Русская Православная Церковь

-

23 Декабрь 2022

26 декабря, в понедельник, в 19.00 в Лектории на Воробьевых горах храма Троицы и МГУ, к 100-летию СССР состоится выступление Михаил а Борисович а С МОЛИНА , историк а русской консервативной мысли, кандидат а исторических наук, директор а Фонда «Имперское возрождение» , по теме «Учреждение СССР — уничтож ение историческ ой Росси и » .

Адрес: Косыгина, 30.

Проезд: от м.Октябрьская, Ленинский проспект, Ломоносовский проспект, Киевская маршрут№297 до ост. Смотровая площадка. -

28 Ноябрь 2022

- Все новости

Страстная пятница: история и традиции самого скорбного дня для верующих

В этот день Иисус совершил крестный ход на Голгофу, был распят и умер

06 апреля 2018, 09:05, ИА Амител

»

Фото: www.gospelherald.com

Страстная пятница – самый скорбный день, день траура. Пятница – день воспоминания Спасительных Страстей Господа. В этот день Иисус был предан иудейским властям, совершил крестный ход на Голгофу, был распят и умер. Об истории и традициях праздника читайте в нашей рубрике «Вопрос-ответ».

Что такое Страстная пятница?

Чтобы Иисус Христос воскрес, возвестив победу жизни над смертью, он должен был быть распят. События произошли именно в пятницу. Иисуса пытали, потом судили, потом вели на Голгофу и распяли. После этого тело сняли с креста и погребли в пещере.

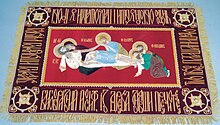

Именно распятие является важным символом Страстной пятницы. Еще один важный символ, которому уделяется внимание во время утренней и вечерней службы, – это плащаница. Длинная ткань, на которой в полный рост изображен Иисус Христос в гробу.

В Великую пятницу священнослужители надевают самое темное облачение и совершают три богослужения. Утром в храмах служат так называемые «Часы», после которых опять читают Евангелие о Страстях Христовых. В середине дня – вечерню с чином выноса плащаницы, а вечером служат утреню Великой субботы с чином погребения плащаницы. Пусть вас не удивляет несоответствие во времени, дело в том, что по церковному календарю сутки начинаются с вечера.

Плащаницу устанавливают на возвышении в центре храма, на нее кладут Евангелие, а перед ней ставят кадильницу с ладаном, постоянно воскуряющую фимиам. Также в память о том, как жены-мироносицы принесли масла для помазания тела Христа, плащаницу умащают благовониями и украшают цветами. Верующие прикладываются к ней, также перед плащаницей положено полагать земные поклоны.

Все богослужения Великой пятницы и Великой субботы начинаются и завершаются не в алтаре, а перед плащаницей. Кроме того, Великая пятница – день строгого поста. Верующие не должны ничего есть до окончания чина выноса плащаницы – до трех часов дня. Затем разрешено вкусить хлеб и выпить воды.

Как проходит богослужение в Страстную пятницу?

В Великую пятницу в Православной Церкви совершают три богослужения. Утром служат Часы, за которыми вновь читают Евангелие о Страстях Христовых, в середине дня совершают вечерню с чином выноса плащаницы, а вечером – утреню Великой субботы (сутки по церковному календарю начинаются с вечера) с чином погребения плащаницы.

Днем на чине выноса плащаницы читается канон «Плач Божией Матери». Вечернее богослужение имеет заупокойный характер. Это погребение Самого Христа. Как на отпевании, все в храме стоят с зажженными свечами. В начале утрени читается семнадцатая кафизма — часть Псалтири, которую обычно читают при отпевании усопших или на панихидах. Затем прочитывают канон Великой субботы. Это тоже плач о погребенном Христе, но в нем все сильнее звучит новая тема – ожидание Воскресения, предчувствие Пасхи. Тихим крестным ходом с плащаницей и со свечами завершается утреня Великой субботы. Когда шествие обходит храм, все поют заупокойное «Святый Боже, Святый Крепкий, Святый Бессмертный, помилуй нас…» Всего несколько часов отделяет этот крестный ход от следующего, совершаемого в воскресную полночь, уже пасхального.

Чем не рекомендуют заниматься в Страстную пятницу?

В Страстную пятницу грехом считается работать в огороде – нельзя втыкать в землю железные предметы: грабли, вилы, лопаты. Урожай может дать хороший только петрушка. Петрушку называют травой предсказателей, и она приносит плодовитость, любовь и страсть.

Если вы изготовите саше с листьями петрушки, то это будет хорошей защитой для вас от физиологического или психологического давления. Также благоприятным этот день считают для прививки деревьев.

А белье, постиранное в Страстную пятницу, чистым не станет, оно может покрыться кровавыми пятнами. В Страстную пятницу не рекомендуется перевозить пчел, иначе погибнут все. Если вы освятите в храме кольца в этот день, то они могут защитить вас от болезней на весь год. Испеченная сдоба в Страстную пятницу, сохраненная в течение всего года, лечит коклюш.

Какие существуют народные приметы в Страстную пятницу?

В дни Пасхи не берут соль, чтобы руки не потели, девушки становятся на топор, чтобы стать крепкими. Все любовные приметы на Пасху сбываются особенно верно. Если девушка ушибет локоть, то ее вспоминает милый. Если в супе попадется муха или таракан — жди свидания. Губа зачешется — не миновать поцелуев, если бровь — кланяться девушке с милым.

Если на Страстную пятницу пасмурно, то хлеб будет с бурьяном. Если солнечно — пшеница будет зернистой.

Простой способ определения «наговоренных» вещей в квартире. Так, в Страстную пятницу идете в церковь и берете недогоревшую свечку, которая была у вас в руках во время службы. В квартире ее зажигаете и идете по комнатам. Там, где она затрещит, находится порченая вещь.

Если подстригать ногти в Страстную пятницу, это помогает от зубной боли. Во сне в этот день девушке явится будущий жених.

Материал впервые был опубликован 29 апреля 2016 года

Великая Пятница – что означает этот день для христиан? Какие молитвы совершаются в Великую Пятницу? Как провести этот день?

Содержание статьи

- Великая Пятница

- Великая Пятница. Предательство Иуды

- Великая Пятница. Путь на Голгофу

- Великая Пятница. Распятие

- Покаяние благоразумного разбойника

- Смерть Христова

- Великая Пятница. Погребение Господа Иисуса Христа

- Читать также о Великой Пятнице:

- Великая Пятница. Видео по теме:

Великая Пятница

Великая Пятница – самый скорбный день в году.

Днесь висит на древе, Иже на водах землю повесивый: венцем от терния облагается, Иже Ангелов Царь: в ложную багряницу облачается, одеваяй небо облаки: заушение прият, Иже во Иордане свободивый Адама: гвоздьми пригвоздися Жених Церковный: копием прободеся Сын Девы. Покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе: покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе: покланяемся Страстем Твоим, Христе, покажи нам и славное Твое Воскресение. «Ныне висит на древе Тот, Кто повесил (утвердил) землю на водах; терновым венцом покрывается Ангелов Царь; в порфиру шутовскую одевается Одевающий небо облаками; заушения (пощечины) принимает Освободивший (от греха) Адама в Иордане; гвоздями прибивается Жених Церкви; копьем пронзается Сын Девы. Поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, поклоняемся страданиям Твоим, Христе, покажи нам и всеславное Твое Воскресение».

В Великую Пятницу воспоминаются Крестные страдания и смерть Господа Иисуса Христа.

Утреня Великой Пятницы служится в четверг вечером – читаются Двенадцать Евангелий, повествующих о страданиях Христовых.

Великая Пятница, когда умер на кресте Спаситель, – это тот день в году, когда не служится Божественная Литургия: она считается совершенной Христом на Кресте. Вместо Литургии совершаются Царские Часы – чтение в храме перед Крестом псалмов и Евангелия о страстях Господних.

Пятница – день крестной смерти Христа – постный в течение всего года, в саму же Великую Пятницу соблюдается строгий пост: по уставу в этот день вкушать пищу могут только больные и дети и только после захода солнца. Однако в связи с тем, что служба вечерни совершается днем в пятницу, во многих храмах дозволяется вкушать пищу после службы выноса Плащаницы.

Вынос Плащаницы в Великую Пятницу – иконы Христа, лежащего во гробе – совершается, как правило, днем. Примерно в два или три часа дня Плащаницу выносят из алтаря и устанавливают в центре храма – во «гробе» – возвышении, украшенном цветами.

«Перед нами гроб Господень. В этом гробе человеческой плотью предлежит нам многострадальный, истерзанный, измученный Сын Девы. Он умер; умер не только потому, что когда-то какие-то люди, исполненные злобы, Его погубили. Он умер из-за каждого из нас, ради каждого из нас. Скажете: как мы за это ответственны – мы же тогда не жили?! Да, не жили! А если бы теперь на нашей земле явился Господь – неужели кто-нибудь из нас может подумать, что он оказался бы лучше тех, которые тогда Его не узнали, Его не полюбили, Его отвергли.

Те люди, которые тогда это совершили, были действительно страшны, но нашей же посредственностью, нашим измельчанием. Они такие же, как мы; их жизнь слишком узкая для того, чтобы в нее вселился Бог; жизнь их слишком мала и ничтожна для того, чтобы та любовь, о которой говорит Господь, могла найти в ней простор и творческую силу. И эти люди, подобно нам, это сделали. «Подобно нам», потому что сколько раз в течение нашей жизни мы поступаем как тот или другой из тех, которые участвовали в распятии Христа. Посмотрите на Пилата: он старался сохранить свое место, он старался не подпасть под осуждение своих начальников, старался не быть ненавидимым своими подчиненными, избежать мятежа. И хотя и признал, что Иисус ни в чем не повинен, а отдал Его на погибель» – проповедует митрополит Антоний Сурожский.

