Еврейский народ один из самых древних, его история насчитывает более трех тысячелетий. Как нацию, евреев отличают преданность традициям, прагматичность и высокий интеллект (согласно многочисленным исследованиям ученых, средний показатель IQ евреев – 108-115, тогда как в Европе и Азии он составляет около 80). Рассеянные по всему миру в результате вынужденной многовековой ассимиляции, иудеи, несмотря на религиозное и культурное влияние стран, где они проживали, смогли сохранить свою национальную сущность.

Религиозные традиции

Практически все национальные обычаи и традиции у евреев так или иначе связаны с религией, которая регламентирует все сферы их жизни. Даже календарей у этого народа два: в повседневной жизни используется общепринятый юлианский, а религиозное летоисчисление ведется от даты сотворения мира (то есть в настоящий момент идет уже 5778 год). В календаре евреев отмечены праздничные и траурные даты, которые связаны со знаменательными событиями в жизни народа, описанными в священных книгах.

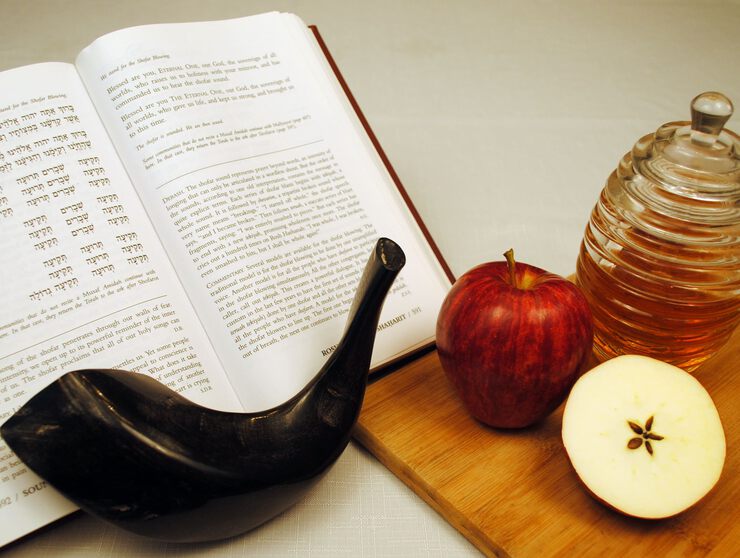

Самым значительным из праздников считается Новый год (Рош-А-Шона). Его отмечают в новолуние месяца тишрей (по юлианскому календарю это сентябрь-октябрь месяц). Середина осени считается временем, подходящим для осмысления уходящего года, оценки совершенных дел и раскаяния в неблаговидных поступках. На стол подают символические блюда:

- рыбьи головы как пожелание руководствоваться в своих действиях умом, а не эмоциями;

- овощи и фрукты, чтобы следующий год был щедрым;

- яблоки с медом, чтобы год был сладким;

- гранат, зерна которого символизируют многочисленные добрые события в жизни.

Кроме Рош-А-Шона, к традиционным еврейским праздникам относятся:

- Пейсах ― семидневный праздник в честь Исхода израильтян из Египта.

- Иом-Кипур ― день поста, покаяния и молитв об отпущении грехов.

- Суккот ― семидневный праздник, напоминание о сорокалетних скитаниях народа в пустыне. Для Суккота сооружается специальный шалаш, и все трапезы совершаются вне дома.

- Пурим ― праздник в память о спасении иудеев в V столетии до Р.Х от истребления.

- Рош Ходеш ― отмечается в первый день лунного месяца.

- Ташлих ― религиозный очистительный обряд, который проводится в первый день Рош а-Шана. Еврейские семьи приходят на берега водоемов и совершают молитву о прощении грехов. Затем выворачивают карманы, отряхивают полы одежды, символически сбрасывая с себя прошлые грехи, и бросают в воду крошки хлеба для рыб.

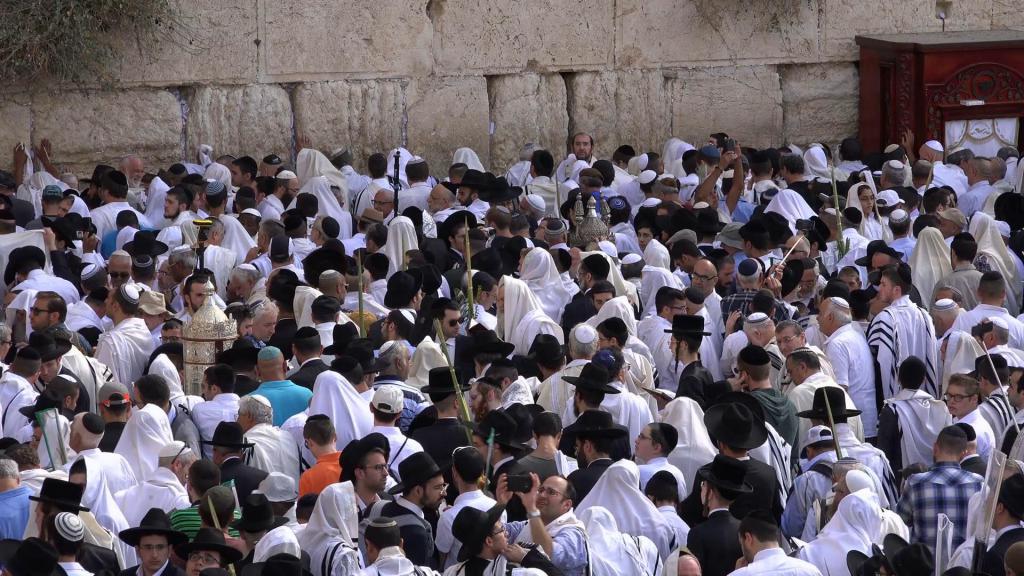

Еврейские праздники обычно начинаются вечером, когда, согласно Торе, зарождается новый день. Галаха (еврейский закон) во время праздника запрещает выполнять любую работу, исключение составляет приготовление пищи. Праздничный день должен проводиться исключительно в отдыхе и молитвах, которые рекомендуется читать в общине, насчитывающей не меньше 10 взрослых мужчин. Считается, что молитва ― это коллективное служение Всевышнему.

