From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A Diablada dance squad passing through the streets during the Oruro Carnival in Bolivia. |

|

| Genre | Folk dance |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Pre-Columbian Andean civilizations |

| Year | 1500s |

| Origin | Altiplano region, South America |

The Diablada, also known as the Danza de los Diablos (English: Dance of the Devils), is an Andean folk dance performed in the Altiplano region of South America, characterized by performers wearing masks and costumes representing the devil and other characters from pre-Columbian theology and mythology.[1][2] combined with Spanish and Christian elements added during the colonial era. Many scholars have concluded that the dance is descended from the Llama llama dance in honor of the Uru god Tiw,[3] and the Aymaran ritual to the demon Anchanchu, both originating in pre-Columbian Bolivia,[4][5] though there are competing theories on the dance’s origins.

While the dance had been performed in the Andean region as early as the 1500s, its name originated in 1789 in Orouro, Bolivia, where performers dressed like the devil in parades called Diabladas. The first organized Diablada group with defined music and choreography appeared in Bolivia in 1904.[2][6] There is also some evidence of the dance originating among miners in Potosi, Bolivia,[7] while regional dances in Peru and Chile may have also influenced the modern version.

History[edit]

Pre-Columbian origins[edit]

Bolivian historians claim that the Diablada originated in that country, and that Oruro should be named as its place of origin under the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity policy promoted by UNESCO; Bolivia has also claimed that performances of the dance in other countries are cultural appropriation.[8][9] Bolivian historians currently maintain that the Diablada dates back 2000 years to the rituals of the Uru civilization dedicated to the mythological figure Tiw, who protected caves, lakes, and rivers as places of shelter. The dance is believed to have originated as the Llama llama in the ancient settlement of Oruro, which was one of the major centers of the Uru civilization.[10][11] The dance includes references to animals that appear in Uru mythology such as ants, lizards, toads, and snakes.[12][13][14] Bolivian anthropologist Milton Eyzaguirre adds that the ancient cultures of the Bolivian Andes practiced a death cult called cupay, with that term eventually evolving into supay or the devil figure in the modern Diablada.[15]

Due to syncretism caused by Spanish influence in later centuries, Tiw was eventually associated with the devil; Spanish authorities also outlawed several of the ancient traditions but incorporated others into Christian theology.[16] Local and regional Diablada festivals arose during the Spanish colonial period and were eventually consolidated as the Carnaval de Oruro in the modern city of that name.[10]

…The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro….

— Proclamation of «Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity» to the «Carnival of Oruro», UNESCO 2001

Chilean and Peruvian organizations suggest that since the dance has roots in Andean civilizations that existed before the formation of the current national borders, it should belong equally to the three nations.[17] Some Chilean historians concede that the Diablada originated in Bolivia and was adopted for Chile’s Fiesta de La Tirana in 1952, though it is also influenced by a similar 16th Century Chilean tradition called Diablos sueltos.[18]

Some Peruvian historians also concede that the dance originated in Bolivia but was influenced by earlier traditions practiced across the Altiplano region, including some specific to Peru.[19][20] The Peruvian version, Diablada puneña, originated in the late 1500s among the Lupaka people in the Puno region, who in turn were influenced by the Jesuits; with that dance merging with the Bolivian version in the early 1900s.[21][22] Scholars who defend the Diablada’s origins in Peru cite Aymaran traditions surrounding the deity Anchanchu that had been documented by 16th Century historian Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.[4][23] There is also a version of the Diablada in Ecuador called the Diablada pillareña.[24]

Spanish influence[edit]

Some historians have theorized that the modern Diablada exhibits influences from Spanish dance traditions. In her book La danza de los diablos, Julia Elena Fortún proposed a connection with the Catalan entremés called Ball de diables as performed in the Catalonian communities of Penedès and Tarragona. That dance depicts a struggle between Lucifer and the archangel Saint Michael and is first known to have been performed in 1150.[25][26] Catalan scholar Jordi Rius i Mercade has also found similarities between the Ball de diables and several Andean dances including the similarly-themed Baile de Diablos de Cobán in Guatemala and Danza de los diablicos de Túcume in Peru.[25]

Those theories contradict the more common theory that the modern Diablada is most influenced by the Spanish practice of autos sacramentales during which the colonizers introduced Christianity to the natives of the Andes, due to differing conceptions of the devil and his temptations.[27] The autos sacramentales process has been cited as an influence on the emergence of the Diablada puneña in Peru, shortly after the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, as believed by Garcilaso de la Vega.[28] Peruvian scholar Nicomedes Santa Cruz and Bolivian anthropologist Freddy Arancibia Andrade have suggested a similar process, with the dance originating among miners who rebelled against the Spanish at Potosi in 1538 while combining the ancient ritual of Tinku with Christian references.[7][29] Andrade has also proposed a similar process among striking miners in 1904 as the origin of the modern version of the Diablada.[7]

Post-independence period[edit]

Though the traditions of the Diablada were merged with Christianity during the colonial period, the meanings of the original traditions were revived and reassessed during the Latin American wars of independence. The Altiplano region, particularly around Lake Titicaca, became a center of appreciation for pre-Columbian dance and music.[30] During the Bolivian War of Independence, the main religious festival honoring the Virgin of the Candlemas was replaced by Carnival, which allowed for greater acknowledgement of pre-Christian traditions including the Diablada. The present annual Diablada festival was established in Oruro by 1891.[31]

The first institutionalized Diablada dance squad was the Gran Tradicional y Auténtica Diablada Oruro, founded in Bolivia in 1904 by Pedro Pablo Corrales.[32] That squad established a counterpart called the Los Vaporinos in Peru in 1918.[33] A squad from Bolivia was invited to travel to the Fiesta de la Tirana in Chile in 1956, and that country’s first established squad was called Primera Diablada Servidores Virgen del Carmen, centered in Iquique.[34] In 2001, the Carnaval de Oruro was declared one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, along with the Diablada and 19 other dances performed at the festival.[35] In 2004, the Bolivian government awarded high national honors to the Gran Tradicional y Auténtica Diablada Oruro for its 100th anniversary.[36]

Choreography[edit]

Diablada dancers in Puno, Peru.

In its original form, the dance was performed with music by a band of Sikuris, who played the siku. In modern times the dance is accompanied by an orchestra. Dancers often perform on streets and public squares, but the ritual can also be performed at indoor theaters and arenas. The ritual begins with a krewe featuring Lucifer and Satan with several China Supay, or devil women. They are followed by the personified seven deadly sins of pride, greed, lust, anger, gluttony, envy, and sloth. Afterwards, a troop of devils come out. They are all led by Saint Michael, with a blouse, short skirt, sword, and shield. During the dance, angels and demons move continuously. This confrontation between the two sides is eclipsed when Saint Michael appears and defeats the Devil. The choreography has three versions, each consisting of seven moves.[37]

Music[edit]

The music associated with the dance has two parts: the first is known as the March and the second one is known as the Devil’s Mecapaqueña. Some squads play only one melody or start the Mecapaqueña in the fourth movement «by four».[37] Since the second half of the 20th century, dialogue is omitted so the focus is only on the dance.[38]

Regional variations[edit]

Diablada Puneña (Peru)[edit]

The Diablada Puneña originated in modern Peru with the in the Lupaka people in 1576, when they combined tenets of Christianity from the autos sacramentales with ancient Aymara traditions.[4][23] Some additional influences from the cult of the Virgin Mary were added in the following century.[22] The Peruvian version of the Diablada was quite different from the Ururo-based Bolivian version until the two merged at the Fiesta de la Candelaria in 1965. However, the Peruvian versions continue to feature homegrown figures like Superman, American Indians, ancient Mexicans, and characters from popular films.[39]

The costumes used in the Peruvian Diablata also include influences from Tibet as well as elements from pre-Columbian Peruvian cultures such as Sechin, Chavin, Nazca, and Mochica.[4] Homegrown masks were produced and sold in Peru starting in 1956.[40] Music for the dance was originally performed on the siku,[41] but that was later replaced by percussionists known as Sicu-Morenos.[39]

Fiesta de La Tirana (Chile)[edit]

In Chile, the Diablada is performed during the Fiesta de La Tirana in the northern region of that country. The festival attracts more than 100,000 visitors annually to the small village of La Tirana.[42] The festival is descended from the celebrations for the Virgin of Carmen that began in 1540.[42]

See also[edit]

- Carnaval de Oruro

- Fiesta de la Candelaria

- Fiesta de La Tirana

References[edit]

- ^ Kartomi, Margaret J.; Blum, Stephen (1994). Music-cultures in Contact: Convergences and Collisions. p. 63. ISBN 9782884491372.