Песнопения Вечерни Великой Пятницы посвящены страданиям и смерти Христовым. После малого повечерия с чтением канона о распятии Господнем и на плач Пресвятой Богородицы – во время службы утрени Великой Субботы совершается Крестный ход с пением погребального «Святый Боже…»: Святая Плащаница обносится вокруг храма. По окончании чина погребения Плащаница полагается на середину храма для поклонения священнослужителей и богомольцев.

Читать также — Великая Пятница. Исповедь Бога

Великая Пятница. Предательство Иуды

Архиеп. Аверкий (Таушев): Евангелист Матфей рассказывает нам о дальнейшей участи Иуды предателя. «Видев Иуда, предавая Его, яко осудишь Его, раскаялся возврати тридесять сребреники архиереем и старцем» – возможно, конечно, что Иуда не ожидал смертного приговора для Иисуса или вообще, ослепленный сребролюбием, не думал о последствиях, к которым приведет его предательство.

Когда же его Учитель был осужден, в нем, уже насытившемся обладанием сребрениками, вдруг проснулась совесть: пред ней предстал весь ужас его безумного поступка. Он раскаялся, но, к несчастью для него, это раскаяние было соединено в нем с отчаянием, а не с надеждой на всепрощающее милосердие Божие. Это раскаяние есть только невыносимое мучение совести, без всякой надежды на исправление, почему оно бесплодно, бесполезно, почему и довело Иуду до самоубийства. «Возвратил тридцать сребреников» – то, что еще недавно казалось для него таким заманчивым, теперь, когда совесть заговорила, показалось для него отвратительным. Таков и всякий грех вообще. Ему надо было бы не сребреники повергать перед первосвященниками, а самому повергнуться перед Господом Иисусом Христом, умоляя Его о прощении своего греха, и тогда он, конечно, был бы прощен.

Но он думает без помощи свыше, одними своими силами как-то поправить сделанное: возвращает сребреники, свидетельствуя при этом: «Согрешил, предав кровь неповинную». Это свидетельство, по словам св. Златоуста, умножает вину и его и их, первосвященников: «Его – потому, что он не раскаялся, или раскаялся, но уже поздно, и сам произнес осуждение для себя, ибо сам исповедал, что предал Господа напрасно; их вину умножает потому, что они, тогда как могли раскаяться и переменить свои мысли, не раскаялись». Бессердечно, холодно и насмешливо отнеслись они к Иуде: «Что нам до того? Смотри сам». Это указывает на их крайнее нравственное огрубение. «И бросив сребреники в храме, он вышел: пошел и удавился». Не взятые ими из его рук деньги он бросил в храме, думая, может быть, этим успокоить мучения совести, но напрасно: мучения эти довели его до такого отчаяния, что он пошел и повесился, после чего, вероятно, упал с той высоты, на которой висел, так как ап. Петр в кн. Деяний (1:18) свидетельствует, что «когда низринулся, расселось чрево его, и выпали все внутренности его».

При всей своей развращенности, первосвященники признали все-таки невозможным употребить эти деньги в пользу храма – «вложить их в корвану», то есть в сокровищницу церковную, так как это была «цена крови». Впрочем, вероятно, они основывались на Втор. 23:18, и в этом случае обнаружилось их крайне злое чувство в отношении к Господу Иисусу Христу, как обнаружилось оно и в том, что они оценили предательство Его 30 сребрениками. Поразительно ярко характеризует фарисеев это стремление исполнить менее важный закон, нарушив более важный – не осуждать невинных. «Купила на них село скудельниче» – поле известного горшечника, ни на что негодное, так как там копалась глина и обжигались горшки, «в погребение странников» – иудеев и прозелитов, в огромном количестве собиравшихся в Иерусалиме на праздник Пасхи и другие большие праздники. Тогда сбылось сказанное Иеремиею пророком: и прияв тридесять сребреник, цену Цененного, его же оценили сыны Израилевы: «И дали за землю горшечника». Ничего похожего на эти слова у пророка Иеремии мы не находим: единственное место в 32:7 говорит вообще о факте покупки поля. Возможно, что это вставка позднейшего переписчика.

Великая Пятница. Путь на Голгофу

О крестном пути Господа повествуют все четыре Евангелиста. Первые два – св. Матфей и св. Марк – говорят о нем совершенно одинаково. «И когда насмеялись над Ним, сняли с Него багряницу и одели Его в одежды Его, и повели Его на распятие. Выходя, они встретили одного Киринеянина, по имени Симона; сего заставили нести крест Его». Св. Иоанн говорит совсем коротко, ничего не упоминая о Симоне Киринейском. Подробнее всех говорит св. Лука. Как сообщает об этом св. Иоанн и как это вообще было принято с осужденными на смерть через распятие, Господь Сам нес Свой крест на место казни. Но Он был так истомлен и Гефсиманским внутренним борением, и без сна проведенной ночью, и страшными истязаниями, что оказался не в силах донести крест до места назначения. Не из сострадания, конечно, но из желания скорее дойти, чтобы завершить свое злое дело, враги Господа захватили по пути некоего Симона, переселенца из Киринеи, города в Ливии на северном берегу Африки к западу от Египта (где жило много евреев, издавна туда переселившихся), и заставили его понести крест Господа, когда он возвращался с поля в город. Св. Марк добавляет, что Симон был отцом Александра и Руфа, известных потом в первенствующей христианской церкви, о которых упоминает в посл. к Римл. 16:13 св. ап. Павел.

Св. Лука добавляет, что «шло за Ним великое множество народа и женщин, которые плакали и рыдали о Нем». Не только враги, но и почитатели Господа, сострадавшие Ему, шли за Ним. Несмотря на обычай, согласно которому запрещалось преступнику, ведомому на казнь, выражать сочувствие, бывшие в этой толпе народа женщины громко, рыданиями изъявляли свое сострадание Господу. Выраженное ими сострадание было столь глубоко и искренно, что Господь счел нужным отозваться и обратился к ним с целою речью, надо полагать, в то время, когда произошла остановка в шествии при возложении креста Христова на Симона Киринеянина. «Дочери Иерусалимские! Не плачьте обо Мне, но плачьте о себе и о детях ваших»… «Дочери Иерусалимские» – ласковое обращение, указывающее на благорасположение Господа к этим женщинам, выражавшим Ему такое трогательное сочувствие. Господь как бы забывает о предстоящих Ему страданиях, и духовный взор Его обращается к будущему избранного народа, к тому страшному наказанию, которое постигнет его за отвержение Мессии. «Плачьте о себе и о детях ваших» – в этих словах Господь предупреждает их о бедствиях, имеющих постигнуть их и детей их.

Тут Он как будто имеет в виду ту страшную клятву, которую так легкомысленно навлекли на себя иудеи, кричавшие: «Кровь Его на нас и на детях наших» (Матф. 27:25). «Се, дни грядут»… – приходят, приближаются дни страшных бедствий, когда высшее благословение чадородия превратится в проклятие, и будут считаться блаженными те, которые считались ранее находящимися под гневом Божьим, как неплодные, не рождающие. «Тогда начнут говорить горам: падите на нас!» – столь велики будут бедствия. Речь здесь идет, несомненно, о разрушении Иерусалима Титом в 70-м году по Р. Х.

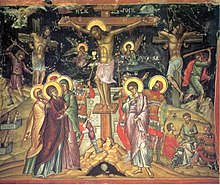

Великая Пятница. Распятие

Согласно повествованию всех четырех Евангелистов, Господа привели на место, называемое Голгофа, что значит «лобное место», и там распяли Его в Великую Пятницу посреди двух разбойников, о которых св. Лука сообщает, что их тоже вели на смерть вместе с Ним. Голгофа, или «лобное место», – это был небольшой холм, находившийся в то время вне городских стен Иерусалима к северо-западу. Неизвестно точно, почему этот холм носил такое название. Думают, что или потому, что он имел вид черепа, или потому, что на нем находилось много черепов казненных там людей. По древнему преданию, на этом же самом месте был погребен прародитель Адам.

Св. ап. Павел в послании к Евреям 13:11-12 указывает на особое значение того, что «Иисус пострадал вне врат». Когда Иисуса привели на Голгофу, то давали Ему пить, по св. Марку 15:23, вино со смирною, а по святому Матфею 27:34, уксус, смешанный с желчью. Это – напиток, одуряющий и притупляющий чувство, который давали осужденным на казнь через распятие, чтобы несколько уменьшить мучительность страданий. Римляне называли его «усыпительным». По свидетельству еврейских раввинов, это было вино, в которое подбавлялась смола, благодаря чему вино помрачало сознание осужденного и тем облегчало для него муки. Смирна – один из видов смолы, почему ее и указывает св. Марк. Приправа вина смолой давала крайне едкий и горький вкус, почему св. Матфей называет ее «желчью», а вино, как очевидно уже скисшее, называет «уксусом». «И, отведав, не хотел пить» – желая претерпеть всю чашу страданий до конца, в полном сознании, Господь не стал пить этого напитка.

«Был час третий, и распяли Его» – так говорит св. Марк о событиях Великой Пятницы (15:25). Это как будто противоречит свидетельству св. Иоанна о том, что еще в шестом часу Господь был на суде у Пилата (Иоан. 19:14). Но надо знать, что по примеру ночи, делившейся на четыре стражи, по три часа в каждой, и день делился на четыре части, называвшиеся по последнему часу каждой части: час третий, час шестой и час девятый. Если предположить, что окончательный приговор был произнесен Пилатом с лифостротона по истечении третьего часа по иудейскому счету, то есть по теперешнему времени – в 9 с небольшим часов утра, то св. Иоанн вполне мог сказать, что это был час шестой, ибо начиналась вторая четверть дня, состоявшая из 4-го, 5-го и 6-го часов, которая у евреев называлась по своему последнему часу шестым часом. С другой стороны, св. Марк мог сказать, что это был час третий, потому что шестой час, в смысле второй четверти дня, еще только начинался, а истек лишь третий час, в смысле первой четверти дня Великой Пятницы.