Отличительной особенностью еврейских религиозных праздников является их массовость, Перед Всевышним все равны, поэтому в праздничном действе принимают участие и взрослые, и дети. Проведение праздничной трапезы начинается с обязательных ритуалов благословения на вино и хлеб, омовения рук, и только после этого иудеи садятся за стол.

Семейные традиции

Еврейские семьи известны своей прочностью и взаимной заботой. Семейная жизнь строго регламентируется Торой и библейскими канонами. Семьи создаются рано, юноши часто женятся в возрасте 20 лет, девушкам разрешено вступать в брак с 15 лет. Брак с человеком другой национальности не признается законным, даже если он скреплен официальным гражданским актом.

Свадьба

Свадьба («кидушин») согласно национальным традициям евреев, проводится осенью. Для новобрачных сооружается отдельный навес (хула), символизирующий их будущий общий дом. Жених и невеста становятся под балдахин, жених одевает своей суженой кольцо и произносит: «Этим кольцом согласно вере и закону Израиля ты посвящаешься мне». После этого начинается свадебный пир, который длится 7 дней. Застолье сопровождается игрой еврейского оркестра ― скрипки, цимбал, лютни и бубен.

По обычаю, после свадьбы родители на два года предлагают новобрачным кров и стол. Для молодых это и материальная поддержка, и нечто вроде «семейной интернатуры»: они учатся у родителей взаимному уважению и заботе друг о друге.

Семейная жизнь

Важную часть религиозного кодекса евреев составляют семейные традиции. Семья является основой еврейской общины и считается нерушимой, за каждым из ее членов признаются определенные права и обязанности.

Моральное поведение супругов должно быть безупречным. Так, Тора запрещает мужчине даже прикасаться к чужой жене, сестре, дочери или матери. Если замужняя женщина опорочила себя слишком вольным поведением, муж может потребовать официального развода. И повторно выйти замуж разведенная женщина имеет право за любого мужчину, кроме того, с кем совершила супружескую измену.

Тора требует от супругов сохранения душевной чистоты и цельности чувств. Чтобы сексуальные отношения супругов много лет не теряли новизны, и между ними надолго сохранялось состояние «медового месяца», мужу и жене запрещено спать в одной постели: в еврейской спальне должно стоять две кровати.

Рождение детей

Значимым событием в еврейской семье является появление ребенка. Национальность детей определяется не по отцу, как у других народов, а по матери. То есть если мать еврейка, ребенок ― еврей, независимо от того, какой национальности его отец. Если же отец ребенка еврей, а мать ― не еврейка, их ребенок евреем не считается. Ребенок, рожденный вне брака, незамужней женщиной, не считается незаконнорожденным, и в правах не ущемляется. Еще одна отличительная особенность еврейской семьи ― отцы заботятся о детях так же самоотверженно, как и матери.

С рождением ребенка у иудеев связан особый обряд, означающий принятие мальчика в религиозную общину ― обрезание (циркумизация, брит). Это хирургическая мини-операция по удалению крайней плоти, которая проводится мальчикам на восьмой день после рождения, хотя такой обряд может совершаться над мужчинами любого возраста. Обрезание выполняет мохел (моэль) ― человек, для которого совершение обрезания является единственной работой. Такой обычай есть и у некоторых других народов, но только евреи придают ему особое значение, считая обрезание выполнением одной из Господних заповедей.

Проводы в последний путь

Похороны у евреев раньше были довольно сложной и долгой процедурой, в настоящее время проводы в последний путь значительно упрощены. Усопшего хоронят в простом светлом одеянии, считается, что дорогие одежды нарушают принцип всеобщего равенства перед Господом. Над покойником дома и в церкви читаются молитвы, после чего тело предают земле. Кремацию Тора запрещает, но сегодня традиции евреев, проживающих в России и других европейских странах, допускают кремирование, если на то была прижизненная воля покойного. Цветы на могилу приносить не принято, вместо них на надгробие кладут камешки.

Траур по покойнику включает три периода. Первый (шива) продолжается неделю. В это время скорбящие не должны заниматься никакой работой. Второй (шлошим) длится 30 дней, в этот период сохраняются только основные, внешние элементы траура. Третий период, который соблюдается только в случае смерти родителей или ребенка, длится год.

Необычные еврейские обычаи

У евреев есть интересные и необычные традиции и обычаи, которые у других народов не встречаются.

Шаббат

В переводе с иврита – «шаббат» означает «отдых, воздержание от работы». Считается, что Бог сотворил мир за 6 дней, начав с воскресенья, а на седьмой день, в субботу, отдыхал. Поэтому и людям в субботу запрещен любой физический или умственный труд. В некоторых современных еврейских многоэтажках даже есть специальные лифты, которые автоматически останавливаются на каждом этаже, чтобы человек при пользовании такой техникой не совершал никаких действий. Нарушить Шаббат разрешается только ради спасения человеческой жизни.

Кашрут

Это свод правил, который касается пищевых ограничений, и содержит перечень продуктов питания, разрешенных и запрещенных к употреблению.

- Кошерным (разрешенным для употребления) считается мясо только тех животных, которые имеют раздвоенные копыта и относятся к жвачным. Причем должны иметь место оба признака (у свиньи копыта раздвоенные, но она к жвачным животным не относится, поэтому свинину евреям есть запрещено).