- ^ a b Real Academia Española (2001). «Diccionario de la Lengua Española – Vigésima segunda edición» [Spanish Language Dictionary — 22nd edition] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

Danza típica de la región de Oruro, en Bolivia, llamada así por la careta y el traje de diablo que usan los bailarines (Typical dance from the region of Oruro, in Bolivia, called that way by the mask and devil suit worn by the dancers).

- ^ «Bolivia (Plurinational State of) — Information related to Intangible Cultural Heritage». UNESCO. 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

The town of Oruro, situated at an altitude of 3,700 metres in the mountains of western Bolivia and once a pre-Columbian ceremonial site, was an important mining area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Resettled by the Spanish in 1606, it continued to be a sacred site for the Uru people, who would often travel long distances to perform their rituals, especially for the principal Ito festival. The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro.

- ^ a b c d Rubio Zapata, Miguel (Fall 2007). «Diablos Danzantes en Puno, Perú» [Dancing devils in Puno, Peru]. ReVista, Harvard Review of Latin America (in Spanish). VII (1): 66–67. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Morales Serruto, José (3 August 2009). «La diablada, manzana de la discordia en el altiplano [The »Diablada», the bone of contention in the Altiplano]» (Interview) (in Spanish). Puno, Peru: Correo. Retrieved 27 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://www.carnavaldeoruroacfo.com/documentos/FORMULARIO%20DE%20CANDIDATURA.pdf Archived 2009-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Compilation of historians, anthropologists, researchers and folklorists about the Carnival of Oruro and La Diablada

- ^ a b c Arancibia Andrade, Freddy (20 August 2009). «Investigador afirma que la diablada surgió en Potosí [Investigator affirms that the »Diablada» emerged in Potosí]» (Interview) (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ «Perú dice que la diablada no es exclusiva de Bolivia» [Peru says that the Diablada is not exclusive of Bolivia]. La Prensa (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: Editores Asociados S.A. 14 August 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Echevers Tórrez 2009

- ^ a b A.C.F, O. 2001, pp.10-17.

- ^ Guaman Poma de Ayala 1615, p.235.

- ^ Claure Covarrubias, Javier (January 2009). «El Tío de la mina» [The Uncle of the mine] (in Spanish). Stockholm, Sweden: Arena y Cal, revista literaria y cultural divulgativa. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Ríos, Edwin (2009). «Mitología andina de los urus» [Andean mythology of the Urus]. Mi Carnaval (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Ríos, Edwin (2009). «La Diablada originada en Oruro – Bolivia» [The Diablada originated in Oruro – Bolivia]. Mi Carnaval (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ «La diablada orureña se remonta a la época de los Urus precoloniales» [The Diablada of Oruro goes back to the times of the Pre-Columbian Urus]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. 9 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ A.C.F, O. 2001, p.3.

- ^ Moffett, Matt; Kozak, Robert (21 August 2009). «In This Spat Between Bolivia and Peru, The Details Are in the Devils». The Wall Street Journal. p. A1. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Memoria Chilena diabladas» (in Spanish).

- ^ Américo Valencia Chacon. «Candelaria una propuesta frente a una gran responsabilidad» (in Spanish).

- ^ Luis Valverde Caldas. «La diablada como danza» (in Spanish).

- ^ Cuentas Ormachea 1986, pp. 35–36, 45.

- ^ a b Morales Serruto, José (3 August 2009). «La diablada, manzana de la discordia en el altiplano [The »Diablada», the bone of contention in the Altiplano]» (Interview) (in Spanish). Puno, Peru: Correo. Retrieved 27 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b McFarren, Peter; Choque, Sixto; Gisbert, Teresa (2009) [1993]. McFarren, Peter (ed.). Máscaras de los Andes bolivianos [Masks of the Bolivian Andes] (in Spanish). Indiana, United States: Editorial Quipus. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ «Municipio realiza actualización del avalúo para el bienio 2016-2017». Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ a b Rius I Mercade 2005

- ^ Fortún 1961, p. 23.

- ^ Fortún 1961, p. 24.

- ^ De la Vega, Garcilaso; Serna, Mercedes (2000) [1617]. «XXVIII». Comentarios Reales [Royal Commentaries]. Clásicos Castalia (in Spanish). Vol. 252 (2000 ed.). Madrid, Spain: Editorial Castalia. pp. 226–227. ISBN 84-7039-855-5. OCLC 46420337.

- ^ Santa Cruz, 2004, p. 285.

- ^ Salles-Reese 1997, pp. 166-167.

- ^ Harris 2003, pp. 205-211.

- ^ «La diablada orureña se remonta a la época de los Urus precoloniales» [The Diablada of Oruro goes back to the times of the Pre-Columbian Urus]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. 9 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Cuentas Ormachea 1986, pp. 35–36, 45.

- ^ «El folclor de Chile y sus tres grandes raíces» [The Chile’s folklore and its three great roots] (in Spanish). Memorias Chilenas. 2004. Archived from the original on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ «Bolivia (Plurinational State of) — Information related to Intangible Cultural Heritage». UNESCO. 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

The town of Oruro, situated at an altitude of 3,700 metres in the mountains of western Bolivia and once a pre-Columbian ceremonial site, was an important mining area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Resettled by the Spanish in 1606, it continued to be a sacred site for the Uru people, who would often travel long distances to perform their rituals, especially for the principal Ito festival. The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro.

- ^ «La Diablada De Oruro, máscara danza pagana» [The Diablada of Oruro, mask pagan dance] (in Spanish). 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ a b Fortún, Julia Elena (1961). «Actual coreografía del baile de los diablos» [Current choreography of the devils dance]. La danza de los diablos [The dance of the devils] (DOC). Autores bolivianos contemporáneos (in Spanish). Vol. 5. La Paz, Bolivia: Ministerio de Educación y Bellas Artes, Oficialía Mayor de Cultura Nacional. OCLC 3346627.

- ^ Gisbert 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Cuentas Ormachea, Enrique (23 August 2009). «Diablada: coreografía, vestimenta y música» [Diablada: choreography, clothing and music]. Los Andes (in Spanish). Puno, Peru. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Jiménez Borja, Arturo (1996). Fundación del Banco Continental para el Fomento de la Educación y la Cultura (ed.). Máscaras peruanas [Peruvian masks] (in Spanish). Lima, Peru. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore (Bolivia) (2003). MUSEF (ed.). Serie anales de la reunión anual de etnología [Records of the annual reunion of ethnology series] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. La Paz, Bolivia: MUSEF. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ a b «Danzas ceremoniales del área cultural del Norte» [Ceremonial dances of the northern cultural area] (in Spanish). Chile: Hamaycan. Archived from the original on June 9, 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

Articles:

- Eckels, Charlene (17 October 2013). «Dance of the Devils» [Dance of the Devils]. Yareah. New York, New York. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Cajías, Fernando (23 August 2009). «La diablada orureña ya era noticia en el siglo XIX» [The Diablada of Oruro was already news in the 19th century]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Cuentas Ormachea, Enrique (March 1986). «La Diablada: Una expresión de coreografía mestiza del Altiplano del Collao» [The Diablada: A mixed race choreographic expression of the Altiplano in the Collao]. Boletín de Lima (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Editorial Los Pinos. year 8 (44). ISSN 0253-0015. Archived from the original (PNG) on June 16, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- Echevers Tórrez, Diego (3 October 2009). «Sobre diablos y diabladas, A propósito de apreciaciones sesgadas» [About devils and Diabladas, speaking about biased interpretations]. La Patria (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Gisbert, Teresa (December 2002). «El control de lo imaginario: teatralización de la fiesta» [The control of the imaginary: theatralization of the party] (PDF). Módulo: Estudios de caso – Session 14, Lecture 3 (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- Rius i Mercade, Jordi (18 January 2008). «Concomitàncies entre els balls de diables catalans i les diabladas d’Amèrica del Sud» [Concomitances between the Ball de diables and the Diabladas of South America] (in Catalan). Tarragona, Spain: Junta del Ball de Diables www.balldediables.org. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Thomas M Landy, «Dancing for the Virgin at La Tirana», Catholics & Cultures updated February 17, 2017