«И распяли Его» – кресты бывали различной формы, и распинали по-разному, иногда пригвождая ко кресту, лежащему на земле, после чего крест поднимали и водружали в земле вертикально; иногда же сперва водружали крест, а потом поднимали осужденного и пригвождали его. Иногда распинали вниз головой (так распят был, по собственному желанию, св. ап. Петр). Руки и ноги иногда пригвождались гвоздями, иногда только привязывались. Тело распятого беспомощно свешивалось в ужасных конвульсиях, все мускулы сводила мучительная судорога, язвы от гвоздей, под тяжестью тела, раздирались, казненного томила невыносимая жажда, вследствие жара от гвоздичных язв и потери крови.

Страдания распятого были столь велики и невероятно мучительны, а к тому же и длительны (иногда распятые висели на крестах, не умирая, по трое суток и даже более), что казнь применялась лишь к самым большим преступникам и считалась самой ужасной и позорной из всех видов казни. Дабы руки не разорвались преждевременно от ран, под ноги иногда прибивали подставку-перекладину, на которую распинаемый мог встать. На верхнем, оставшемся свободном конце креста, прибивалась поперечная дощечка с написанием вины распятого.

Среди неописуемых страданий Господь не оставался совершенно безмолвным: Он семь раз говорил с креста в Великую Пятницу. Первыми Его словами была молитва за распинателей, вторыми словами Своими Он удостоил благоразумного разбойника райского блаженства, третьими словами — поручил Свою Пречистую Матерь св. ап. Иоанну, четвертые слова Его – возглашение: «Боже Мой, Боже Мой! Для чего Ты Меня оставил?», пятое слово – «Жажду», шестое – «совершилось», седьмое – «Отче, в руки Твои предаю дух Мой».

Первыми словами Господа в Великую Пятницу была молитва за распинателей, которую приводит св. Лука (23:34): «Отче! Прости им, ибо не ведают, что творят». Никто из распинавших Христа не знал, что Он – Сын Божий. «Ибо, если бы познали, то не распяли бы Господа славы» (1 Кор. 2:8), говорит св. ап. Павел. Даже и иудеям св. ап. Павел говорил в своей второй проповеди при исцелении хромого: «Вы, как и начальники ваши, сделали это по неведению» (Деян. 3:17). Римские воины, конечно, не знали, что они распинают Сына Божия; осудившие на смерть Господа иудеи до такой степени были ослеплены в своей злобе, что действительно не думали, что они распинают своего Мессию. Однако такое неведение не оправдывает их преступления, ибо они имели возможность и средства знать. Молитва Господа свидетельствует о величии Его духа и служит нам примером, чтобы и мы не мстили своим врагам, но молились за них Богу.

«Пилат же написал надпись»... Св. Иоанн свидетельствует о том, что по приказу Пилата написана была дощечка с указанием вины Господа, как это было обыкновенно принято (Иоан. 19:19-22). Желая еще раз уязвить членов синедриона, Пилат приказал написать: «Иисус Назарянин Царь Иудейский». Так как члены синедриона обвиняли Господа в том, что Он присвоил Себе царское достоинство, то Пилат и приказал написать эту Его вину, в посрамление синедриону; царь иудейский распят по требованию представителей народа иудейского. Вопреки обычаю, надпись была сделана на трех языках: еврейском местном, национальном, греческом – тогда общераспространенном и римском – языке победителей. Цель этого была та, чтобы каждый мог прочесть эту надпись. Не думая о том, Пилат исполнил этим высшую промыслительную цель: в минуты самого крайнего Своего унижения Господь Иисус Христос на весь мир был объявлен Царем. Обвинители Господа восприняли это как злую насмешку и требовали, чтобы Пилат изменил надпись, но гордый римлянин резко отказал им в этом, дав почувствовать им свою власть.

«Распявшие Его делили одежды Его, бросая жребий»... Римский закон отдавал в собственность воинов, совершавших казнь, одежды распинаемых. Совершавших распятие, по свидетельству Филона, бывало четверо. Св. Иоанн, подробнее других рассказывающий о разделении одежды Господа, так и говорит, что верхнюю одежду воины разорвали на четыре части, «каждому воину по части», а нижняя одежда – хитон – была не шитая, а тканная, или вязанная сверху, то есть начиная с отверстия для головы вниз. Если разорвать такой хитон, то части его не будут иметь никакой ценности. Поэтому о нем был брошен воинами жребий, для того, чтобы он достался одному в целом виде. По преданию, этот хитон был выткан Пречистою Матерью Божьею. Делая это, воины бессознательно, конечно, исполнили древнее пророчество о Мессии из Псалма 21:19, которое и приводит св. Иоанн, повествуя об этом: «Разделили ризы Мои между собою, и об одежде Моей бросали жребий».

Далее первые три Евангелиста повествуют о насмешках и хулениях, которым подвергали Господа в Великую Пятницу как воины, так и проходящие враги Его из народа, а особенно, конечно, первосвященники с книжниками, старейшинами и фарисеями. Хуления эти имели одну общую основу в сопоставлении прошедшего с настоящим. Вспоминая все то, что в прошлом говорил Господь и делал, они указывали на теперешнюю Его беспомощность и насмешливо предлагали Ему совершить явное для всех и очевидное чудо – сойти с креста, обещая, лицемерно, конечно, в таком случае уверовать в Него. В этих хулениях, по словам св. Матфея, принимали участие и разбойники, распятые по правую и по левую сторону от Господа.

Читать также — Великая Пятница — толкования, проповеди, песнопения (+аудио)

Покаяние благоразумного разбойника

(Луки 23:39-43)

Дополняя повествование первых двух Евангелистов о событиях Великой Пятницы, св. Лука передает о покаянии и обращении к Господу одного из двух разбойников. В то время как один из них, видимо, еще более озлобившись от мучений и ища предмет, на который можно было бы обратить свое озлобление, стал, по примеру врагов Господа, хулить Его, подражая им, другой разбойник, очевидно не в такой степени испорченный, сохранивший чувство религиозности, стал усовещивать своего товарища. «Или ты не боишься Бога, когда и сам осужден на то же? И мы осуждены справедливо, потому что достойное по делам нашим приняли; а Он ничего худого не сделал». Очевидно, он слышал плач и терзания иерусалимских женщин, сопровождающих Господа на Голгофу; произвела, быть может, на него впечатление надпись, сделанная на кресте Господа, задумался он над словами врагов Господа: «иных спасал», но, может быть, важнейшей проповедью о Христе была для него молитва Христова о Его врагах-распинателях.

Так или иначе, но совесть в нем сильно заговорила, и он не побоялся среди хулений и насмешек открыто выступить в защиту Господа в Великую Пятницу. Мало того, в его душе произошел такой решительный перелом, что он, ярко выражая свою веру в распятого Господа как в Мессию, обратился к Нему с покаянными словами: «Помяни меня, Господи, когда приидешь во Царствие Твое!» Иначе сказать: «Вспомяни обо мне, Господи, когда будешь царствовать». Он не просит славы и блаженства, но молит о самом меньшем, как хананеянка, желавшая получить хотя бы крупицу от трапезы Господней. Слова благоразумного разбойника стали с той поры для нас примером истинного глубокого покаяния и даже вошли у нас в богослужебное употребление. Это удивительное исповедание ярко свидетельствовало о силе веры покаявшегося разбойника. Страждущего, измученного, умирающего он признает Царем, который придет в Царствие Свое, Господом, Который оснует это Царство. Это такое исповедание, которое не под силу было даже ближайшим ученикам Господа, не вмещавшим мысли о страждущем Мессии. Несомненно тут и особое действие благодати Божьей, озарившей разбойника, дабы он был примером и поучением всем родам и народам. Это его исповедание заслужило высочайшую награду, какую только можно себе представить. «Ныне же будешь со Мною в раю» – сказал ему Господь, то есть сегодня же он войдет в рай, который вновь откроется для людей через искупительную смерть Христову в Великую Пятницу.

Смерть Христова

(Матф. 27:45-56; Марк. 15:33-41; Лук. 23:44-49; Иоан. 19:28-37)

По свидетельству первых трех Евангелистов, смерти Господа на кресте в Великую Пятницу предшествовала тьма, покрывшая землю: «В шестом же часу настала тьма по всей земле, и продолжалась до часа девятого», то есть по нашему времени – от полудня до трех часов дня. Лука добавляет к этому, что «померкло солнце». Это не могло быть обыкновенное солнечное затмение, так как на еврейскую Пасху 14 Нисана всегда бывает полнолуние, а солнечное затмение случается только при новолунии, но не при полнолунии. Это было чудесное знамение, которое свидетельствовало о поразительном и необычайном событии – смерти возлюбленного Сына Божия. Об этом необыкновенном затмении солнца, в продолжении которого даже видны были звезды, свидетельствует римский астроном Флегонт. Об этом же необыкновенном солнечном затмении свидетельствует и греческий историк Фалос. Вспоминает о нем в своих письмах к Аполлофану св. Дионисий Ареопагит, тогда еще бывший язычником. Но замечательно, как подчеркивает св. Златоуст и блаж. Феофилакт, что эта тьма «была по всей земле», а не в какой-либо части только, как это бывает при обычном затмении солнца. Видимо, эта тьма последовала вслед за глумлениями и насмешками над распятым Господом; она же и прекратила эти глумления, вызвав то настроение в народе, о котором повествует св. Лука: «И весь народ, сошедший на сие зрелище, видя происходившее, возвращался, бия себя в грудь» (Лук. 23:48).

