from the Last Supper through the Crucifixion and burial of Jesus. Some churches have a candelabrum with twelve candles on it, and after each Gospel reading one of the candles is extinguished.[44]

The first of these twelve readings[45] is the longest Gospel reading of the liturgical year, and is a concatenation from all four Gospels. Just before the sixth Gospel reading, which recounts Jesus being nailed to the cross, a large cross is carried out of the sanctuary by the priest, accompanied by incense and candles, and is placed in the center of the nave (where the congregation gathers) Sēmeron Kremātai Epí Xýlou:

Today He who hung the earth upon the waters is hung upon the Cross (three times).

He who is King of the angels is arrayed in a crown of thorns.

He who wraps the Heavens in clouds is wrapped in the purple of mockery.

He who in Jordan set Adam free receives blows upon His face.

The Bridegroom of the Church is transfixed with nails.

The Son of the Virgin is pierced with a spear.

We venerate Thy Passion, O Christ (three times).

Show us also Thy glorious Resurrection.[46][47]

The readings are:

- John 13:31-18:1 – Christ’s last sermon, Jesus prays for the apostles.

- John 18:1–28 – The agony in the garden, the mockery and denial of Christ.

- Matthew 26:57–75 – The mockery of Christ, Peter denies Christ.

- John 18:28–19:16 – Pilate questions Jesus; Jesus is condemned; Jesus is mocked by the Romans.

- Matthew 27:3–32 – Judas commits suicide; Jesus is condemned; Jesus mocked by the Romans; Simon of Cyrene compelled to carry the cross.

- Mark 15:16–32 – Jesus dies.

- Matthew 27:33–54 – Jesus dies.

- Luke 23:32–49 – Jesus dies.

- John 19:25–37 – Jesus dies.

- Mark 15:43–47 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- John 19:38–42 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- Matthew 27:62–66 – The Jews set a guard.

During the service, all come forward to kiss the feet of Christ on the cross. After the Canon, a brief, moving hymn, The Wise Thief is chanted by singers who stand at the foot of the cross in the center of the nave. The service does not end with the First Hour, as usual, but with a special dismissal by the priest:

May Christ our true God, Who for the salvation of the world endured spitting, and scourging, and buffeting, and the Cross, and death, through the intercessions of His most pure Mother, of our holy and God-bearing fathers, and of all the saints, have mercy on us and save us, for He is good and the Lover of mankind.

Royal Hours[edit]

Vigil during the Service of the Royal Hours

The next day, in the forenoon on Friday, all gather again to pray the Royal Hours,[48] a special expanded celebration of the Little Hours (including the First Hour, Third Hour, Sixth Hour, Ninth Hour and Typica) with the addition of scripture readings (Old Testament, Epistle and Gospel) and hymns about the Crucifixion at each of the Hours (some of the material from the previous night is repeated). This is somewhat more festive in character, and derives its name of «Royal» from both the fact that the Hours are served with more solemnity than normal, commemorating Christ the King who humbled himself for the salvation of mankind, and also from the fact that this service was in the past attended by the Emperor and his court.[49]

Vespers of Holy and Great Friday[edit]

In the afternoon, around 3 pm, all gather for the Vespers of the Taking-Down from the Cross,[50] commemorating the Deposition from the Cross. Following Psalm 103 (104) and the Great Litany, ‘Lord, I call’ is sung without a Psalter reading. The first five stichera (the first being repeated) are taken from the Aposticha at Matins the night before, but the final 3 of the 5 are sung in Tone 2. Three more stichera in Tone 6 lead to the Entrance. The Evening Prokimenon is taken from Psalm 21 (22): ‘They parted My garments among them, and cast lots upon My vesture.’

There are then four readings, with Prokimena before the second and fourth:

- Exodus 33:11-23 — God shows Moses His glory

- The second Prokimenon is from Psalm 34 (35): ‘Judge them, O Lord, that wrong Me: fight against them that fight against Me.’

- Job 42:12-20 — God restores Job’s wealth (note that verses 18-20 are found only in the Septuagint)

- Isaiah 52:13-54:1 — The fourth Suffering Servant song

- The third Prokimenon is from Psalm 87 (88): ‘They laid Me in the lowest pit: in dark places and in the shadow of death.’