Books

- Asociación de Conjuntos del Folklore de Oruro (2001). UNESCO (ed.). Formulario de Candidatura para la proclamación del Carnaval de Oruro como Obra Maestra del Patrimonio Oral e Intangible de la Humanidad [Candidature Form for the proclamation of the Carnaval de Oruro as Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity] (PDF) (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Fortún, Julia Elena (1961). La danza de los diablos [The dance of the devils]. Autores bolivianos contemporáneos (in Spanish). Vol. 5. La Paz, Bolivia: Ministerio de Educación y Bellas Artes, Oficialía Mayor de Cultura Nacional. OCLC 3346627.

- Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe (1980) [1615]. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacucho (ed.). El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno [The First New Chronicle and Good Government] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Caracas, Venezuela. ISBN 84-660-0056-9. OCLC 8184767.

- Harris, Max (2003). «The Sins of the Carnival Virgin (Bolivia)». Carnival and other Christian festivals: folk theology and folk performance. Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long series in Latin American and Latino art and culture. Austin, United States: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70191-5. OCLC 52208546.

- Salles-Reese, Verónica (1997). From Viracocha to the Virgin of Copacabana: representation of the sacred at Lake Titicaca (1 ed.). Austin, United States: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77713-2. OCLC 34722267.

- Santa Cruz, Nicomedes (2004). LibrosEnRed (ed.). Obras Completas II. Investigación (1958-1991) [Complete Works II. Investigation (1958-1991)]. Obras completas, Nicomedes Santa Cruz (in Spanish). Vol. 2. ISBN 1-59754-014-5.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diablada.

- Cultures Ministry of Bolivia Archived 2009-10-11 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Folklore’s Group Association — Oruro (in Spanish)

- National Culture Institute — Peru (in Spanish)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A Diablada dance squad passing through the streets during the Oruro Carnival in Bolivia. |

|

| Genre | Folk dance |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Pre-Columbian Andean civilizations |

| Year | 1500s |

| Origin | Altiplano region, South America |

The Diablada, also known as the Danza de los Diablos (English: Dance of the Devils), is an Andean folk dance performed in the Altiplano region of South America, characterized by performers wearing masks and costumes representing the devil and other characters from pre-Columbian theology and mythology.[1][2] combined with Spanish and Christian elements added during the colonial era. Many scholars have concluded that the dance is descended from the Llama llama dance in honor of the Uru god Tiw,[3] and the Aymaran ritual to the demon Anchanchu, both originating in pre-Columbian Bolivia,[4][5] though there are competing theories on the dance’s origins.

While the dance had been performed in the Andean region as early as the 1500s, its name originated in 1789 in Orouro, Bolivia, where performers dressed like the devil in parades called Diabladas. The first organized Diablada group with defined music and choreography appeared in Bolivia in 1904.[2][6] There is also some evidence of the dance originating among miners in Potosi, Bolivia,[7] while regional dances in Peru and Chile may have also influenced the modern version.

History[edit]

Pre-Columbian origins[edit]

Bolivian historians claim that the Diablada originated in that country, and that Oruro should be named as its place of origin under the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity policy promoted by UNESCO; Bolivia has also claimed that performances of the dance in other countries are cultural appropriation.[8][9] Bolivian historians currently maintain that the Diablada dates back 2000 years to the rituals of the Uru civilization dedicated to the mythological figure Tiw, who protected caves, lakes, and rivers as places of shelter. The dance is believed to have originated as the Llama llama in the ancient settlement of Oruro, which was one of the major centers of the Uru civilization.[10][11] The dance includes references to animals that appear in Uru mythology such as ants, lizards, toads, and snakes.[12][13][14] Bolivian anthropologist Milton Eyzaguirre adds that the ancient cultures of the Bolivian Andes practiced a death cult called cupay, with that term eventually evolving into supay or the devil figure in the modern Diablada.[15]

Due to syncretism caused by Spanish influence in later centuries, Tiw was eventually associated with the devil; Spanish authorities also outlawed several of the ancient traditions but incorporated others into Christian theology.[16] Local and regional Diablada festivals arose during the Spanish colonial period and were eventually consolidated as the Carnaval de Oruro in the modern city of that name.[10]

…The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro….

— Proclamation of «Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity» to the «Carnival of Oruro», UNESCO 2001

Chilean and Peruvian organizations suggest that since the dance has roots in Andean civilizations that existed before the formation of the current national borders, it should belong equally to the three nations.[17] Some Chilean historians concede that the Diablada originated in Bolivia and was adopted for Chile’s Fiesta de La Tirana in 1952, though it is also influenced by a similar 16th Century Chilean tradition called Diablos sueltos.[18]

Some Peruvian historians also concede that the dance originated in Bolivia but was influenced by earlier traditions practiced across the Altiplano region, including some specific to Peru.[19][20] The Peruvian version, Diablada puneña, originated in the late 1500s among the Lupaka people in the Puno region, who in turn were influenced by the Jesuits; with that dance merging with the Bolivian version in the early 1900s.[21][22] Scholars who defend the Diablada’s origins in Peru cite Aymaran traditions surrounding the deity Anchanchu that had been documented by 16th Century historian Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.[4][23] There is also a version of the Diablada in Ecuador called the Diablada pillareña.[24]

Spanish influence[edit]

Some historians have theorized that the modern Diablada exhibits influences from Spanish dance traditions. In her book La danza de los diablos, Julia Elena Fortún proposed a connection with the Catalan entremés called Ball de diables as performed in the Catalonian communities of Penedès and Tarragona. That dance depicts a struggle between Lucifer and the archangel Saint Michael and is first known to have been performed in 1150.[25][26] Catalan scholar Jordi Rius i Mercade has also found similarities between the Ball de diables and several Andean dances including the similarly-themed Baile de Diablos de Cobán in Guatemala and Danza de los diablicos de Túcume in Peru.[25]

Those theories contradict the more common theory that the modern Diablada is most influenced by the Spanish practice of autos sacramentales during which the colonizers introduced Christianity to the natives of the Andes, due to differing conceptions of the devil and his temptations.[27] The autos sacramentales process has been cited as an influence on the emergence of the Diablada puneña in Peru, shortly after the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, as believed by Garcilaso de la Vega.[28] Peruvian scholar Nicomedes Santa Cruz and Bolivian anthropologist Freddy Arancibia Andrade have suggested a similar process, with the dance originating among miners who rebelled against the Spanish at Potosi in 1538 while combining the ancient ritual of Tinku with Christian references.[7][29] Andrade has also proposed a similar process among striking miners in 1904 as the origin of the modern version of the Diablada.[7]

Post-independence period[edit]

Though the traditions of the Diablada were merged with Christianity during the colonial period, the meanings of the original traditions were revived and reassessed during the Latin American wars of independence. The Altiplano region, particularly around Lake Titicaca, became a center of appreciation for pre-Columbian dance and music.[30] During the Bolivian War of Independence, the main religious festival honoring the Virgin of the Candlemas was replaced by Carnival, which allowed for greater acknowledgement of pre-Christian traditions including the Diablada. The present annual Diablada festival was established in Oruro by 1891.[31]

The first institutionalized Diablada dance squad was the Gran Tradicional y Auténtica Diablada Oruro, founded in Bolivia in 1904 by Pedro Pablo Corrales.[32] That squad established a counterpart called the Los Vaporinos in Peru in 1918.[33] A squad from Bolivia was invited to travel to the Fiesta de la Tirana in Chile in 1956, and that country’s first established squad was called Primera Diablada Servidores Virgen del Carmen, centered in Iquique.[34] In 2001, the Carnaval de Oruro was declared one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, along with the Diablada and 19 other dances performed at the festival.[35] In 2004, the Bolivian government awarded high national honors to the Gran Tradicional y Auténtica Diablada Oruro for its 100th anniversary.[36]

Choreography[edit]

Diablada dancers in Puno, Peru.