«В девятом часу возопил Иисус громким голосом: «Или, Или! Ламма савахфани?» Эти слова св. Марк передает как «Элои», вместо «Или». Этот вопль, конечно, не был воплем отчаяния, но только выражением глубочайшей скорби души Богочеловека. Для того, чтобы искупительная жертва совершилась, необходимо было, чтобы Богочеловек испил до самого дна всю чашу человеческих страданий. Для этого потребовалось, чтобы распятый Иисус не чувствовал радости Своего единения с Богом Отцом. Весь гнев Божий, который, в силу Божественной правды, должен был излиться на грешное человечество, теперь как бы сосредоточился на одном Христе, и Бог как бы оставил Его в Великую Пятницу. Среди самых тяжких, какие только можно представить, мучений телесных и душевных, это оставление было наиболее мучительным, почему и исторгло из уст Иисуса это болезненное восклицание.

По-еврейски «Илия» произносилось «Елиагу». Поэтому вопль Господа в Великую Пятницу послужил новым поводом к насмешкам над Ним: «Вот, Илию зовет». Язвительность насмешки этой состояла в том, что перед пришествием Мессии иудеи ожидали прихода Илии. Насмехаясь над Господом, они как бы хотели сказать: вот Он и теперь еще, распятый и поруганный, всё еще мечтает, что Он – Мессия, и зовет Илию Себе на помощь. Первые два Евангелиста говорят, что тотчас же один из воинов побежал, взял губку, наполнил уксусом и, наложив на трость, давал ему пить. Очевидно, это было кислое вино, которое было обыкновенным питанием римских воинов, особенно в жаркую погоду. Губку, впитывавшую в себя жидкость, воин наложил на трость, по св. Иоанну, «иссоп», то есть ствол растения, носящего это имя, так как висевшие на кресте находились довольно высоко от земли, и им нельзя было просто поднести пития. Распятие производило невероятно сильную, мучительную жажду в страдальцах, и св. Иоанн сообщает, что Господь произнес, очевидно перед этим: «Жажду» (19:28-30), добавляя при этом: «Да сбудется Писание». Псалмопевец в 68 Пс. 22 ст., изображая страдания Мессии, действительно предрек это: «И в жажде моей напоили меня уксусом». Вкусив уксус, по свидетельству св. Иоанна, Господь возгласил: «Совершилось!» то есть: совершилось дело, предопределенное в Совете Божием, – совершилось искупление человеческого рода и примирение его с Богом через смерть Мессии (Иоан. 19:30)

По словам св. Луки, вслед за тем Господь воскликнул: «Отче! В руки Твои предаю дух Мой» (Лук. 23:46) «и, преклонив главу, предал дух» (Иоан. 19:30). Все три первых Евангелиста свидетельствуют, что в этот момент смерти Иисуса «завеса в храме разорвалась надвое, сверху до низу», то есть сама собой разодралась на две части та завеса, которая отделяла Святилище в храме от Святого Святых. Так как это было время принесения вечерней жертвы – около 3 часов пополудни по нашему времени, – то, очевидно, очередной священник был свидетелем этого чудесного саморазрывания завесы.

Это символизировало собой прекращение Ветхого Завета в Великую Пятницу и открытие Нового Завета, который отверзал людям вход в закрытое дотоле Царство Небесное. «Земля потряслась» – произошло сильное землетрясение, как знак гнева Божья на тех, кто предал смерти Сына Его Возлюбленного. От этого землетрясения «камни распались», то есть скалы расселись, и открылись делавшиеся в них погребальные пещеры. В знамение победы Господа над смертью – «многие тела усопших святых воскресли» – воскресли погребенные в этих пещерах тела умерших, которые на третий день, по воскресении Господа, явились в Иерусалиме знавшим их людям.

Все три Евангелиста свидетельствуют, что эти чудесные знамения, сопровождавшие смерть Господа, произвели столь сильное, потрясающее действие на римского сотника, что он произнес, по первым двум Евангелистам: «Воистину Он был Сын Божий!», а по св. Луке: «Истинно Человек Этот был праведник!» Предание говорит, что этот сотник, по имени Лонгин, стал христианином и позже мучеником за Христа (память его 16 окт.).

По свидетельству св. Луки, потрясен был и весь народ, собравшийся у Голгофы: «Возвращался, бия себя в грудь» – такие резкие переходы от одного настроения к другому естественны в возбужденной толпе. Все три Евангелиста указывают, что свидетелями смерти Господа и происшедших при этом событий были «все знавшие Его, и женщины, следовавшие за Ним из Галилеи, которые стояли вдали и смотрели на это», и среди них, как перечисляют св. Матфей и Марк поименно, находились: Мария Магдалина, Мария – мать Иакова и Иосии и мать сынов Зеведеевых, Саломия.

О дальнейшем, что произошло по смерти Иисуса в Великую Пятницу и до Его погребения, повествует, дополняя, как и всегда, первых трех Евангелистов, только св. Иоанн, бывший, как он тут же утверждает, сам свидетелем всего этого. Так как была пятница – по-гречески «параскеви», что значит «приготовление», то есть «день перед субботой», а суббота та была «великим днем», так как совпадала с первым днем Пасхи, то, дабы не оставлять на крестах тела распятых в этот «великий день», иудеи, то есть враги Господа, или члены синедриона, просили Пилата «перебить у них голени» и, умертвив их таким образом, «возьмут», то есть снимут и похоронят еще до наступления вечера, когда надо было уже вкушать Пасху. По жестокому римскому обычаю, распятым, для ускорения их смерти, перебивали голени, то есть раздробляли ноги. Получив это разрешение Пилата, воины перебили голени у разбойников, распятых со Иисусом, которые были еще живы. «Но, пришедши к Иисусу, как увидели Его уже умершим, не перебили у Него голеней; но один из воинов копьем пронзил Ему ребра, и тотчас истекла кровь и вода» (Ин. 19:33-34; 1 Ин. 5:8).

Отрицательная критика очень много занималась вопросом, могла ли из мертвого тела Иисуса истечь кровь и вода, и доказывала, что это невозможно, так как из мертвого застывшего тела не может истекать кровь, ибо она находится в жидком состоянии в мертвом теле весьма недолго, не более часа, а что отделение водянистой жидкости начинается лишь с наступлением разложения, да еще при некоторых болезнях, как напр., при тифозной горячке, лихорадке и т.п. Все эти рассуждения неосновательны. Ведь мы не знаем всех подробностей распятия и смерти Господа, а потому и не можем судить об этих деталях. Но общеизвестен факт, что у распятых наступает именно лихорадочное состояние. Да и само прободение ребра произошло, несомненно, очень скоро после смерти и уж во всяком случае не более, чем через час, ибо наступал вечер, и иудеи спешили окончить свое злое дело.

Кроме того, нет при этом надобности рассматривать это истечение крови и воды как явление естественное. Сам св. Иоанн, подчеркивающий его в своем Евангелии, видимо отмечает его как явление чудесное («И видевший засвидетельствовал, и истинно свидетельство его» – 19:35). Чистейшее Тело Богочеловека и не могло подвергнуться обыкновенному закону разложения человеческого тела, а, вероятно, с самой минуты смерти начало входить в то состояние, которое окончилось воскресением Его в новом, прославленном, одухотворенном виде. Символически это истечение крови и воды свв. Отцы объясняют как знамение таинственного способа единения верующих со Христом в таинствах Крещения и Евхаристии: «Водою мы рождаемся, а кровью и телом питаемся» (бл. Феофилакт и св. Златоуст). Св. Иоанн, стоявший при кресте и видевший все это, свидетельствует и то, что он говорит истину, и то, что и сам он не обманывается, утверждая это – «И истинно свидетельство его» (Иоан. 19:35).

Излияние воды и крови из прободенного ребра Христова в Великую Пятницу есть знамение того, что Христос сделался нашим Искупителем, очистив нас водою в таинстве Крещения и Своею Кровью, которой напояет нас в таинстве Причащения. Вот почему тот же ап. Иоанн в своем 1-м соборном послании говорит: «Сей есть Иисус Христос, пришедший водою и кровью и Духом, не водою только, но водою и кровью; и Дух свидетельствует о Нем, потому что Дух есть истина. Ибо три свидетельствуют на небе: Отец, Слово и Святой Дух; и Сии три суть едино. И три свидетельствуют на земле: Дух, вода и кровь; и сии три об одном» (1 Иоан. 5:6-8).

«Ибо сие произошло», то есть не только прободение ребра, но и то, что у Господа не были перебиты голени, «да сбудется Писание: кость Его да не сокрушится». Это было предсказано в кн. Исход 12:46: Пасхальный агнец, преобразовавший Господа Иисуса Христа, должен был быть вкушаем без сокрушения костей, а всё оставшееся должно было быть предано огню. «Также и в другом месте Писание предсказывает: Воззрят на Того, Которого пронзили» – это заимствовано из кн. пр. Захарии 12:10. В этом месте Иегова в лице Мессии представляется как пронзенный народом своим, и этот самый народ, при взгляде на пронзенного, представляется приносящим пред Ним покаяние с плачем и рыданием. Эти слова постепенно исполнялись на иудеях, коими Господь был предан смерти, и будут исполняться до кончины мира, перед которой произойдет всеобщее обращение иудеев ко Христу, как предрекает это св. ап. Павел в послании к Римлянам 11:25-26.