- Из птиц можно есть только выращенных в домашних условиях.

- Разрешены виды рыбы, имеющие чешую и плавники.

- Вино разрешено употреблять только изготовленное верующим евреем-виноделом.

- Нельзя смешивать молоко и мясо ― ни в процессе приготовления блюд, ни в трапезе. Перерыв между попаданием мясной и молочной пищи в желудок должен составлять не меньше 6 часов.

Цдака

Одной из основных заповедей иудаизма является оказание помощи нуждающимся («Цдака»). По традиции, у евреев принято в праздники подавать милостыню ― деньги или продукты. При этом делать это нужно, закрыв лицо маской: считается, что анонимность благодеяния убережет подающего от гордыни и подчеркнет, что подаяние, как и любая помощь ― не услуга, а восстановление справедливости.

Камни вместо цветов

На еврейских кладбищах не увидишь цветов, принесенных на похоронах или при посещении могил. Вместо цветов на надгробных камнях лежат камешки. В иудаизме считается, что камень символизирует вечность, и, помещая его на могильной плите усопшего, ты оставляешь рядом с ним частицу своей души.

Традиционные еврейские блюда

Еврейская кухня ― одна из строго регламентированных религиозными обычаями. Из-за необходимости придерживаться обусловленных требованиями Торы традиций даже краткий список продуктов, запрещенных евреям, довольно широк. Тем не менее, в еврейском меню преобладают блюда, которые отличаются прекрасным вкусом и высокой биологической ценностью, в их состав входят легко усваиваемые и полезные для организма вещества.

ТОП-10 самых популярных еврейских блюд:

- Фаршированная рыба. Это национальное еврейское блюдо занимает почетное место на столе в любой праздник, а на Рош-А-Шона его готовят обязательно.

- Форшмак (в переводе с иврита – «предвкушение»). Паштет, приготовленный из селедки, отварного картофеля, сваренных вкрутую яиц и лука.

- Пастрома. Говядина со специями и приправами, запеченная в духовке большим куском. Подается в холодном виде.

- Хала. Праздничный хлеб из сдобного дрожжевого теста.

- Маца. Тонкая пресная лепешка, которую едят на Пасху вместо хлеба.

- Паштида. Особый вид заливного пирога с начинкой из мяса, колбасы, рыбы или овощей.

- Чолнт (хамин). Древнее еврейское блюдо, мясное рагу из бобов или фасоли. Хамин готовят в пятницу, чтобы есть в субботу, когда по требованиям Шаббата готовить пищу нельзя.

- Фалафель. Закуска в виде жареных во фритюре шариков из перемолотого нута или фасоли.

- Кугель. Запеканка из тертого картофеля, риса или лапши с мясом или шкварками.

- Цимес. Десертное блюдо, приготовленное из жареной моркови, чернослива, кураги, изюма, меда и корицы.

Знаменательные даты еврейского календаря имеют два названия на иврите: «моадим» и «хагим». Оба слова в их современном значении переводятся на русский язык как «праздники». В эти дни устраивают церемониальные трапезы, запрещен траур, существуют ограничения на выполнение различных работ.

Содержание

-

- Главные еврейские праздники

- Три разновидности праздников

- Когда начинаются праздники?

- Работа в праздничные дни

- Дополнительный день

- Даты праздников евреев

Еврейские праздники наполнены радостью и духовным смыслом. Они призваны выделить это время из суеты будничных дней и посвятить его служению Всевышнему.

Главные еврейские праздники

К основным еврейским праздникам относятся:

- Шаббат – 7-й день недели и один из почитаемых праздников. Это символ союза между еврейским народом и Богом. Отмечается в субботу, как день, когда Всевышний пребывал в покое после того, как 6 дней занимался Сотворением Мира.

- Рош Ходеш – 1-й день месяца, длится один или два дня. Если месяц состоит из 29 дней, то Новомесячье празднуют один день, если же 30 дней, то два. Евреи читают отдельные псалмы из Аллель и дополнительную молитву Мусаф.

- Песах – один из основных иудейских праздников. Установлен в память об Исходе еврейского народа из египетского рабства. За пределами Израиля празднование длится 8 дней. В Израиле его отмечают в течение недели. Во время Песах не разрешается есть хлеб и другие мучные продукты, кроме Мацы.

- Лаг ба-Омер – празднуется в мае. Связан со смертью рабби Шимона бар Йохая (Рашби) – великого учителя и кабалиста. В этот же день прекратилась эпидемия, в результате которой скончалось свыше 24 тысяч учеников рабби Акивы.

- Шавуот – день дарования Торы. Название можно перевести как «недели». В Шавуот принято учиться всю ночь.