In its original form, the dance was performed with music by a band of Sikuris, who played the siku. In modern times the dance is accompanied by an orchestra. Dancers often perform on streets and public squares, but the ritual can also be performed at indoor theaters and arenas. The ritual begins with a krewe featuring Lucifer and Satan with several China Supay, or devil women. They are followed by the personified seven deadly sins of pride, greed, lust, anger, gluttony, envy, and sloth. Afterwards, a troop of devils come out. They are all led by Saint Michael, with a blouse, short skirt, sword, and shield. During the dance, angels and demons move continuously. This confrontation between the two sides is eclipsed when Saint Michael appears and defeats the Devil. The choreography has three versions, each consisting of seven moves.[37]

Music[edit]

The music associated with the dance has two parts: the first is known as the March and the second one is known as the Devil’s Mecapaqueña. Some squads play only one melody or start the Mecapaqueña in the fourth movement «by four».[37] Since the second half of the 20th century, dialogue is omitted so the focus is only on the dance.[38]

Regional variations[edit]

Diablada Puneña (Peru)[edit]

The Diablada Puneña originated in modern Peru with the in the Lupaka people in 1576, when they combined tenets of Christianity from the autos sacramentales with ancient Aymara traditions.[4][23] Some additional influences from the cult of the Virgin Mary were added in the following century.[22] The Peruvian version of the Diablada was quite different from the Ururo-based Bolivian version until the two merged at the Fiesta de la Candelaria in 1965. However, the Peruvian versions continue to feature homegrown figures like Superman, American Indians, ancient Mexicans, and characters from popular films.[39]

The costumes used in the Peruvian Diablata also include influences from Tibet as well as elements from pre-Columbian Peruvian cultures such as Sechin, Chavin, Nazca, and Mochica.[4] Homegrown masks were produced and sold in Peru starting in 1956.[40] Music for the dance was originally performed on the siku,[41] but that was later replaced by percussionists known as Sicu-Morenos.[39]

Fiesta de La Tirana (Chile)[edit]

In Chile, the Diablada is performed during the Fiesta de La Tirana in the northern region of that country. The festival attracts more than 100,000 visitors annually to the small village of La Tirana.[42] The festival is descended from the celebrations for the Virgin of Carmen that began in 1540.[42]

See also[edit]

- Carnaval de Oruro

- Fiesta de la Candelaria

- Fiesta de La Tirana

References[edit]

- ^ Kartomi, Margaret J.; Blum, Stephen (1994). Music-cultures in Contact: Convergences and Collisions. p. 63. ISBN 9782884491372.

- ^ a b Real Academia Española (2001). «Diccionario de la Lengua Española – Vigésima segunda edición» [Spanish Language Dictionary — 22nd edition] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

Danza típica de la región de Oruro, en Bolivia, llamada así por la careta y el traje de diablo que usan los bailarines (Typical dance from the region of Oruro, in Bolivia, called that way by the mask and devil suit worn by the dancers).

- ^ «Bolivia (Plurinational State of) — Information related to Intangible Cultural Heritage». UNESCO. 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

The town of Oruro, situated at an altitude of 3,700 metres in the mountains of western Bolivia and once a pre-Columbian ceremonial site, was an important mining area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Resettled by the Spanish in 1606, it continued to be a sacred site for the Uru people, who would often travel long distances to perform their rituals, especially for the principal Ito festival. The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro.

- ^ a b c d Rubio Zapata, Miguel (Fall 2007). «Diablos Danzantes en Puno, Perú» [Dancing devils in Puno, Peru]. ReVista, Harvard Review of Latin America (in Spanish). VII (1): 66–67. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Morales Serruto, José (3 August 2009). «La diablada, manzana de la discordia en el altiplano [The »Diablada», the bone of contention in the Altiplano]» (Interview) (in Spanish). Puno, Peru: Correo. Retrieved 27 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://www.carnavaldeoruroacfo.com/documentos/FORMULARIO%20DE%20CANDIDATURA.pdf Archived 2009-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Compilation of historians, anthropologists, researchers and folklorists about the Carnival of Oruro and La Diablada

- ^ a b c Arancibia Andrade, Freddy (20 August 2009). «Investigador afirma que la diablada surgió en Potosí [Investigator affirms that the »Diablada» emerged in Potosí]» (Interview) (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ «Perú dice que la diablada no es exclusiva de Bolivia» [Peru says that the Diablada is not exclusive of Bolivia]. La Prensa (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: Editores Asociados S.A. 14 August 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Echevers Tórrez 2009

- ^ a b A.C.F, O. 2001, pp.10-17.

- ^ Guaman Poma de Ayala 1615, p.235.

- ^ Claure Covarrubias, Javier (January 2009). «El Tío de la mina» [The Uncle of the mine] (in Spanish). Stockholm, Sweden: Arena y Cal, revista literaria y cultural divulgativa. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Ríos, Edwin (2009). «Mitología andina de los urus» [Andean mythology of the Urus]. Mi Carnaval (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Ríos, Edwin (2009). «La Diablada originada en Oruro – Bolivia» [The Diablada originated in Oruro – Bolivia]. Mi Carnaval (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ «La diablada orureña se remonta a la época de los Urus precoloniales» [The Diablada of Oruro goes back to the times of the Pre-Columbian Urus]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. 9 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ A.C.F, O. 2001, p.3.

- ^ Moffett, Matt; Kozak, Robert (21 August 2009). «In This Spat Between Bolivia and Peru, The Details Are in the Devils». The Wall Street Journal. p. A1. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Memoria Chilena diabladas» (in Spanish).

- ^ Américo Valencia Chacon. «Candelaria una propuesta frente a una gran responsabilidad» (in Spanish).

- ^ Luis Valverde Caldas. «La diablada como danza» (in Spanish).

- ^ Cuentas Ormachea 1986, pp. 35–36, 45.

- ^ a b Morales Serruto, José (3 August 2009). «La diablada, manzana de la discordia en el altiplano [The »Diablada», the bone of contention in the Altiplano]» (Interview) (in Spanish). Puno, Peru: Correo. Retrieved 27 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b McFarren, Peter; Choque, Sixto; Gisbert, Teresa (2009) [1993]. McFarren, Peter (ed.). Máscaras de los Andes bolivianos [Masks of the Bolivian Andes] (in Spanish). Indiana, United States: Editorial Quipus. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ «Municipio realiza actualización del avalúo para el bienio 2016-2017». Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ a b Rius I Mercade 2005

- ^ Fortún 1961, p. 23.

- ^ Fortún 1961, p. 24.

- ^ De la Vega, Garcilaso; Serna, Mercedes (2000) [1617]. «XXVIII». Comentarios Reales [Royal Commentaries]. Clásicos Castalia (in Spanish). Vol. 252 (2000 ed.). Madrid, Spain: Editorial Castalia. pp. 226–227. ISBN 84-7039-855-5. OCLC 46420337.

- ^ Santa Cruz, 2004, p. 285.

- ^ Salles-Reese 1997, pp. 166-167.

- ^ Harris 2003, pp. 205-211.

- ^ «La diablada orureña se remonta a la época de los Urus precoloniales» [The Diablada of Oruro goes back to the times of the Pre-Columbian Urus]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. 9 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Cuentas Ormachea 1986, pp. 35–36, 45.