Великая Пятница. Днесь висит на Древе (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы»)

Великая Пятница. Не рыдай Мене, Мати (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы»)

Разбойника Благоразумнаго (Женский хор. Диск «Время поста и молитвы»)

Великая Пятница. Погребение Господа Иисуса Христа

(Мф. 27:57-66; Марк. 15:42-47; Лук. 23:50-56; Иоан. 19:38-42)

О погребении Господа повествуют совершенно согласно все четыре Евангелиста, причем каждый сообщает свои подробности. Погребение состоялось при наступлении вечера, но суббота еще не наступила, хотя и приближалась, то есть, надо полагать, это было за час или за два до захода солнца, с которого уже начиналась суббота. Это ясно указывают все четыре Евангелиста: Матф. 27:57, Марк. 15:42, Лук. 23:54 и Иоан. 19:42, а особенно подчеркивают св. Марк и Лука.

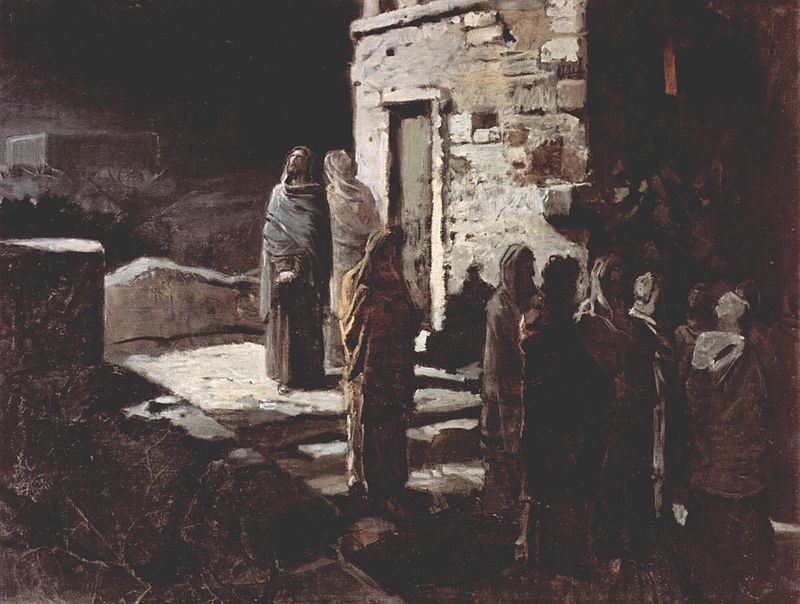

Пришел Иосиф из Аримафеи, иудейского города вблизи Иерусалима, член синедриона, как свидетельствует св. Марк, человек благочестивый, потаенный ученик Христов, по свидетельству св. Иоанна, который не участвовал в осуждении Господа (Лук. 23:51). Пришедши к Пилату, он испросил у него тело Иисуса для погребения. По обычаю римлян, тела распятых оставались на крестах и делались добычей птиц, но можно было, испросив разрешения начальства, предавать их погребению. Пилат выразил удивление тому, что Иисус уже умер, так как распятые висели иногда по несколько дней, но, проверив через сотника, который удостоверил ему смерть Иисуса, повелел выдать тело Иосифу. По повествованию св. Иоанна, пришел и Никодим, приходивший прежде ко Иисусу ночью (см. Иоан. 3 гл.), который принес состав из смирны и алое около 100 фунтов.

Иосиф купил плащаницу – длинное и ценное полотно. Они сняли Тело, умастили его, по обычаю, благовониями, обвили плащаницей и положили в новой погребальной пещере в саду Иосифа, находившемся неподалеку от Голгофы. Так как солнце уже склонялось к западу, все делалось хотя и старательно, но очень поспешно. Привалив камень к дверям гроба, они удалились. За всем этим наблюдали женщины, стоявшие прежде на Голгофе.

Св. Златоуст, а за ним и бл. Феофилакт, считают, что упоминаемая Евангелистами «Мария, Иакова и Иосии мать» есть Пресвятая Богородица, «поскольку Иаков и Иосия были дети Иосифа от первой его жены. А так как Богородица называлась женой Иосифа, то по праву называлась и матерью, то есть мачехою детей его». Однако другие того мнения, что это была Мария, жена Клеопы, двоюродная сестра Богоматери.

Все они сидели против входа в пещеру, как свидетельствует о том св. Матфей (27:61), а затем, по свидетельству св. Луки, возвратившись, приготовили благовония и масти, чтобы по окончании дня субботнего покоя прийти и помазать Тело Господа, по иудейскому обычаю (Лук. 23:56). По сказанию св. Марка, эти женщины, именуемые «мироносицами», купили ароматы не в самый день погребения Господа, а по прошествии субботы, то есть в субботу вечером. Тут нельзя видеть противоречия. В пятницу вечером оставалось, очевидно, очень мало времени до захода солнца. Отчасти, что успели, они приготовили еще в пятницу, а чего не успели, закончили в субботу вечером.

Евангелист Матфей сообщает еще об одном важном обстоятельстве, происшедшем на другой день после погребения – «На другой день, который следует за пятницею», то есть в субботу, первосвященники и фарисеи собрались к Пилату, не думая даже о нарушении субботнего покоя, и попросили его дать распоряжение об охране гроба до третьего дня. Просьбу свою они мотивировали заявлением: «Мы вспомнили, что обманщик тот, еще будучи в живых, сказал: «после трех дней воскресну»; итак прикажи охранять гроб до третьего дня, чтоб ученики Его, пришедши ночью, не украли Его и не сказали народу: «Воскрес из мертвых»; и будет последний обман хуже первого». «Первым обманом» они называют здесь то, что Господь Иисус Христос учил о Себе как о Сыне Божьем, Мессии, а «последним обманом» – проповедь о Нем как о восставшем из гроба Победителе ада и смерти. Этой проповеди они боялись больше, и в этом они правы были, что показала и вся дальнейшая история распространения христианства.

На эту просьбу Пилат ответил им сухо: «Имеете стражу; пойдите, охраняйте, как знаете». В распоряжении членов синедриона находилась на время праздников стража из римских воинов, которой они пользовались для охранения порядка и спокойствия, ввиду громадного стечения народа из всех стран в Иерусалим. Пилат предлагает им, использовав эту стражу, сделать все так, как они сами хотят, дабы потом они никого не могли винить ни в чем. «Они пошли и поставили у гроба стражу, и приложили к камню печать» – то есть, вернее, камень, которым он был закрыт, шнуром и печатью, в присутствии стражи, которая потом осталась при гробе, чтобы его охранять.

Таким образом, злейшие враги Господа, сами того не подозревая, подготовили неоспоримые доказательства Его славного воскресения из мертвых.

«К этим святым воспоминаниям искупительной жертвы Господа и Спасителя нашего готовила нас Святая Церковь в течение всего Великого поста, – напоминал в одной из своих проповедей Патриарх Алексий II, – но человечество продолжает грешить. И если мы не каемся в своих грехах, если не стараемся построить жизнь по Христовым заповедям, то тем самым сораспинаем нашего Спасителя и Искупителя Господа Иисуса Христа. Разве мы с терпением несем свой жизненный крест? Но ведь каждому крест дается по его силам, не бывает креста выше сил человеческих.

Вспомним, не унываем ли мы, обращаемся ли с горячей молитвой ко Господу, начинаем и заканчиваем ли ею день свой? Испрашиваем ли мы благословения Божия на каждое дело, к которому приступаем? А ведь молитва имеет огромную силу, она помогает нам нести наш жизненный крест и подает нам терпение, помогает не унывать на путях нашей жизни. А сколько грехов мы совершаем по отношению к нашим ближним, вместе с которыми совершаем жизненный путь! Как часто мы осуждаем других людей, как часто видим лишь свои скорби, свои болезни, но не замечаем, не чувствуем, не разделяем трудности ближних, не помогаем им в несении их скорбей и болезней.

Бываем ли мы милосердны по отношению к ближним? Как часто мы замечаем и осуждаем каждый, даже малый проступок, который совершают окружающие нас люди, и в то же самое время не замечаем, что мы во много раз больше согрешаем подобным же образом. Мы не чувствуем свой грех и готовы все себе простить. В эти священные минуты следует еще и еще раз оглянуться на пройденный ранее путь, проверить свою жизнь в свете заповедей Христовых, осознать, что Господь за наши грехи принял вольные страдания, что Он претерпел Крестную смерть за спасение мира».

Святейший Патриарх Алексий II говорил о Великой Пятнице так: «Поклоняясь Живоносному Гробу Спасителя, мы должны снять вину со своего сердца, прося Господа, чтобы Он покрыл Своим милосердием наши вольные и невольные согрешения и сподобил нас радости встретить Воскресшего Господа в спасительный и светлый праздник Пасхи Христовой».

Читать также о Великой Пятнице:

- Великая Пятница: слезы Матери

- Великая Пятница: Мы рядом со Христом во время Его страданий (+видео)

- Великая Пятница. Что поется в этот день в храме

Великая Пятница. Видео по теме:

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

Дата события уникальна для каждого года. В 2023 году эта дата — 7 апреля

Великая пятница, или Страстная пятница (лат. Dies Passionis Domini) — пятница Страстной недели (последние шесть дней Великого поста, предшествующие Пасхе), которая посвящена воспоминанию осуждения на смерть, крестных страданий и смерти Иисуса Христа, а также снятию с креста Его тела и погребению Его.

Казнь распятия на кресте была самой позорной, самой мучительной и самой жестокой. Такой смертью казнили в те времена только самых отъявленных злодеев: разбойников, убийц, мятежников и преступных рабов.

Мучения распятого человека невозможно описать. Кроме нестерпимых болей во всех частях тела и страданий, распятый испытывал страшную жажду и смертельную душевную тоску.

Смерть была настолько медленная, что многие мучились на крестах по несколько дней. Даже исполнители казни — обыкновенно, люди жестокие, — не могли хладнокровно смотреть на страдания распятых. Они приготовляли питье, которым старались или утолить невыносимую жажду их, или же примесью разных веществ временно притупить сознание и облегчить муки.

По еврейскому закону, распятый на кресте считался проклятым. Начальники иудейские хотели навеки опозорить Иисуса Христа, присудив Его к такой смерти.