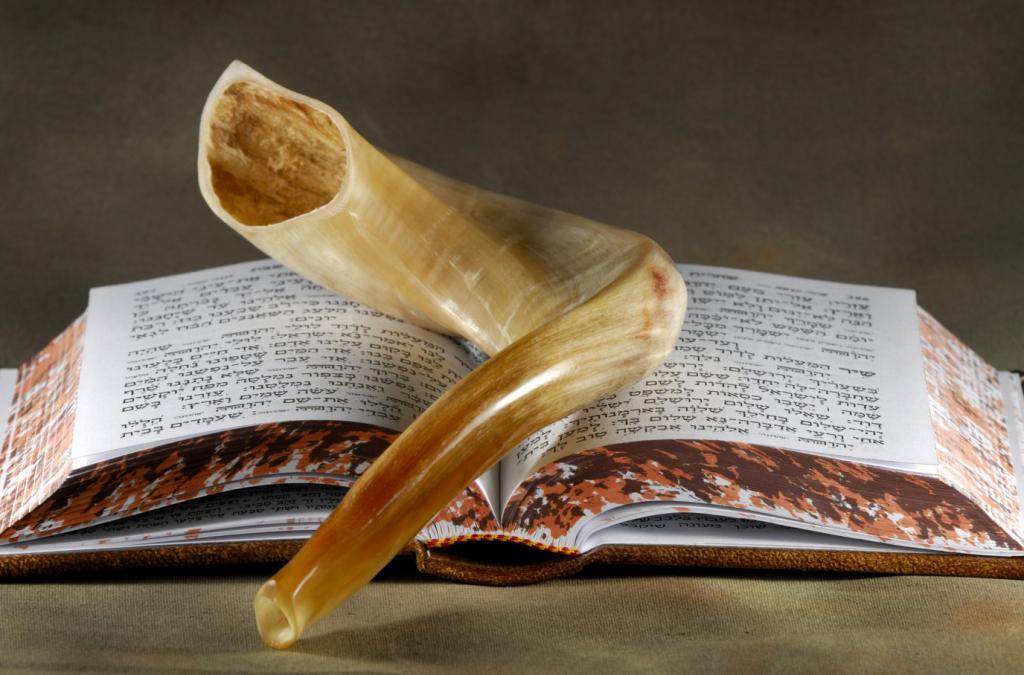

- Рош а-Шана – еврейский Новый год. Проходят продолжительные молитвы, праздничные застолья, во время которых едят яблоко с медом и другие симаним (знаки). В Рош а-Шана заповедано трубить в Шофар – музыкальный инструмент, выдолбленный из рога животного. Всевышний творит суд над людьми на весь последующий год.

- Йом-Киппур – так называют день Искупления. Этот еврейский праздник отмечают в сентябре или октябре. Йом-Киппур является завершающим после 10 дней очищения, молитв, раскаяния и отпущения грехов. Выносится окончательный приговор на будущий год. Все евреи постятся и проводят время в синагогах практически весь день.

- Суккот – один из самых радостных праздников иудаизма. Основная традиция – жить в сукке, покрытом ветками шалаше. Сидеть в Сукке заповедано в память об Облаках Славы, которые защищали евреев от палящего солнца пустыни во время Исхода. За пределами Израиля празднование продолжается девять дней, а в Израиле восемь.

- Симхат Тора и Шмини Ацерет – последние два дня праздника Суккот, а в Израиле –последний 8-й день. В эти дни действует единственная заповедь – радоваться служению Творцу. В Симхат Тора заканчивают чтение Торы в синагоге, и начинают новый годовой цикл с главы Берешит «В начале».

- Ханука – ежегодный праздник, отмечаемый в ноябре или декабре, в память о победе Маккавеев над греческими войсками. Тогда же свершилось чудесное событие: храмовый светильник не гас целых восемь дней, хотя масла хватало всего лишь на одни сутки. В память о чуде мудрецы постановили зажигать восьмисвечник в течении всех дней.

- Ту би-Шват – «Новый год деревьев» и зимний праздник, отмечаемый в феврале или январе. Если плоды завязались после окончания этого праздника, их относят уже урожаю наступившего года. В этот праздничный день принято сажать деревья (это характерно для современного Израиля) и есть плоды, которыми славится земля Израиля. Многие устраивают праздничную трапезу, основные блюда которой –фрукты.

- Пурим – праздник в память о том, как во время Персидского владычества удалось избежать тотального уничтожения по замыслу главного советника царя – Амана-амалекитянина. Сейчас, отмечая это событие, евреи радуются, дарят подарки и пьют вино больше, чем обычно.

Три разновидности праздников

Каждый из религиозных праздников иудаизма имеет свои традиции, предписанные заповеди или обычаи. Возникли они в разное время и диктовались Торой, великими учителями древности или более поздними обычаями. Есть три основных типа еврейских торжеств и памятных дат:

| Рош Ходеш, Йом-Киппур, Рош а-Шана, Шаббат, а также паломнические праздники: Суккот, Шавуот и Песах | Произошли из самой Торой |

| Ханука и Пурим | Установлены древними учителями |

| Лаг ба-Омер, Ту би-Шват и Ту би-Ав | Пост-раввинистические праздники, отличительная черта которых – отсутствие обязательных заповедей |

Как видно, каждый из трех основных типов соответствуют историческому периоду, когда события стали памятными датами еврейского календаря.

Когда начинаются праздники?

Все еврейские праздники начинаются вечером, с заходом солнца, а не после полуночи, как принято в других религиях и светской жизни. В истории Сотворения Мира, описанной в книге Берешит, сказано: «И был вечер, и было утро, день первый». Отсюда вывод, что день начинается с вечера, то есть с заката. Заканчиваются с появлением трех звезд, то есть в то время, когда стемнеет.

Важно. Чтобы узнать точное время начала и окончания праздника в конкретной местности, необходимо воспользоваться специальным еврейским календарем, актуальным для вашего города.

Работа в праздничные дни

Выделяется три разновидности праздников по строгости ограничений:

- Йом-Киппур и Шаббат – строго запрещены все созидательные виды работ;

- Йом тов – так называют любой праздничный день, в него при определённых условиях разрешено приготовление пищи;

- Холь а-Моэд – полупраздничные дни в течение праздничной недели Песах или Суккот, в них разрешено большинство работ, которые необходимы для проведения праздника.

В список запрещенных работ входят следующие виды деятельности:

- зажигание и тушение огня;

- забивание скота;

- охота;

- шитье;

- стрижка овечьей шерсти;

- выпечка и варка;

- молотьба;

- жатва;

- посадка растений

- и другие.