- ^ «El folclor de Chile y sus tres grandes raíces» [The Chile’s folklore and its three great roots] (in Spanish). Memorias Chilenas. 2004. Archived from the original on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ «Bolivia (Plurinational State of) — Information related to Intangible Cultural Heritage». UNESCO. 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

The town of Oruro, situated at an altitude of 3,700 metres in the mountains of western Bolivia and once a pre-Columbian ceremonial site, was an important mining area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Resettled by the Spanish in 1606, it continued to be a sacred site for the Uru people, who would often travel long distances to perform their rituals, especially for the principal Ito festival. The Spanish banned these ceremonies in the seventeenth century, but they continued under the guise of Christian liturgy: the Andean gods were concealed behind Christian icons and the Andean divinities became the Saints. The Ito festival was transformed into a Christian ritual, celebrated on Candlemas (2 February). The traditional llama llama or diablada in worship of the Uru god Tiw became the main dance at the Carnival of Oruro.

- ^ «La Diablada De Oruro, máscara danza pagana» [The Diablada of Oruro, mask pagan dance] (in Spanish). 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ a b Fortún, Julia Elena (1961). «Actual coreografía del baile de los diablos» [Current choreography of the devils dance]. La danza de los diablos [The dance of the devils] (DOC). Autores bolivianos contemporáneos (in Spanish). Vol. 5. La Paz, Bolivia: Ministerio de Educación y Bellas Artes, Oficialía Mayor de Cultura Nacional. OCLC 3346627.

- ^ Gisbert 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Cuentas Ormachea, Enrique (23 August 2009). «Diablada: coreografía, vestimenta y música» [Diablada: choreography, clothing and music]. Los Andes (in Spanish). Puno, Peru. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Jiménez Borja, Arturo (1996). Fundación del Banco Continental para el Fomento de la Educación y la Cultura (ed.). Máscaras peruanas [Peruvian masks] (in Spanish). Lima, Peru. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore (Bolivia) (2003). MUSEF (ed.). Serie anales de la reunión anual de etnología [Records of the annual reunion of ethnology series] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. La Paz, Bolivia: MUSEF. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ a b «Danzas ceremoniales del área cultural del Norte» [Ceremonial dances of the northern cultural area] (in Spanish). Chile: Hamaycan. Archived from the original on June 9, 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

Articles:

- Eckels, Charlene (17 October 2013). «Dance of the Devils» [Dance of the Devils]. Yareah. New York, New York. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Cajías, Fernando (23 August 2009). «La diablada orureña ya era noticia en el siglo XIX» [The Diablada of Oruro was already news in the 19th century]. La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Cuentas Ormachea, Enrique (March 1986). «La Diablada: Una expresión de coreografía mestiza del Altiplano del Collao» [The Diablada: A mixed race choreographic expression of the Altiplano in the Collao]. Boletín de Lima (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Editorial Los Pinos. year 8 (44). ISSN 0253-0015. Archived from the original (PNG) on June 16, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- Echevers Tórrez, Diego (3 October 2009). «Sobre diablos y diabladas, A propósito de apreciaciones sesgadas» [About devils and Diabladas, speaking about biased interpretations]. La Patria (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Gisbert, Teresa (December 2002). «El control de lo imaginario: teatralización de la fiesta» [The control of the imaginary: theatralization of the party] (PDF). Módulo: Estudios de caso – Session 14, Lecture 3 (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- Rius i Mercade, Jordi (18 January 2008). «Concomitàncies entre els balls de diables catalans i les diabladas d’Amèrica del Sud» [Concomitances between the Ball de diables and the Diabladas of South America] (in Catalan). Tarragona, Spain: Junta del Ball de Diables www.balldediables.org. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Thomas M Landy, «Dancing for the Virgin at La Tirana», Catholics & Cultures updated February 17, 2017

Books

- Asociación de Conjuntos del Folklore de Oruro (2001). UNESCO (ed.). Formulario de Candidatura para la proclamación del Carnaval de Oruro como Obra Maestra del Patrimonio Oral e Intangible de la Humanidad [Candidature Form for the proclamation of the Carnaval de Oruro as Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity] (PDF) (in Spanish). Oruro, Bolivia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Fortún, Julia Elena (1961). La danza de los diablos [The dance of the devils]. Autores bolivianos contemporáneos (in Spanish). Vol. 5. La Paz, Bolivia: Ministerio de Educación y Bellas Artes, Oficialía Mayor de Cultura Nacional. OCLC 3346627.

- Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe (1980) [1615]. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacucho (ed.). El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno [The First New Chronicle and Good Government] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Caracas, Venezuela. ISBN 84-660-0056-9. OCLC 8184767.

- Harris, Max (2003). «The Sins of the Carnival Virgin (Bolivia)». Carnival and other Christian festivals: folk theology and folk performance. Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long series in Latin American and Latino art and culture. Austin, United States: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70191-5. OCLC 52208546.

- Salles-Reese, Verónica (1997). From Viracocha to the Virgin of Copacabana: representation of the sacred at Lake Titicaca (1 ed.). Austin, United States: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77713-2. OCLC 34722267.

- Santa Cruz, Nicomedes (2004). LibrosEnRed (ed.). Obras Completas II. Investigación (1958-1991) [Complete Works II. Investigation (1958-1991)]. Obras completas, Nicomedes Santa Cruz (in Spanish). Vol. 2. ISBN 1-59754-014-5.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diablada.

- Cultures Ministry of Bolivia Archived 2009-10-11 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Folklore’s Group Association — Oruro (in Spanish)

- National Culture Institute — Peru (in Spanish)

Боливийские праздники: Диаблада

Диаблада — традиционный боливийский карнавал, находящийся под защитой ЮНЕСКО, как «устно-визуальное достояние человечества». Карнавал также известен традиционным Южно-Американский танцем, который создан в Андеан Альтипадо, характеризующийся маской и костюмом дьявола, надеваемыми танцорами.

Пишет Мария Плотникова: Собственно, этот карнавал и был главной причиной моей поездки в Боливию. В карнавальных традициях Диаблады тесно переплелись языческие и христианские ритуалы. Давным-давно мифическому индейскому полубогу Вари (Wari) не понравилось поведение подвластного ему народа уру-уру, и он решил послать на землю гигантских муравьев, змею, крокодила, лягушку и кондора. Твари потихоньку наползали на поселение провинившихся индейцев (ныне – город Оруро, столица карнавала), и вдруг в дело вмешалась Дева Мария. Властью, данной ей свыше, она остановила чудовищ, превратив их в песчаные холмы (и поныне их можно увидеть в окрестностях города). А так как Оруро – шахтерский город, то и Спасительница стала называться Мария де Сокавон (Мария Шахтерская). На месте ее чудесного явления жители города построили церковь, которая стала конечным пунктом карнавального шествия. А сам карнавал символизирует благодарность Деве, спасшей уру-уру от неминуемой гибели. В 2011 году официальное Открытие карнавала было 5 марта, но карнавальные гуляния в Оруро продолжались в течение нескольких недель.

Конечно, возникновение карнавала можно объяснить и более приземленными россказнями, ведь в шахтах Оруро в свое время и золотишко водилось, а негры, которых добрые испанцы штабелями свозили на Альтиплано, не могли вынести тяжелейших условий высокогорья, тысячами умирая во время исполнения своих прямых обязанностей. Таким образом, коренное население, т.е. индейцы, оказались единственной пригодной для эксплуатации рабочей силой. И вот, испанцы, которым мало было только физического подчинения индейцев, решили вплести в их головы и свою религию. Дело в том, что упомянутое божество Вари, хоть и было отрицательным персонажем в мифологии уру-уру, все-таки сильно не дотягивало до вселенского зла дьявола. И индейцы наивно полагали, что этот чертов испанский дьявол не так уж и плох, а вообще-то именно от него зависит удачливость шахтера в деле добывания минералов. И по сей день дьявол, которого индейцы сердечно называют El Tio (от исп. «дядя»), является покровителем всех боливийских шахтеров, и его изваяния можно встретить в закоулках многих шахт. Испанцы бились-бились, и внушили-таки боливийцам, что Мария круче и в конечном счете надо молиться ей, а не дьяволу. Но так как дьявол дает минерал, то его образ сгодится для карнавала, где, как известно из европейский средневековых традиций, все наоборот – плохое становится хорошим, слуга может на равных общаться с хозяином посредством маски и т.п. (см. работы Бахтина). Так что теперь именно в Боливии своими глазами можно увидеть отголоски средневековых традиций карнавала, зачахшего в Европе в каких-то там лохматых веках. А боливийцы действительно искренне верят во все эти чудеса и легенды, и карнавальный танец для них является очищением от грехов. Словом, в ЮНЕСКО не дураки сидят, чтоб провозглашать «устно-визуальным достоянием человечества» какой-нибудь там карнавалишко вроде бразильского. Это мы, темные, только и слышим Рио-Рио, сиськи-жопы, а на Земле вон что творится.