Когда привели Иисуса Христа на Голгофу, то воины подали Ему пить кислого вина, смешанного с горькими веществами, чтобы облегчить страдания. Но Господь, попробовав, не захотел пить его. Он не хотел употреблять никакого средства для облегчения страданий. Эти страдания Он принял на Себя добровольно за грехи людей; потому и желал перенести их до конца.

Когда все было приготовлено, воины распяли Иисуса Христа. Это было около полудня, по-еврейски в шестом часу дня. Когда же распинали Его, Он молился за Своих мучителей, говоря: «Отче! Прости им, потому что они не знают, что делают».

При кресте Спасителя стояли Матерь Его, апостол Иоанн, Мария Магдалина и еще несколько женщин, почитавших Его. Невозможно описать скорбь Божией матери, видевшей нестерпимые мучения Сына Своего!

Иисус Христос, увидев Матерь Свою и Иоанна, здесь стоящего, которого особенно любил, говорит Матери Своей: «Жено! Вот сын Твой». Потом говорит Иоанну: «Вот Матерь твоя». С этого времени Иоанн взял Матерь Божию к себе в дом и заботился о Ней до конца Ее жизни.

Между тем, во время страданий Спасителя на Голгофе произошло великое знамение. С того часа, как Спаситель был распят, то есть с шестого часа (а по нашему счету, с двенадцатого часа дня), солнце померкло и наступила тьма по всей земле, и продолжалась до самой смерти Спасителя.

Эта необычайная, всемирная тьма была отмечена языческими писателями-историками: римским астрономом Флегонтом, Фаллом и Юнием Африканом. Знаменитый философ из Афин, Дионисий Ареопагит, был в это время в Египте, в городе Гелиополе; наблюдая внезапную тьму, сказал: «Или Творец страждет, или мир разрушается». Впоследствии Дионисий Ареопагит принял христианство и был первым афинским епископом.

В ряде стран этот день является праздничным нерабочим днем, сопровождаемый различными мероприятиями и не только в церквях.

| Good Friday | |

|---|---|

A Stabat Mater depiction, 1868 |

|

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Commemoration of the crucifixion and the death of Jesus Christ |

| Celebrations | Celebration of the Passion of the Lord |

| Observances | Worship services, prayer and vigil services, fasting, almsgiving |

| Date | The Friday immediately preceding Easter Sunday |

| 2022 date |

|

| 2023 date |

|

| 2024 date |

|

| 2025 date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Passover, Christmas (which celebrates the birth of Jesus), Septuagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter, Easter Sunday (primarily), Divine Mercy Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Whit Monday, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi and Feast of the Sacred Heart which follow it. It is related to the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which focuses on the benefits, graces, and merits of the Cross, rather than Jesus’s death. |

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Holy and Great Friday), and Black Friday.[2][3][4]

Members of many Christian denominations, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist, Oriental Orthodox, United Protestant and some Reformed traditions (including certain Continental Reformed, Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches), observe Good Friday with fasting and church services.[5][6][7] In many Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist churches, the Service of the Great Three Hours’ Agony is held from noon until 3 pm, the time duration that the Bible records as darkness covering the land to Jesus’ sacrificial death on the cross.[8] Communicants of the Moravian Church have a Good Friday tradition of cleaning gravestones in Moravian cemeteries.[9]

The date of Good Friday varies from one year to the next in both the Gregorian and Julian calendars. Eastern and Western Christianity disagree over the computation of the date of Easter and therefore of Good Friday. Good Friday is a widely instituted legal holiday around the world, including in most Western countries and 12 U.S. states.[10] Some predominantly Christian countries, such as Germany, have laws prohibiting certain acts such as dancing and horse racing, in remembrance of the somber nature of Good Friday.[11][12]

Etymology[edit]

‘Good Friday’ comes from the sense ‘pious, holy’ of the word «good».[13] Less common examples of expressions based on this obsolete sense of «good» include «the good book» for the Bible, «good tide» for «Christmas» or Shrovetide, and Good Wednesday for the Wednesday in Holy Week.[14] A common folk etymology incorrectly analyzes «Good Friday» as a corruption of «God Friday» similar to the linguistically correct description of «goodbye» as a contraction of «God be with you». In Old English, the day was called «Long Friday» (langa frigedæg [ˈlɑŋɡɑ ˈfriːjedæj]), and equivalents of this term are still used in Scandinavian languages and Finnish.[15]

Other languages[edit]

In Latin, the name used by the Catholic Church until 1955 was Feria sexta in Parasceve («Friday of Preparation [for the Sabbath]»). In the 1955 reform of Holy Week, it was renamed Feria sexta in Passione et Morte Domini («Friday of the Passion and Death of the Lord»), and in the new rite introduced in 1970, shortened to Feria sexta in Passione Domini («Friday of the Passion of the Lord»).

In Dutch, Good Friday is known as Goede Vrijdag, in Frisian as Goedfreed. In German-speaking countries, it is generally referred to as Karfreitag («Mourning Friday», with Kar from Old High German kara‚ «bewail», «grieve»‚ «mourn», which is related to the English word «care» in the sense of cares and woes), but it is sometimes also called Stiller Freitag («Silent Friday») and Hoher Freitag («High Friday, Holy Friday»). In the Scandinavian languages and Finnish («pitkäperjantai»), it is called the equivalent of «Long Friday» as it was in Old English («Langa frigedæg»).

In Irish it is known as Aoine an Chéasta, «Friday of Crucifixion», from céas, «suffer;»[16] similarly, it is DihAoine na Ceusta in Scottish Gaelic.[17] In Welsh it is called Dydd Gwener y Groglith, «Friday of the Cross-Reading», referring to Y Groglith, a medieval Welsh text on the Crucifixion of Jesus that was traditionally read on Good Friday.[18]

In Greek, Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Breton and Armenian it is generally referred to as the equivalent of «Great Friday» (Μεγάλη Παρασκευή, Wielki Piątek, Nagypéntek, Vinerea Mare, Gwener ar Groaz, Ավագ Ուրբաթ). In Serbian, it is referred either Велики петак («Great Friday»), or, more commonly, Страсни петак («Loved Friday»). In Bulgarian, it is called either Велики петък («Great Friday»), or, more commonly, Разпети петък («Crucified Friday»). In French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese it is referred to as Vendredi saint, Venerdì santo, Viernes Santo and Sexta-Feira Santa («Holy Friday»), respectively. In Arabic, it is known as «الجمعة العظيمة» («Great Friday»). In Malayalam, it is called ദുഃഖ വെള്ളി («Sad Friday»).

Biblical accounts[edit]

According to the accounts in the Gospels, the royal soldiers, guided by Jesus’ disciple Judas Iscariot, arrested Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Judas received money (30 pieces of silver) [19] for betraying Jesus and told the guards that whomever he kisses is the one they are to arrest. Following his arrest, Jesus was taken to the house of Annas, the father-in-law of the high priest, Caiaphas. There he was interrogated with little result and sent bound to Caiaphas the high priest where the Sanhedrin had assembled.[20]

Conflicting testimony against Jesus was brought forth by many witnesses, to which Jesus answered nothing. Finally the high priest adjured Jesus to respond under solemn oath, saying «I adjure you, by the Living God, to tell us, are you the Anointed One, the Son of God?» Jesus testified ambiguously, «You have said it, and in time you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Almighty, coming on the clouds of Heaven.» The high priest condemned Jesus for blasphemy, and the Sanhedrin concurred with a sentence of death.[21] Peter, waiting in the courtyard, also denied Jesus three times to bystanders while the interrogations were proceeding just as Jesus had foretold.

In the morning, the whole assembly brought Jesus to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate under charges of subverting the nation, opposing taxes to Caesar, and making himself a king.[22] Pilate authorized the Jewish leaders to judge Jesus according to their own law and execute sentencing; however, the Jewish leaders replied that they were not allowed by the Romans to carry out a sentence of death.[23]

Pilate questioned Jesus and told the assembly that there was no basis for sentencing. Upon learning that Jesus was from Galilee, Pilate referred the case to the ruler of Galilee, King Herod, who was in Jerusalem for the Passover Feast. Herod questioned Jesus but received no answer; Herod sent Jesus back to Pilate. Pilate told the assembly that neither he nor Herod found Jesus to be guilty; Pilate resolved to have Jesus whipped and released.[24] Under the guidance of the chief priests, the crowd asked for Barabbas, who had been imprisoned for committing murder during an insurrection. Pilate asked what they would have him do with Jesus, and they demanded, «Crucify him»[25] Pilate’s wife had seen Jesus in a dream earlier that day, and she forewarned Pilate to «have nothing to do with this righteous man».[26] Pilate had Jesus flogged and then brought him out to the crowd to release him. The chief priests informed Pilate of a new charge, demanding Jesus be sentenced to death «because he claimed to be God’s son.» This possibility filled Pilate with fear, and he brought Jesus back inside the palace and demanded to know from where he came.[27]

Coming before the crowd one last time, Pilate declared Jesus innocent and washed his own hands in water to show he had no part in this condemnation. Nevertheless, Pilate handed Jesus over to be crucified in order to forestall a riot.[28] The sentence written was «Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.» Jesus carried his cross to the site of execution (assisted by Simon of Cyrene), called the «place of the Skull», or «Golgotha» in Hebrew and in Latin «Calvary». There he was crucified along with two criminals.[29]

Jesus agonized on the cross for six hours. During his last three hours on the cross, from noon to 3 pm, darkness fell over the whole land.[30] Jesus spoke from the cross, quoting the messianic Psalm 22: «My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?»