Важно. Законы субботы и праздников имеют множество нюансов и описаны в специальных книгах. На русском языке ознакомиться с основными законами Шаббата можно в книге рава Моше Понтелята «Царица суббота».

Йом товом считаются следующие дни:

- два дня Рош а-Шана;

- первый (а в диаспоре и второй) день Сукот;

- Шмини Ацерет и Симхат Тора;

- первый (а в диаспоре и второй) и последний (а в диаспоре два последних) день Песаха;

- Шавуот (в диаспоре два дня).

Дополнительный день

Вне Израиля евреи отмечают праздники на день больше, чему есть объяснение. Дополнительный день (Йом тов шени) появился так. По лунному календарю каждый месяц начинается с новолуния. Раньше новые месяцы определялись на основе живого свидетельства о появлении молодой луны на небосводе. Когда приезжал гонец, Сангедрин – верховный орган юридической, религиозной и политической власти, объявлял о начале нового месяца и отправлял посланников, чтобы сообщить людям, когда начинается этот месяц.

Евреи в отдаленных общинах не всегда могли быть уведомлены о новолунии (о первом дне месяца), поэтому они не знали точно, какой день праздновать. Им было известно, что в старом месяце будет 29 или 30 дней, поэтому они отмечали праздники в оба возможных дня.

Эта практика стала обычаем даже после того, как был принят точный астрономический календарь. Дополнительный день не отмечается израильтянами, независимо от того, где они находятся во время праздника, потому что это не обычай их предков. Но он отмечается всеми остальными, даже если они в это время посещают Израиль.

Даты праздников евреев

Ниже приведен список основных праздничных дат на ближайшие пять лет. В таблице даны названия праздников и даты. Первое число обозначает день, второе – месяц, третье – год.

Важно. Все праздники начинаются с заходом солнца за день до указанной даты. Для более точных данных рекомендуется воспользоваться еврейским календарём, актуальным для вашей местности.

| Праздник | 2020-21 гг. | 2021-22 гг. | 2022-23 гг. | 2023-24 гг. | 2024-25 гг. |

| Рош а-Шана | 19.09.20 | 07.09.21 | 26.09.22 | 16.09.23 | 03.10.24 |

| Йом-Киппур | 28.09.20 | 16.09.21 | 05.10.22 | 25.09.23 | 12.10.24 |

| Суккот | 03.10.20 | 21.09.21 | 10.10.22 | 30.09.23 | 17.10.24 |

| Шмини Ацерет | 10.10.20 | 28.09.21 | 17.10.22 | 07.10.23 | 24.10.24 |

| Симхат Тора | 11.10.20 | 29.09.21 | 18.10.22 | 08.10.23 | 25.10.24 |

| Ханука | 11.12.20 | 29.11.21 | 19.12.22 | 08.12.23 | 26.12.24 |

| Ту би-Шват | 28.01.21 | 17.01.22 | 06.02.23 | 25.01.24 | 13.02.25 |

| Пурим | 26.02.21 | 17.03.22 | 07.03.23 | 24.03.24 | 14.03.25 |

| Песах | 28.03.21 | 16.04.22 | 06.04.23 | 23.04.24 | 13.04.25 |

| Лаг ба-Омер | 30.04.21 | 19.05.22 | 09.05.23 | 26.05.24 | 16.05.25 |

| Шавуот | 17.05.21 | 05.06.22 | 26.05.23 | 12.06.24 | 02.06.25 |

| Ту би-Ав | 18.07.21 | 07.08.22 | 27.07.23 | 13.08.24 | 03.08.25 |

Несмотря на все перипетии истории еврейскому народу, столетиями следующему заповедям Торы, удается сохранить свои традиции, обычаи и ритуалы. Во многом это благодаря еврейским праздникам, которые возвращают к корням, и не дают забыть чудесные события многовековой еврейской истории.

История еврейского народа содержит немало достаточно печальных фактов. Из-за своей национальности евреи поддавались постоянным гонениям, были вынуждены проживать вне своей исторической родины. Но многострадальный народ выстоял, объединился и сохранил свою национальную идентичность. Еврейские традиции до сих пор почитаются, передаются из поколения в поколение.

Религиозные традиции

Официальной религией Израиля является иудаизм. Более 80 % населения – это иудеи, 15 % – мусульмане, 5 % – христиане и другие. Религиозные евреи соблюдают законы, написанные в еврейской библии – Торе.

Несмотря на то, что иудаизм – основная религия Израиля, в стране действует свобода вероисповедания.

Религия – это то, что объединяет и определяет еврейский народ. Иудаизм регламентирует все сферы жизни человека, а соблюдение заповедей Торы является прямой обязанностью каждого религиозного еврея.

Все традиции и обычаи еврейского народа связаны с религией:

- На 8-ой день после рождения мальчиков, родившихся в еврейских семьях, обрезают. По достижении 13 лет они публично читают главу Торы. Это обязательные обряды для исповедания иудаизма.

- Иудеи должны соблюдать 613 заповедей, 365 из них носят запретительный характер. Существует запрет на богохульство, идолопоклонение, кровосмешение, употребление в пищу мяса животных, которые в Торе названы нечистыми. В список «грязных» животных входят свиньи, зайцы, устрицы, креветки, крабы и т. д.

- Истинные иудеи носят длинные пряди волос на висках – пейсы. Женщины должны прикрывать голову головным убором, когда выходят на улицу.

- Суббота – день посещения синагоги и молитвы. Евреи освобождаются от повседневной работы. В этот день нельзя пользоваться электричеством, стричь волосы или брить бороду, разводить огонь. В субботний вечер проводят церемонию Авдалы, которая есть исполнение заповеди «Помни день субботний, чтобы освятить его».

- Самым значимым праздником является Рош-А-Шана, или Новый год.