1.

2. За неделю до открытия Диаблады все участники карнавала идут в церковь Марии де Сокавон и приносят торжественную клятву танцевать в ближайшие три года.

3. В пятницу (накануне карнавала) происходит очень важный ритуал переодевания Девы Марии в новые одежды, которые она будет носить весь последующий год. Также проводится ритуал окуривания карнавального костюма и маски дьявола. Специально избранные «посредники» чинно-благородно обнажают Марию до нижнего белья.

4. После смены одежды произносятся различные молитвы и заклинания.

5. Посредники совершают сложные индейские ритуалы сжигания .

6. Далее они окуривают карнавальный костюм.

7. После официальной части подтягивается первый ящик пива. Перед первым глотком все обязаны пролить немного напитка на пол, отблагодарив тем самым Пачамаму (мать-Землю); Мария также получает свою порцию пива.

8. Затем подтягивается второй, третий и т.д. ящик пива и начинается пьянка-гулянка. Помнится, в три часа ночи меня буквально донесли до дома добрейшие посредники. Наверное, прониклись моим именем :).

9. Карнавал начинается в 8 утра. Маска архангела лежит на асфальте перед началом выступления первой танцевальной группы.

10. Некоторые участники после тяжелой ноченьки опаздывают к началу карнавала. Люцифер впопыхах поправляет маску дьяволице.

11. Раньше карнавальные костюмы украшали стеклом и металлом, а теперь — китайским пластиком. Зато и весят они на порядок меньше.

12. Зрители с раннего утра занимают места на трибунах.

13. Архангел Михаил танцует во главе группы дьяволов.

14. Дьяволицы появились в танцевальных группах лишь во второй половине ХХ века (но сначала в женских костюмах все равно танцевали мужчины).

15. Боливийское высокогорное лето — это дождь, температура 10-15 градусов и пронизывающий ветер.

16. Маски дьяволов глубоко индивидуальны по своему дизайну.

17. Каждую танцевальную группу сопровождает нанятый оркестр.

18. В таких забавных костюмах выступают карнавальные группы под названием «моренада» (от исп. moreno — «темный»). Их танцы и одеяния символизируют тяжелую долю, выпавшую на плечи африканских рабов, свозимых колонизаторами со всех концов Африки для работ в высокогорных шахтах Боливии .

19. Танцор в костюме Смерти работает на публику.

20. Некоторые маски настолько тяжелы и неудобны, что их приходится поддерживать во время танца.

21. Во время прохода женских танцевальных групп зрители во всю глотку орут «Beso! Beso!» («поцелуй, поцелуй!»), и девушки иногда посылают воздушный поцелуй, но далеко не всем.

22. Прохожие подвергаются жестокой пенной атаке.

23. Зрители располагаются на всех доступных местах.

24.

25. Мальчик стоит в специальном коридоре, проход через который смывает все грехи.

26. Маска дьявола со змеей — один из главных символов Диаблады.

27.

28.

29. Карнавальное шествие длится два дня — в субботу и воскресенье. Суббота (открытие Диаблады) — наиболее ответственный день, а вот в воскресенье можно пройтись и без маски.

30. Медведь — главный карнавальный заводила.

31. В короткие моменты отдыха танцоры предпочитают снимать маски.

32. Участник карнавала на выступлении, символизирующем борьбу со смертными грехами.

33. Медведь (Хукумари) — один из героев индейской мифологии. Танцоры в костюмах медведей развлекают зрителей, шутят и паясничают во время карнавального шествия.

34. Несмотря на дождь, зрители не расходятся до глубокой ночи.

35.

36. Многие танцоры подставляют под подбородок специальную губку, чтобы смягчить удары маски.

37.

38.

39. Особое внимание при оформлении маски уделяется глазному яблоку диавола.

40. Некоторые танцоры имеют настолько твердый лоб, что никакая ткань не спасает от ритмичных ударов маски.

41. Устал, бедненький.

42. После 5-километрового маршрута по основным улицам Оруро вся нечисть направляется в церковь Марии де Сокавон.

43. В церкви падре отпускает грехи участникам карнавала.

44. После молитвы можно наконец и расслабиться, выпить, поесть.

45. Подвыпившие жены инкских императоров.

46. В красных глубоких блюдечках пьют чичу — слабоалкогольный напиток из кукурузы. Чичу обычно пьют ведрами, группируясь по 5-6 человек и передавая наполненный черпак по кругу из рук в руки. Выпил — зачерпнул — передал.

47.

48. Дева Мария на связи (через посредника, конечно же).

49. Музыканты из разных оркестров с удовольствием под пивко общаются друг с другом.

50. После выступления участники карнавала расходятся по домам, чтобы переодеться и с новыми силами продолжить веселиться.

51. Если пиво покупается в бутылке, то употребить его следует по принципу «и немедленно выпил», т.к. продавцы требуют вернуть стеклотару тут же, на месте. Тогда как жестяную банку можно спокойно забрать с собой и не спеша, прогуливаясь, утолить жажду. На сборе жестяных банок во время карнавала люди сколачивают целое состояние.

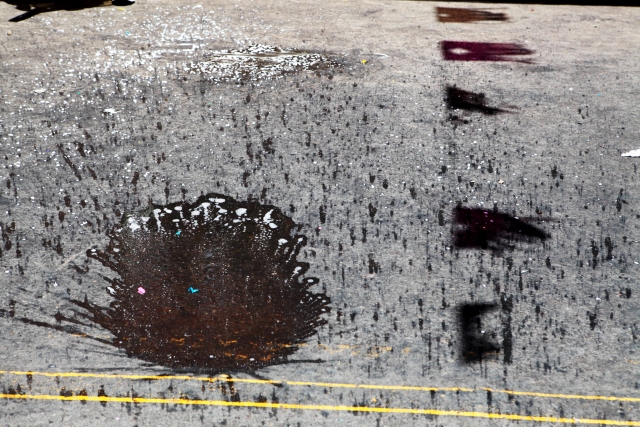

52. Клякса от водной капитошки, предназначавшейся моей спине.

53. Унылое утро после карнавального сумасшествия.

54. Ну и я :).

А вы знали, что у нас есть Telegram и Instagram?

Подписывайтесь, если вы ценитель красивых фото и интересных историй!

Крупнейшее ежегодное празднование в Боливии, которое проводится в течение 10 дней до Пепельной среды, является массовым мероприятием, которое собирает около 400 000 человек.

ЮНЕСКО прозвал карнавал шедевром наследия человечества, крупный праздник в Боливии, проходящий каждый год — событие, собирающее огромное количество человек. В центре событий La Diablada — «Танец дьяволов», необычайное представление, которое показывает демонических танцоров в ошеломляющих костюмах.

Entrada (входная процессия) в длину 4 км, происходит по субботам перед Пепельной средой и на нём задействовано столько людей, что весь парад продлится до 20 часов. Главный персонаж — Сан Мигель. За ним, выплясывая, идут дьяволы и многочисленные медведи, и кондоры.

У самого главного — Люцифера, выдающийся костюм, с накидкой и маской. На его стороне два других дьявола, в том числе Супай, андский бог зла, обитающий на холмах и шахтах. За процессией следуют другие танцевальные коллективы, транспортные средства, украшенные драгоценностями, монетами и серебром, и шахтеры, которые предлагают минерал высочайшего качества Эль Тио, демонического персонажа, который владеет всеми подземными минералами и драгоценными металлами.