With a loud cry, Jesus gave up his spirit. There was an earthquake, tombs broke open, and the curtain in the Temple was torn from top to bottom. The centurion on guard at the site of crucifixion declared, «Truly this was God’s Son!»[31]

Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin and a secret follower of Jesus, who had not consented to his condemnation, went to Pilate to request the body of Jesus[32] Another secret follower of Jesus and member of the Sanhedrin named Nicodemus brought about a hundred-pound weight mixture of spices and helped wrap the body of Jesus.[33] Pilate asked confirmation from the centurion of whether Jesus was dead.[34] A soldier pierced the side of Jesus with a lance causing blood and water to flow out[35] and the centurion informed Pilate that Jesus was dead.[36]

Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus’ body, wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and placed it in his own new tomb that had been carved in the rock[37] in a garden near the site of the crucifixion. Nicodemus[38] also brought 75 pounds of myrrh and aloes, and placed them in the linen with the body, in keeping with Jewish burial customs[33] They rolled a large rock over the entrance of the tomb.[39] Then they returned home and rested, because Shabbat had begun at sunset.[40] Matt. 28:1 «After the Shabbat, at dawn on the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to look at the tomb». i.e. «After the Sabbath, at dawn on the first day of the week,…». «He is not here; he has risen, just as he said….». (Matt. 28:6)

Orthodox[edit]

Byzantine Christians (Eastern Christians who follow the Rite of Constantinople: Orthodox Christians and Greek-Catholics) call this day «Great and Holy Friday», or simply «Great Friday».[41] Because the sacrifice of Jesus through his crucifixion is recalled on this day, the Divine Liturgy (the sacrifice of bread and wine) is never celebrated on Great Friday, except when this day coincides with the Great Feast of the Annunciation, which falls on the fixed date of 25 March (for those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, 25 March currently falls on 7 April of the modern Gregorian Calendar). Also on Great Friday, the clergy no longer wear the purple or red that is customary throughout Great Lent,[42] but instead don black vestments. There is no «stripping of the altar» on Holy and Great Thursday as in the West; instead, all of the church hangings are changed to black, and will remain so until the Divine Liturgy on Great Saturday.

The faithful revisit the events of the day through the public reading of specific Psalms and the Gospels, and singing hymns about Christ’s death. Rich visual imagery and symbolism, as well as stirring hymnody, are remarkable elements of these observances. In the Orthodox understanding, the events of Holy Week are not simply an annual commemoration of past events, but the faithful actually participate in the death and the resurrection of Jesus.

Each hour of this day is the new suffering and the new effort of the expiatory suffering of the Savior. And the echo of this suffering is already heard in every word of our worship service – unique and incomparable both in the power of tenderness and feeling and in the depth of the boundless compassion for the suffering of the Savior. The Holy Church opens before the eyes of believers a full picture of the redeeming suffering of the Lord beginning with the bloody sweat in the Garden of Gethsemane up to the crucifixion on Golgotha. Taking us back through the past centuries in thought, the Holy Church brings us to the foot of the cross of Christ erected on Golgotha and makes us present among the quivering spectators of all the torture of the Savior.[43]

Great and Holy Friday is observed as a strict fast, also called the Black Fast, and adult Byzantine Christians are expected to abstain from all food and drink the entire day to the extent that their health permits. «On this Holy day neither a meal is offered nor do we eat on this day of the crucifixion. If someone is unable or has become very old [or is] unable to fast, he may be given bread and water after sunset. In this way we come to the holy commandment of the Holy Apostles not to eat on Great Friday.»[43]

Matins of Holy and Great Friday[edit]

The Byzantine Christian observance of Holy and Great Friday, which is formally known as The Order of Holy and Saving Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ, begins on Thursday night with the Matins of the Twelve Passion Gospels. Scattered throughout this Matins service are twelve readings from all four of the Gospels which recount the events of the Passion from the Last Supper through the Crucifixion and burial of Jesus. Some churches have a candelabrum with twelve candles on it, and after each Gospel reading one of the candles is extinguished.[44]

The first of these twelve readings[45] is the longest Gospel reading of the liturgical year, and is a concatenation from all four Gospels. Just before the sixth Gospel reading, which recounts Jesus being nailed to the cross, a large cross is carried out of the sanctuary by the priest, accompanied by incense and candles, and is placed in the center of the nave (where the congregation gathers) Sēmeron Kremātai Epí Xýlou:

Today He who hung the earth upon the waters is hung upon the Cross (three times).

He who is King of the angels is arrayed in a crown of thorns.

He who wraps the Heavens in clouds is wrapped in the purple of mockery.

He who in Jordan set Adam free receives blows upon His face.

The Bridegroom of the Church is transfixed with nails.

The Son of the Virgin is pierced with a spear.

We venerate Thy Passion, O Christ (three times).

Show us also Thy glorious Resurrection.[46][47]

The readings are:

- John 13:31-18:1 – Christ’s last sermon, Jesus prays for the apostles.

- John 18:1–28 – The agony in the garden, the mockery and denial of Christ.

- Matthew 26:57–75 – The mockery of Christ, Peter denies Christ.

- John 18:28–19:16 – Pilate questions Jesus; Jesus is condemned; Jesus is mocked by the Romans.

- Matthew 27:3–32 – Judas commits suicide; Jesus is condemned; Jesus mocked by the Romans; Simon of Cyrene compelled to carry the cross.

- Mark 15:16–32 – Jesus dies.

- Matthew 27:33–54 – Jesus dies.

- Luke 23:32–49 – Jesus dies.

- John 19:25–37 – Jesus dies.

- Mark 15:43–47 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- John 19:38–42 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- Matthew 27:62–66 – The Jews set a guard.

During the service, all come forward to kiss the feet of Christ on the cross. After the Canon, a brief, moving hymn, The Wise Thief is chanted by singers who stand at the foot of the cross in the center of the nave. The service does not end with the First Hour, as usual, but with a special dismissal by the priest:

May Christ our true God, Who for the salvation of the world endured spitting, and scourging, and buffeting, and the Cross, and death, through the intercessions of His most pure Mother, of our holy and God-bearing fathers, and of all the saints, have mercy on us and save us, for He is good and the Lover of mankind.

Royal Hours[edit]

Vigil during the Service of the Royal Hours

The next day, in the forenoon on Friday, all gather again to pray the Royal Hours,[48] a special expanded celebration of the Little Hours (including the First Hour, Third Hour, Sixth Hour, Ninth Hour and Typica) with the addition of scripture readings (Old Testament, Epistle and Gospel) and hymns about the Crucifixion at each of the Hours (some of the material from the previous night is repeated). This is somewhat more festive in character, and derives its name of «Royal» from both the fact that the Hours are served with more solemnity than normal, commemorating Christ the King who humbled himself for the salvation of mankind, and also from the fact that this service was in the past attended by the Emperor and his court.[49]

Vespers of Holy and Great Friday[edit]

In the afternoon, around 3 pm, all gather for the Vespers of the Taking-Down from the Cross,[50] commemorating the Deposition from the Cross. Following Psalm 103 (104) and the Great Litany, ‘Lord, I call’ is sung without a Psalter reading. The first five stichera (the first being repeated) are taken from the Aposticha at Matins the night before, but the final 3 of the 5 are sung in Tone 2. Three more stichera in Tone 6 lead to the Entrance. The Evening Prokimenon is taken from Psalm 21 (22): ‘They parted My garments among them, and cast lots upon My vesture.’

There are then four readings, with Prokimena before the second and fourth:

- Exodus 33:11-23 — God shows Moses His glory

- The second Prokimenon is from Psalm 34 (35): ‘Judge them, O Lord, that wrong Me: fight against them that fight against Me.’

- Job 42:12-20 — God restores Job’s wealth (note that verses 18-20 are found only in the Septuagint)

- Isaiah 52:13-54:1 — The fourth Suffering Servant song

- The third Prokimenon is from Psalm 87 (88): ‘They laid Me in the lowest pit: in dark places and in the shadow of death.’

- 1 Corinthians 1:18-2:2 — St. Paul places Christ crucified as the centre of the Christian life

An Alleluia is then sung, with verses from Psalm 68 (69): ‘Save Me, O God: for the waters are come in, even unto My soul.’

The Gospel reading is a composite taken from three of the four the Gospels (Matthew 27:1-38; Luke 23:39-43; Matthew 27:39-54; John 19:31-37; Matthew 27:55-61), essentially the story of the Crucifixion as it appears according to St. Matthew, interspersed with St. Luke’s account of the confession of the Good Thief and St. John’s account of blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side. During the Gospel, the body of Christ (the soma) is removed from the cross, and, as the words in the Gospel reading mention Joseph of Arimathea, is wrapped in a linen shroud, and taken to the altar in the sanctuary.

The epitaphios («winding sheet»), depicting the preparation of the body of Jesus for burial

The Aposticha reflects on the burial of Christ. Either at this point (in the Greek use) or during the troparion following (in the Slav use):

Noble Joseph, taking down Thy most pure body from the Tree, wrapped it in pure linen and spices, and he laid it in a new tomb.[51]

an epitaphios or «winding sheet» (a cloth embroidered with the image of Christ prepared for burial) is carried in procession to a low table in the nave which represents the Tomb of Christ; it is often decorated with an abundance of flowers. The epitaphios itself represents the body of Jesus wrapped in a burial shroud, and is a roughly full-size cloth icon of the body of Christ. The service ends with a hope of the Resurrection:

The Angel stood by the tomb, and to the women bearing spices he cried aloud: ‘Myrrh is fitting for the dead, but Christ has shown Himself a stranger to corruption.[51]

Then the priest may deliver a homily and everyone comes forward to venerate the epitaphios. In the Slavic practice, at the end of Vespers, Compline is immediately served, featuring a special Canon of the Crucifixion of our Lord and the Lamentation of the Most Holy Theotokos by Symeon the Logothete.[52]

Matins of Holy and Great Saturday[edit]

The Epitaphios being carried in procession in a church in Greece.