- Середина осени считается временем, когда нужно раскаяться в плохих поступках, оценить совершенные дела за год.

- Все религиозные праздники евреев отличаются массовостью. Участие принимают и взрослые, и дети, так как все равны перед Всевышним. За стол садятся только после ритуалов благословения и омовения рук.

- Кошерные, то есть религиозные, евреи, соблюдают дресс-код. В каждой еврейской общине он свой, но есть общие особенности. Дресс-код вводится для девушек старше 12 лет, наиболее он строгий для замужних женщин. Одежда всегда должна быть чистой и опрятной, не слишком дорогой и роскошной, но и не убогой, обязательно скромной. В Торе сказано: «И ходи скромно с твоим Богом». Одежда должна прикрывать те части тела, которые нельзя демонстрировать: декольте, локти, колени. Снимая или надевая нижнее белье, нужно прикрываться одеялом. Одеваться или раздеваться необходимо, начиная с правой стороны, поскольку она главнее, чем левая. Мужчины носят на голове кипу.

Иудаизм – это одна из старейших религий мира. Считается, что от него произошли христианство и ислам. Родоначальником иудаизма считают первого еврея Авраама, который проповедовал веру в Единого Бога, Создателя всего сущего.

Учим лексику:

- религиозный דתי [датИ];

- светский (нерелигиозный) חילוני [хилонИ].

Вера и религия в Израиле очень важны, но различные общины исповедуют Тору с разной степенью религиозности. Наиболее строгое соблюдение библейских законов у ортодоксальных иудеев. Их численность – около 25 % от всего еврейского населения Израиля. Среди крупных религиозных направлений следует выделить реформистский иудаизм и религиозный сионизм.

Есть также частично или полностью нерелигиозные группы (около 75 % всего населения), к которым относятся сионисты, евреи левых взглядов и светские евреи, воспринимающие иудаизм в большей степени как культуру и мировоззрение.

Семейные традиции

Обычаи еврейской семьи регламентируются Торой. Супругам-евреям удается сохранить теплые отношения на протяжении всей семейной жизни, несмотря на то, что союзы заключаются, как правило, достаточно рано. Юноши женятся в возрасте 18–20 лет, а девушки вступают в брак начиная с 15 лет.

Еврейская семья является символом верности, чистоты и прочности.

Свадьба

В еврейских традициях брак играет важную роль. После свадьбы муж с женой становятся единым целым, между ним есть только Творец.

Обычаи и традиции еврейской свадьбы:

- Бракосочетания, или «кидушин», традиционно проводятся осенью. Самое неблагоприятное время для женитьбы – период между Песахом и Щавутом. В эти дни запрещены все гуляния, вечеринки и танцы, нельзя веселиться.

- Перед помолвкой нужно получить согласие и благословение родителей. Жених должен вручить отцу невесты символический выкуп.

- Перед свадьбой женщине необходимо искупаться в ритуальном бассейне без косметики и одежды, а мужчине – помолиться в синагоге. Молодые просят прощения за свои грехи.

- Церемония бракосочетания проходит в синагоге или на площадке возле нее. Молодые становятся под хупой – свадебным балдахином, который символизирует будущий общий дом. Жених надевает кольцо невесте и произносит слова клятвы.

- Свадебная церемония заканчивается коллективной трапезой, которая длится семь дней. Празднование достаточно шумное, гости веселятся, танцуют, поют песни.

- После свадьбы молодая пара год живет у родителей, где изучает азы семейной жизни. Они учатся уважению и заботе друг о друге.

До свадьбы супруги не вступают в интимную близость. Брак заключается только между настоящими евреями. Союз с другими национальностями с точки зрения традиций не считается законным, даже если подписаны официальные документы.

Тора запрещает жениться на кровных родственниках, на бывших женах, на вдове сына, отца, дяди и т. д. Запрет также распространяется на кровных родственников умершей жены. Нельзя вступать в брак с женщиной, которая не получила официальный развод.

Семейная жизнь

Семейные ценности в еврейских семьях передаются из поколения в поколение. Мужчина в доме является главным. Он делает всё, чтобы его семья была счастливой, не нуждалась ни в чем. «Мужчина должен есть и пить меньше, чем ему позволяют средства, одеваться так, как ему позволяют средства, уважать жену и детей больше, чем позволяют средства».

Муж никогда не оскорбит чувства и честь жены, не заставит ее делать мужскую работу, а, наоборот, поможет в выполнении повседневных дел.

Брачный союз между женой и мужем должен напоминать взаимоотношения между человеком и Богом. Важно, чтобы союз был безупречным. Замужняя женщина должна вести себя скромно, за фривольное поведение муж может потребовать развод. В свою очередь, женатый мужчина также не может смотреть на чужих женщин, прикасаться к ним.

В браке важно сохранить душевную чистоту и величие чувств. Чтобы у супругов за годы совместной жизни не пропала страсть, им нельзя спать вместе. В еврейской спальне стоят две кровати – одна для мужа, вторая для жены.

Родители задают тон в доме, прививают детям уважение к старшим и заботу ко второй половинке. По традиции все ссоры и выяснения отношений между супругами-евреями проходят за закрытой дверью. Дети не видят и не слышат конфликты родителей.

Рождение детей

Самым значимым событием в жизни еврейской семьи является рождение ребенка. Евреи очень трепетно относятся к детям, поскольку они являются продолжением их рода. Папы могут присутствовать на родах, с удовольствием берут на себя часть обязанностей по уходу за младенцем, могут остаться с малышом хоть на целый день. Они заботятся о детях так же, как и матери.