Когда архангел и дьяволы прибывают на городской футбольный стадион, они участвуют в серии танцев, которые рассказывают историю окончательного сражения между добром и злом. После того, как становится очевидным, что добро одержало победу над злом (ура!), танцоры уходят на Сантуарио де ла Вирхен дель Сокавон на рассвете в воскресенье, и проводится месса в честь Девы, которая объявляет, что добро победило.

Хотя сегодня это христианский праздник, происхождение La Diablada доколумбовское. Когда испанцы запрещали ритуалы Уру, они превращались в нечто приемлемое для христианского мира, когда боги Анд были размыты в христианских образах.

События продолжаются в течение недели и включают воззвания чаллы, в которых алкоголь разбрызгивается по мирским товарам (и четырем близлежащим скальным образованиям), чтобы призвать благословение. Карнавал заканчивается в понедельник после Пепельной среды Дьялом Агуа — Днем Воды — огромной битвой с водными бомбами, в которой вы, как посетитель, скорее всего, будете главной целью.

Итак, если вы всетаки решили поехать на карнавал Оруро, то вот вам некоторые советы по безопасности:

- Защищайте вещи от воды ли оставляйте свои ценности в отеле. Вы — главная цель для водяных бомб, и любые дорогие гаджеты, в том числе камеры, смартфоны и часы не будут защищены от злых дьяволов!

- Так как страна находится на большой высоте от уровня моря, акклиматизация может стать для вас большой проблемой, как и для многих путешественников в Боливию. Поэтому если вы собираетесь получить заряд энергии на этом фестивале, вы должны прибыть в Оруро на несколько дней раньше, чтобы акклиматизироваться.

- В связи с тем, что на карнавал съезжает в город около 400 000 человек, необходимо заранее побеспокоится о гостиннице, и забронировать номер в отеле.

- Карнавал — раздолье для мелких воров, поэтому держите все свои сбережения под пристальным наблюдением.

Танец дьявола: яркие фото и видео, подробное описание и отзывы о событии Танец дьявола в 2023 году.

- Туры на майские в Перу

- Горящие туры в Перу

Пуно считается фольклорной столицей Перу, особенно бережно хранящей традиции предков.

Один из таких переходящих из поколения в поколение обычаев — «Ла-Диаблада» или «Танец дьявола». Этот южно-американский танец в ярких костюмах популярен в Боливии, Чили и Перу, и без него не обходится ни одно карнавальное шествие и национальный праздник.

Происхождение традиции точно не установлено. Во-первых, каждая из южно-американских стран имеет собственную версию, во-вторых, различия существуют даже внутри регионов.

Согласно одному из преданий, уличный карнавал — наследие, доставшееся жителям Перу от эпохи конкистадоров, пришедших завоевывать эту землю совсем не в ангельском виде.

В Пуно, в частности, его исполняют во время важнейшего религиозного праздника, посвященного Деве де ля Канделария, в феврале. Отдельно на Диабладу можно посмотреть в начале ноября. Суть действа заключается в том, что мужчины предстают в виде танцующих демонов. Возглавляет всю эту процессию сам дьявол.

Практическая информация

Время и место проведения: все традиционные праздники, карнавалы и фестивали.

Вопросы о Перу

Арекипа и окрестности

- Где остановиться: в отелях, гостевых домах или шикарных виллах города Арекипа.

- Что посмотреть: колониальный «город королей» Лиму, современный облик которого сложился благодаря причудливому переплетению двух традиций — индейской и испанской. Древнюю столицу инков — Куско, уникальный «белый город» Арекипу и затерянный в джунглях Мачу-Пикчу. Кроме того, стоит оправиться в путешествие к крупнейшему высокогорному озеру Титикака, по водной глади которого дрейфуют острова индейцев Урос. Наконец, можно пару дней выделить для путешествия в «сердце Боливии» Ла-Пас — уникальный город, расположенный в древнем кратере вулкана, который является самой «высокой» столицей в мире.

- Вас также могут заинтересовать Куба, Доминикана, Мексика, США, Япония.

- Самые популярные города и регионы страны: Арекипа, Куско, Лима, Мачу-Пикчу, Титикака.

Скоро на «Тонкостях»: Почему в аэропортах России все так дорого, а в заграничных аэропортах — нет?

Конфиденциальность данных гарантируется, от подписки можно отказаться в любой момент

Карнавал Оруро, Боливия

Оруро — небольшой шахтерский городок с серыми однотипными домами, который раз в году превращается в одно из самых ярких мест на планете. Как такое возможно? Здесь в преддверии Великого поста проходит трехдневный карнавал, в котором принимают участие более 30 000 танцоров и 10 000 музыкантов! В программе — «танцы дьявола», театральные постановки-мистерии и, конечно же, море смеха и безудержного веселья!

Традиция карнавала Оруро сохранилась с доколумбовых времен

Традиция проведения карнавала берет свое начало от древнейших доколумбовых верований индейцев уру. Тогда действо было посвящено двум божествам — богине-матери Пачамами, символизирующей светлое начало, и божеству гор Тио Супай, олицетворявшему злых духов. Извечная борьба света и тени, добра и зла — вот та связующая нить, которая объединяет древний ритуал с сегодняшним действом.

Яркий и красочный карнавал Оруро

Оригинальные наряды для фестиваля

Карнавал Оруро — самое яркое событие в культурной жизни Боливии

Испанские конкистадоры запретили карнавал в 17 веке, и праздник организовывали подпольно, конечно же, далеко не с таким размахом, как сейчас. Однако в 1756 году в одной из шахт на серебряных рудниках была обнаружена фреска с изображением Девы Марии. Случай воспринимают до сих пор как чудо, и карнавал отныне посвящают Деве Марии Шахт. Вот такой своеобразный синкретизм традиций.

Дьявольские маски на карнавале Оруро

Коренные индейцы до сих пор проживают в Оруро

Торжественный марш под брызги шампанского

Главное событие во время празднования — торжественный парад, который длится безостановочно 20 часов. Десятки тысяч танцоров и музыкантов, более 150 оркестров — вся эта масса людей под оглушительную барабанную дробь проходит живым потоком по центральной улице Оруро. Танцоры олицетворяют злые и добрые силы, схватку, в которой всегда побеждает жизнь, радость и веселье. Для так называемой «диаблады» («танцев дьявола») они одеваются в розовые трико, красно-белые ботинки, украшенные драконами и змеями, а на лицах у них красуются устрашающие маски с рогами и свирепым взглядом. Дизайн костюмов постоянно меняется, на этом специализируются несколько местных мастерских. Стоимость нарядов может достигать нескольких сот долларов, что по меркам боливийцев — целое состояние.

Танцевальные коллективы на карнавале Оруро

Танцевальные коллективы на карнавале Оруро

В карнавальном марше принимают участие и дети…

… и взрослые

Оркестры на карнавале Оруро

Музыкальное сопровождение марша

Масштабы карнавала впечатляют!

Чтобы перенестись в атмосферу праздника, достаточно посмотреть зажигательное видео с прошлогоднего карнавала Оруро.

О том, как проходят национальные праздники в других странах мира, можно узнать из красочного фотообзора «Карнавал шагает по планете«.

Понравилась статья? Тогда поддержи нас, жми:

Мария Плотникова,

26 февраля 2020, 12:37 — REGNUM Февраль — самый праздный месяц Латинской Америки. Ни одна уважающая себя латиноамериканская страна палец о палец не ударит в течение недели до карнавальной недели и недели после праздника. В Боливии водители автобусов могут выйти на забастовку, если власти запрещают им работать в нетрезвом виде. В Бразилии на карнавал приходится всего два официальных выходных, но по факту всеобщая вакханалия приносит стране не меньший экономический урон, чем коронавирус — Китаю. Но кто же считает эти потери?

Вероятно, 100% населения Земли что-то да слышали про знаменитый бразильский карнавал, а некоторые мечтают на него попасть, но буквально в соседней стране, индейской Боливии, проходит не менее красочное и самобытное действо, популярное только среди жителей континента.