On Friday night, the Matins of Holy and Great Saturday, a unique service known as The Lamentation at the Tomb[53] (Epitáphios Thrēnos) is celebrated. This service is also sometimes called Jerusalem Matins. Much of the service takes place around the tomb of Christ in the center of the nave.[54]

Epitaphios adorned for veneration, Church of Saints Constantine and Helen, Hippodromion Sq., Thessaloniki, Greece (Good Friday 2022).

A unique feature of the service is the chanting of the Lamentations or Praises (Enkōmia), which consist of verses chanted by the clergy interspersed between the verses of Psalm 119 (which is, by far, the longest psalm in the Bible). The Enkōmia are the best-loved hymns of Byzantine hymnography, both their poetry and their music being uniquely suited to each other and to the spirit of the day. They consist of 185 tercet antiphons arranged in three parts (stáseis or «stops»), which are interjected with the verses of Psalm 119, and nine short doxastiká («Gloriae») and Theotókia (invocations to the Virgin Mary). The three stáseis are each set to its own music, and are commonly known by their initial antiphons: Ἡ ζωὴ ἐν τάφῳ, «Life in a grave», Ἄξιον ἐστί, «Worthy it is», and Αἱ γενεαὶ πᾶσαι, «All the generations». Musically they can be classified as strophic, with 75, 62, and 48 tercet stanzas each, respectively. The climax of the Enkōmia comes during the third stásis, with the antiphon «Ō glyký mou Éar«, a lamentation of the Virgin for her dead Child («O, my sweet spring, my sweetest child, where has your beauty gone?»). Later, during a different antiphon of that stasis («Early in the morning the myrrh-bearers came to Thee and sprinkled myrrh upon Thy tomb»), young girls of the parish place flowers on the Epitaphios and the priest sprinkles it with rose-water. The author(s) and date of the Enkōmia are unknown. Their High Attic linguistic style suggests a dating around the 6th century, possibly before the time of St. Romanos the Melodist.[55]

The Epitaphios mounted upon return of procession, at an Orthodox Church in Adelaide, Australia.

The Evlogitaria (Benedictions) of the Resurrection are sung as on Sunday, since they refer to the conversation between the myrrh-bearers and the angel in the tomb, followed by kathismata about the burial of Christ. Psalm 50 (51) is then immediately read, and then followed by a much loved-canon, written by Mark the Monk, Bishop of Hydrous and Kosmas of the Holy City, with irmoi by Kassiani the Nun. The high-point of the much-loved Canon is Ode 9, which takes the form of a dialogue between Christ and the Theotokos, with Christ promising His Mother the hope of the Resurrection. This Canon will be sung again the following night at the Midnight Office.

Lauds follows, and its stichera take the form of a funeral lament, while always preserving the hope of the Resurrection. The doxasticon links Christ’s rest in the tomb with His rest on the seventh day of creation, and the theotokion («Most blessed art thou, O Virgin Theotokos…) is the same as is used on Sundays.

At the end of the Great Doxology, while the Trisagion is sung, the epitaphios is taken in procession around the outside the church, and is then returned to the tomb. Some churches observe the practice of holding the epitaphios at the door, above waist level, so the faithful most bow down under it as they come back into the church, symbolizing their entering into the death and resurrection of Christ. The epitaphios will lay in the tomb until the Paschal Service early Sunday morning. In some churches, the epitaphios is never left alone, but is accompanied 24 hours a day by a reader chanting from the Psalter.[citation needed]

When the procession has returned to the church, a troparion is read, similar to hthe ones read at the Sixth Hour throughout Lent, focusing on the purpose of Christ’s burial. A series of prokimena and readings are then said:

- The first prokimenon is from Psalm 43 (44): ‘Arise, Lord, and help us: and deliver us for Thy Name’s sake.’

- Ezekiel 37:1-14 — God tells Ezekiel to command bones to come to life.

- The second prokimenon is from Psalm 9 (9-10), and is based on the verses sung at the kathismata and Lauds on Sundays: ‘Arise, O Lord my God, lift up Thine hand: forget not Thy poor forever.’

- 1 Corinthians 5:6-8; Galatians 3:13-14 — St. Paul celebrates the Passion of Christ and explains its role in the life of Gentile Christians.

- The Alleluia verses are from Psalm 67 (68), and are based on the Paschal verses: ‘Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered.’

- Matthew 27:62-66 — The Pharisees ask Pilate to set a watch at the tomb.

At the end of the service, a final hymn is sung as the faithful come to venerate the Epitaphios.

Roman Catholic[edit]

Day of Fasting[edit]

The Catholic Church regards Good Friday and Holy Saturday as the Paschal fast, in accordance with Article 110 of Sacrosanctum Concilium.[56] In the Latin Church, a fast day is understood as having only one full meal and two collations (a smaller repast, the two of which together do not equal the one full meal)[57][58] – although this may be observed less stringently on Holy Saturday than on Good Friday.[56]

Services on the day[edit]

The Roman Rite has no celebration of Mass between the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday evening and the Easter Vigil unless a special exemption is granted for rare solemn or grave occasions by the Vatican or the local bishop. The only sacraments celebrated during this time are Baptism (for those in danger of death), Penance, and Anointing of the Sick.[59] While there is no celebration of the Eucharist, it is distributed to the faithful only in the Celebration of the Lord’s Passion, but can also be taken at any hour to the sick who are unable to attend this celebration.[60]

The Celebration of the Passion of the Lord takes place in the afternoon, ideally at three o’clock; however, for pastoral reasons (especially in countries where Good Friday is not a public holiday), it is permissible to celebrate the liturgy earlier,[61] even shortly after midday, or at a later hour.[62] The celebration consists of three parts: the liturgy of the word, the adoration of the cross, and the Holy communion.[63] he altar is bare, without cross, candlesticks and altar cloths.[64] It is also customary to empty the holy water fonts in preparation of the blessing of the water at the Easter Vigil.[65] Traditionally, no bells are rung on Good Friday or Holy Saturday until the Easter Vigil.[66]

The liturgical colour of the vestments used is red.[67] Before 1970, vestments were black except for the Communion part of the rite when violet was used.[68] If a bishop or abbot celebrates, he wears a plain mitre (mitra simplex).[69] Before the reforms of the Holy Week liturgies in 1955, black was used throughout.

The Vespers of Good Friday are only prayed by those who could not attend the Celebration of the Passion of the Lord.[70]

Three Hours’ Agony[edit]

The Three Hours’ Devotion based on the Seven Last Words from the Cross begins at noon and ends at 3 pm, the time that the Christian tradition teaches that Jesus died on the cross.[71]

Liturgy[edit]

The Good Friday liturgy consists of three parts: the Liturgy of the Word, the Veneration of the Cross, and the Holy Communion.

- The Liturgy of the Word consists of the clergy and assisting ministers entering in complete silence, without any singing. They then silently make a full prostration. This signifies the abasement (the fall) of (earthly) humans.[72] It also symbolizes the grief and sorrow of the Church.[73] Then follows the Collect prayer, and the reading or chanting of Isaiah 52:13–53:12, Hebrews 4:14–16, Hebrews 5:7–9, and the Passion account from the Gospel of John, traditionally divided between three deacons,[74] yet usually read by the celebrant and two other readers. In the older form of the Mass known as the Tridentine Mass the readings for Good Friday are taken from Exodus 12:1-11 and the Gospel according to St. John (John 18:1-40); (John 19:1-42).

- The Great Intercessions also known as orationes sollemnes immediately follows the Liturgy of the Word and consists of a series of prayers for the Church, the Pope, the clergy and laity of the Church, those preparing for baptism, the unity of Christians, the Jews, those who do not believe in Christ, those who do not believe in God, those in public office, and those in special need.[75] After each prayer intention, the deacon calls the faithful to kneel for a short period of private prayer; the celebrant then sums up the prayer intention with a Collect-style prayer. As part of the pre-1955 Holy Week Liturgy, the kneeling was omitted only for the prayer for the Jews.[76]

- The Adoration of the Cross has a crucifix, not necessarily the one that is normally on or near the altar at other times of the year, solemnly unveiled and displayed to the congregation, and then venerated by them, individually if possible and usually by kissing the wood of the cross, while hymns and the Improperia («Reproaches») with the Trisagion hymn are chanted.[77]

- Holy Communion is bestowed according to a rite based on that of the final part of Mass, beginning with the Lord’s Prayer, but omitting the ceremony of «Breaking of the Bread» and its related acclamation, the Agnus Dei. The Eucharist, consecrated at the Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday, is distributed at this service.[78] Before the Holy Week reforms of Pope Pius XII in 1955, only the priest received Communion in the framework of what was called the Mass of the Presanctified, which included the usual Offertory prayers, with the placing of wine in the chalice, but which omitted the Canon of the Mass.[76] The priest and people then depart in silence, and the altar cloth is removed, leaving the altar bare except for the crucifix and two or four candlesticks.[79]

Stations of the Cross[edit]

Rome: canopy erected at the «Temple of Venus and Rome» during the «Way of the Cross» ceremony

In addition to the prescribed liturgical service, the Stations of the Cross are often prayed either in the church or outside, and a prayer service may be held from midday to 3.00 pm, known as the Three Hours’ Agony. In countries such as Malta, Italy, Philippines, Puerto Rico and Spain, processions with statues representing the Passion of Christ are held.[citation needed]

In Rome, since the papacy of John Paul II, the heights of the Temple of Venus and Roma and their position opposite the main entrance to the Colosseum have been used to good effect as a public address platform. This may be seen in the photograph below where a red canopy has been erected to shelter the Pope as well as an illuminated cross, on the occasion of the Way of the Cross ceremony. The Pope, either personally or through a representative, leads the faithful through meditations on the stations of the cross while a cross is carried from there to the Colosseum.[80]