Национальность у евреев определяется не по мужской, а по женской линии. Если женщина не еврейка, то ребенок не считается евреем, даже если отец еврей. Несмотря на существующие законы, дети, рожденные вне брака, не считаются незаконнорожденными. Они имеют равные права.

Важно! Еврейское религиозное законодательство Галаха считает «легитимным» евреем только ребенка, рожденного от еврейки. Происхождение отца не имеет значения. Негалахические евреи могут перейти в еврейство, пройдя обряд «Гиюр».

Важным обрядом, связанным с рождением ребенка, является брит-мила, или обрезание. Его проводят на 8-ой день в утренние часы или днем. Его выполняет человек, который занимается обрезанием, – моель. Им может быть только благочестивый еврей.

Мальчику дают имя после обрезания, а девочку нарекают им в синагоге в первую субботу после рождения. Отец может назвать сына в честь человека, у которого учился Торе, дать двойное имя, например: Моше-Хаим, Менахем-Мендл. Не запрещено называть детей именами ближайших родственников.

Согласно традиции Израиля отец выкупает сына-первенца у матери. Обряд выкупа называется пидьон абен. Существуют следующие правила его проведения:

- не делают, если ребенок появился в результате кесарева сечения, а также в субботу, праздники и посты;

- проводят на 31-ый день после рождения малыша, если отец не сможет совершить обряд в это время, то он должен его сделать до исполнения сыну 13 лет;

- церемонию проводит коен;

- для ритуала нужно приобрести пять специальных серебряных монет, которые выпускает Государственный банк.

Обряд очень прост, заканчивается благословением отца и коена.

Похоронные церемонии

Похороны по еврейским обычаям ранее считались сложной и долгой процедурой, которая сейчас значительно упрощена. Покойного стараются как можно быстрее придать земле, иногда даже хоронят в день смерти.

Несмотря на традицию предавать тело умершего земле как можно скорее, в субботу похороны не проводят.

Организацией похоронного процесса занимаются дальние родственники. Близкие готовятся морально и физически. Накануне похорон им нельзя мыться и стричься, пользоваться косметикой, употреблять вино или мясо. Нужно отказаться от тяжелой физической работы и чтения молитв.

Тело покойного омывают, облачают в траурную одежду, обязательно светлую и не дорогую, на глаза кладут черепки. Обувь не надевают. Тело мужчины укрывают молитвенным покрывалом.

Покойного кладут в гроб с отверстием в дне. По традиции обязательно закрывают крышку, поскольку тело усопшего нельзя выставлять напоказ и касаться его. В помещении, где находится покойник, не курят, не употребляют пищу и алкоголь.

Евреи считают смерть естественным процессом, трагедией является только внезапная гибель. Для проявления высшей степени скорби близкие родственники на одежде делают надрывы.

Тело всегда предают земле, кремацию запрещает Тора. Цветы на могилу не приносят, вместо них по традиции на надгробие кладут камешки. В иудаизме камень является символом вечности. Помещая его на могильную плиту, человек оставляет частицу своей души.

Поминки не устраивают, но принимают поминальную трапезу, которая состоит из вареных яиц и круглых постных булочек.

Период траура включает три этапа:

- Шива. Длится семь дней. Близкие родственники должны сидеть дома и скорбеть по усопшему. В этот период нельзя принимать гостей, заниматься любой работой.

- Шлошим. Длится с 7-го по 30-ый день смерти. Дух усопшего, который первую неделю обитал в доме, переходит в мир иной. Родственники по-прежнему должны скорбеть и носить разорванную одежду, но могут выходить в общество и выполнять важную работу.

- Год. Этот этап соблюдают только в случае смерти родителей или ребенка. Скорбь длится год. Скорбящие ограничивают себя в развлечениях, но могут вести привычную жизнь.

Траур соблюдают ближайшие родственники: родители, дети, братья и сестры. На годовщину смерти они собираются вместе, чтобы почтить память усопшего.

Традиции

В Израиле много интересных традиций, которые присущи только евреям. Особый интерес представляет Шабат и другие религиозные торжества. В праздничные дни не работают госучреждения и даже прекращается движение общественного транспорта, чтобы люди могли посвятить себя молитве.

Любой праздник начинается вечером предшествующего дня, а завершается с заходом солнца.

Шабат

В Израиле неделя начинается с воскресенья, а суббота является седьмым днем. Выходные в стране начинаются после обеда пятницы.

Праздник евреев Шабат буквально переводится как «суббота», означает «отдыхать», «прекращать». Это вековая еврейская традиция в 7-ой день недели воздерживаться от любой работы, включая умственный труд.

«В седьмой день недели все дела делай только для Бога».

В честь этого праздника надевают праздничную одежду, посещают службу в синагоге.

В Шабат запрещено:

- включать электрические приборы и вообще пользоваться электричеством;

- зажигать и тушить огонь;

- пользоваться любой техникой, даже заводить машину;

- выполнять работу по дому, работать в огороде;

- стричься;

- пользоваться косметикой;

- готовить, подогревать пищу;

- употреблять спиртные напитки;

- вышивать, шить, вязать узлы;

- заниматься спортом;

- играть на музыкальных инструментах;

- что-либо покупать или продавать (в Шабат нельзя думать о материальных ценностях);

- играть свадьбы, устраивать похороны и т. д.

В современных израильских многоэтажках есть даже специальные лифты, которые останавливаются на каждом этаже, чтобы евреи не пользовались техникой и не нарушали Шабат.

В субботу закрыты магазины и рынки, работают только экстренные службы. Подробнее о Шабате.

Кашрут

Одна из самых главных традиций евреев – кошерное питание. Кашрут – это свод правил, касающихся приема пищи, взятый из Торы. Его соблюдает еврейский народ как в повседневной жизни, так и при посещении святых мест.