В 2011 году я жила в Аргентине, и когда местные прожужжали мне все уши рассказами о Диабладе (таково официальное название карнавала в Боливии), я не задумывалась ни минуты перед выбором: вместо томного тропического Рио я поехала в высокогорный, отбирающий последние физические силы шахтерский городок Оруро. И я не прогадала.

Условно боливийский карнавал можно разделить на несколько частей в хронологическом порядке:

Оркестр отдыхает во время остановки карнавальной процессии

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Этот карнавал — традиционный праздник шахтеров, работающих в одной из самых высокогорных шахт мира. Покровитель шахтеров — Дьявол — соединил в себе как положительное (индейская мифология), так и отрицательное (католичество) начало. Тем не менее горняки связывают свою удачливость именно с милостью дьявола и благодарят его в безумных карнавальных танцах. Шахтерский карнавал в Потоси празднуется на две недели раньше официального католического карнавала.

Участницы карнавала направляются к месту сбора танцевальных групп на фоне шахты Богатой горы

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Первый день гуляний проходит у подножия Богатой горы

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

На второй день карнавала праздник перемещается на центральные улицы Потоси

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Карнавал в Потоси длится два дня. Различные кооперативы шахтеров представляют на празднике свои танцевальные группы. Карнавал начинается около 10 утра, но столь ранний час не мешает основной массе шахтеров совершить первые возлияния дьяволу.

Во время танцев участники карнавала впадают в абсолютный транс

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Дети шахтеров также участвуют в карнавале, танцуя в своих мини-группах

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Музыкальные оркестры – главная статья расходов танцевальных групп. Танцоры нанимают музыкантов за свои деньги

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Этот праздник не имеет ничего общего с христианской культурой

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

«Аната» в переводе с аймарского языка означает «игра». Это карнавал индейских цивилизаций доиспанского периода, который отмечается в сезон дождей в высокогорье Анд и символизирует благодарность крестьян Пачамаме (Земле).

Вид на Оруро во время карнавала

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

В Анате участвует более ста коллективов

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Индейцы восхваляют Пачамаму и просят у нее обильных дождей в году грядущем. Альтиплано (Андское нагорье) отличается очень засушливым климатом, поэтому урожай напрямую зависит от количества выпавших осадков.

Карнавальные коллективы не нанимают оркестры, а сами играют на народных музыкальных инструментах

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Индейцы объединяются в довольно большие группы, каждая из которых представляет свой регион Альтиплано. Праздничное шествие проходит за два дня до открытия главного боливийского карнавала — Диаблады.

Участники, танцуя, выпивая, веселясь под народные музыкальные инструменты, проходят по центральным улицам города Оруро

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Национальные костюмы сотканы из чистейшей шерсти ламы

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Танцор в костюме Люцифера. Маска дьявола со змеей — один из главных символов Диаблады

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Диаблада — традиционный боливийский карнавал, находящийся под защитой ЮНЕСКО как «устно-визуальное достояние человечества». В карнавальных традициях Диаблады тесно переплелись языческие и христианские ритуалы. Давным-давно мифическому индейскому полубогу Вари (Wari) не понравилось поведение подвластного ему народа уру-уру, и он решил послать на землю гигантских муравьев, змею, крокодила, лягушку и кондора. Твари потихоньку наползали на поселение провинившихся индейцев (ныне — город Оруро, столица карнавала), и вдруг в дело вмешалась Дева Мария. Властью, данной ей свыше, она остановила чудовищ, превратив их в песчаные холмы (в наше время их можно увидеть в окрестностях города). Так как Оруро — шахтерский город, Спасительница стала называться Мария де Сокавон (Мария Шахтерская). На месте ее чудесного явления жители города построили церковь, которая стала конечным пунктом карнавального шествия. А сам карнавал символизирует благодарность Деве, спасшей уру-уру от неминуемой гибели.

Накануне карнавала происходит очень важный ритуал переодевания Девы Марии в новые одежды, которые она будет носить весь последующий год. Также проводится ритуал окуривания карнавального костюма и маски дьявола

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Посещение церкви Марии де Сокавон является обязательной частью карнавала. Именно там падре отпускает грехи всем участникам карнавала

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Зрители с раннего утра занимают места на трибунах

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Трибуны строят из любых подручных материалов, а зрители ничего не имеют против стоячих мест

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Трибун на всех не хватает, и зрители располагаются на всех доступных местах

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Самые неприхотливые зрители

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Мастерская по изготовлению карнавальных костюмов в Оруро

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Элемент декора карнавального костюма

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Однако на карнавале в Потоси мы уже выяснили, что боливийские шахтеры считают дьявола своим покровителем, и его изваяния можно встретить в закоулках многих шахт. В Диабладе эта амбивалентность прекрасно обыгрывается согласно лучшим традициям средневекового европейского карнавала. Символ абсолютного зла в христианской культуре для боливийцев становится чуть ли не родственником (индейцы сердечно называют его El Tio — от исп. «дядя»), его образ воспевается в карнавальных костюмах и танцах.

Герб одной из танцевальных групп

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Женские танцевальные группы смогли выступать в карнавале лишь со второй половины ХХ века (изначально в женских костюмах танцевали мужчины)

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Участник карнавала на выступлении, символизирующем борьбу со смертными грехами

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Раньше карнавальные костюмы украшали стеклом и металлом, а теперь — китайским пластиком. Зато и весят они на порядок меньше

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Многие танцоры подставляют под подбородок специальную губку, чтобы смягчить удары маски

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Карнавал начинается в 8 утра. Маска архангела лежит на асфальте перед началом выступления первой танцевальной группы

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Удивительно, что в наше время именно в Боливии своими глазами можно увидеть отголоски средневекового карнавала, давно зачахшего в Европе. Боливийцы же действительно искренне верят во все эти чудеса и легенды, и карнавальный танец для них является очищением от грехов.

Мальчик стоит в специальном коридоре, проход через который смывает все грехи

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Во время прохода женских танцевальных групп зрители во всю глотку орут «Beso! Beso!» («поцелуй, поцелуй!»), и девушки иногда посылают воздушный поцелуй, но далеко не всем

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

После выступления участники карнавала расходятся по домам, чтобы переодеться и с новыми силами продолжить веселиться

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Карнавальное шествие длится два дня — в субботу и воскресенье. Суббота (открытие Диаблады) — наиболее ответственный день, а вот к концу воскресенья «доживают» немногие

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Главная карнавальная улица

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Во время гуляний участники праздника постоянно посыпают головы друг друга конфетти. Это символизирует благодарность Пачамаме

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

«Чьайя» (Ch´alla) — ежегодный индейский обряд, совершаемый в следующий после Диаблады (главного боливийского карнавала) вторник. Ch´alla — название этого обычая по-аймарски.

Женщин в традиционных боливийских одеяниях называют «чолитами» (cholitas)

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Музыкальный оркестр неотступно следует за праздничной процессией

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

На оркестр ложится основная нагрузка по развлечению публики

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Шествие замыкает знаменосец, неся в руках флаг с названием рабочего кооператива

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Коренные жители Боливии благодарят Пачамаму (землю) за данный им в этом году урожай и просят благополучия в следующем году. Просьбы и благодарности выражаются в форме всеобщей пьянки, танцах и веселье. Родственники одной семьи или рабочего кооператива объединяются в группы, нанимают оркестр и с раннего утра начинают обход домов и магазинов, пригласивших их заранее.

За время гуляний удается обойти около 15–20 дворов

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Пиво льется рекой

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Дети принимают активное участие в карнавале

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

К середине дня силы покидают некоторых музыкантов

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Хозяева каждого «двора» проставляются несколькими ящиками пива, которое нужно употребить тут же, а участники этого мини-карнавала освящают землю, машины и остальное имущество тем же пивом. Съемки проходили в городке Уюни, но подобный ритуал совершается во всех населенных пунктах высокогорной части Боливии.

Мария Плотникова © ИА REGNUM

Читайте развитие сюжета:

В ожидании жизни. Год назад в России был введён режим самоизоляции