- 1 Corinthians 1:18-2:2 — St. Paul places Christ crucified as the centre of the Christian life

An Alleluia is then sung, with verses from Psalm 68 (69): ‘Save Me, O God: for the waters are come in, even unto My soul.’

The Gospel reading is a composite taken from three of the four the Gospels (Matthew 27:1-38; Luke 23:39-43; Matthew 27:39-54; John 19:31-37; Matthew 27:55-61), essentially the story of the Crucifixion as it appears according to St. Matthew, interspersed with St. Luke’s account of the confession of the Good Thief and St. John’s account of blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side. During the Gospel, the body of Christ (the soma) is removed from the cross, and, as the words in the Gospel reading mention Joseph of Arimathea, is wrapped in a linen shroud, and taken to the altar in the sanctuary.

The epitaphios («winding sheet»), depicting the preparation of the body of Jesus for burial

The Aposticha reflects on the burial of Christ. Either at this point (in the Greek use) or during the troparion following (in the Slav use):

Noble Joseph, taking down Thy most pure body from the Tree, wrapped it in pure linen and spices, and he laid it in a new tomb.[51]

an epitaphios or «winding sheet» (a cloth embroidered with the image of Christ prepared for burial) is carried in procession to a low table in the nave which represents the Tomb of Christ; it is often decorated with an abundance of flowers. The epitaphios itself represents the body of Jesus wrapped in a burial shroud, and is a roughly full-size cloth icon of the body of Christ. The service ends with a hope of the Resurrection:

The Angel stood by the tomb, and to the women bearing spices he cried aloud: ‘Myrrh is fitting for the dead, but Christ has shown Himself a stranger to corruption.[51]

Then the priest may deliver a homily and everyone comes forward to venerate the epitaphios. In the Slavic practice, at the end of Vespers, Compline is immediately served, featuring a special Canon of the Crucifixion of our Lord and the Lamentation of the Most Holy Theotokos by Symeon the Logothete.[52]

Matins of Holy and Great Saturday[edit]

The Epitaphios being carried in procession in a church in Greece.

On Friday night, the Matins of Holy and Great Saturday, a unique service known as The Lamentation at the Tomb[53] (Epitáphios Thrēnos) is celebrated. This service is also sometimes called Jerusalem Matins. Much of the service takes place around the tomb of Christ in the center of the nave.[54]

Epitaphios adorned for veneration, Church of Saints Constantine and Helen, Hippodromion Sq., Thessaloniki, Greece (Good Friday 2022).

A unique feature of the service is the chanting of the Lamentations or Praises (Enkōmia), which consist of verses chanted by the clergy interspersed between the verses of Psalm 119 (which is, by far, the longest psalm in the Bible). The Enkōmia are the best-loved hymns of Byzantine hymnography, both their poetry and their music being uniquely suited to each other and to the spirit of the day. They consist of 185 tercet antiphons arranged in three parts (stáseis or «stops»), which are interjected with the verses of Psalm 119, and nine short doxastiká («Gloriae») and Theotókia (invocations to the Virgin Mary). The three stáseis are each set to its own music, and are commonly known by their initial antiphons: Ἡ ζωὴ ἐν τάφῳ, «Life in a grave», Ἄξιον ἐστί, «Worthy it is», and Αἱ γενεαὶ πᾶσαι, «All the generations». Musically they can be classified as strophic, with 75, 62, and 48 tercet stanzas each, respectively. The climax of the Enkōmia comes during the third stásis, with the antiphon «Ō glyký mou Éar«, a lamentation of the Virgin for her dead Child («O, my sweet spring, my sweetest child, where has your beauty gone?»). Later, during a different antiphon of that stasis («Early in the morning the myrrh-bearers came to Thee and sprinkled myrrh upon Thy tomb»), young girls of the parish place flowers on the Epitaphios and the priest sprinkles it with rose-water. The author(s) and date of the Enkōmia are unknown. Their High Attic linguistic style suggests a dating around the 6th century, possibly before the time of St. Romanos the Melodist.[55]

The Epitaphios mounted upon return of procession, at an Orthodox Church in Adelaide, Australia.