Основные правила кашрута:

- Евреи должны употреблять только кошерную пищу, то есть еду, приготовленную по иудейским законам.

- Разрешены все виды рыбы, которые имеют чешую и плавники. Ракообразные не пригодны для потребления в пищу, поскольку не кошерные.

- Самые строгие ограничения касаются мяса. «Животное можно есть, если оно жвачное и парнокопытное». Кошерные животные – это коровы, овцы, козы, а также дикие олени, лоси, газели. Нельзя употреблять в пищу кровь, поэтому мясо перед приготовлением нужно замочить в воде, а затем засыпать солью. Во время забоя скота заботятся о том, чтобы этот процесс был максимально безболезненным. Резник проходит специальные курсы и сдает экзамены. После забоя он обязательно проверяет все внутренние органы животного. Если оно было больным, то мясо употреблять в пищу нельзя.

- Птицу можно есть только домашнюю, как и яйца. Если в желтке есть кровь, то ее обязательно удаляют.

- Нельзя совмещать мясное и молочное ни в процессе приготовления, ни в процессе потребления еды. Евреи руководствуются следующим принципом: «Не варить козленка в молоке матери его». Промежуток между попаданием мясной и молочной пищи в желудок должен составлять не менее 6 ч. Рыбу можно есть и с молоком, и с мясом.

- Кошерным является вино, выращенное только на территории Израиля, исключительно верующим евреем-виноделом.

- Насекомых нельзя употреблять в пищу, поэтому зелень, фрукты, овощи и крупы тщательно отбирают.

В Израиле едят из кошерной посуды. Если в тарелке хранилась некошерная еда, то она ужа становится некошерной.

Цдака

Это одна из главных заповедей в иудаизме. Касается она благотворительности. Согласно Торе евреи должны помогать друг другу, оказывать как физическую, так и материальную помощь.

«Не ожесточай сердца твоего и не сжимай руки твоей перед братом твоим нищим».

Цдака отражает фундаментальный принцип иудаизма: «Всё, что у меня есть, я получил от Всевышнего, именно Он – подлинный хозяин моего достояния. Раз Он предписывает мне делиться с братом-евреем, я должен делать это с радостью».

Заповедь о цдаке должен исполнять даже бедный человек, который сам нуждается в материальной помощи. По традиции в праздничные дни нуждающимся подают милостыню – продукты или деньги. Делают это с целью восстановить справедливость, а не показать свое благородство.

Традиционные праздники

Евреи отмечают праздники, которые есть в Торе: Песах, Шавуот, Суккот, Рош-А-Шана и Йом-Кипур. Кроме них, существуют праздничные дни, возникшие в память о значимых для еврейского народа событиях. К ним относятся Ханука, Пурим, Лаг-ба-Омер и посты.

Для евреев праздник – это значимое событие, время, когда можно обратиться ко Всевышнему, высказать ему слова благодарности и попросить прощения за грехи. Израильтяне ходят в синагогу, устраивают праздничные трапезы, совершают специальные обряды.

Песах

Праздник Песах у евреев – это еврейская Пасха, которая имеет мало общего с христианской. Это важное для израильтян событие посвящено освобождению еврейского народа от рабства в Древнем Египте и спасению всех еврейских младенцев.

Праздник отмечают на 14-ый день первого месяца Нисан, который соответствует периоду март – апрель. Празднование длится неделю.

Современные традиции Песаха:

- К празднику готовятся, в доме делают генеральную уборку. Жилье очищают не только от мусора и ненужных вещей, но и от некошерной еды. Обязательно перемывают всю посуду горячей водой.

- Накануне праздника хозяин дома обходит все комнаты и углы со свечой в поисках некошерной еды. Всё обнаруженное обязательно уничтожают.

- Главная традиция Песах – это священный ужин. К запрещенным продуктам на столе относится всё, что приготовлено методом брожения. Вместо традиционного кулича на еврейскую Пасху едят пресный хлебец из пшеничной муки, который называется маца.

- По традиции наполняют пять бокалов вином. Четыре выпивают, а последний оставляют на столе для пророка Элияху.

Песах – это религиозный праздник, поэтому верующие евреи посещают синагогу, где проводятся богослужения. В первый и последний день Пасхи запрещена любая работа. Всю неделю принято праздновать и благословлять Всевышнего. Еще больше интересного о Песахе.

Рош-А-Шана

Одним из главных национальных праздников Израиля является еврейский Новый год. Его отмечают не один, а целых два дня. Новый год в Израиле приходится на новолуние осеннего месяца Тишри. По еврейскому календарю это период сентябрь – октябрь.

Для евреев Рош-А-Шана, как и все праздники, имеет свою историю и значимость. Согласно легенде в первый день нового года Всевышний творит суд над еврейским народом, определяет, что должно случиться с людьми.

Традиции Рош-А-Шана:

- Накануне женщины зажигают свечи, так как являются хранительницами домашнего очага.

- Израильтяне читают молитвы, которые содержат десять текстов о Боге. Обязательно просят о помиловании и прощении грехов.

- В синагогах используют специальный инструмент из бараньего рога, который называется шофар.

- В Рош-А-Шана накрывают праздничный стол, за которым собирается вся семья. Традиционно читают молитву, а после приступают к трапезе. Главным блюдом на столе является фаршированная рыба. Обязательно обмакивают хлеб в мед, чтобы год был сладким. Не ставят на стол кислое, горькое и острое.

- Евреи поздравляют друзей и родственников с Новым годом, даря подарки. Особо ценным пожеланием является фраза: «Желаю быть вписанным в Книгу жизни».

Существует древняя традиция собираться на Рош-А-Шана на берегу водоема, читать молитвы и кормить рыбу крошками из карманов. Такой обряд позволяет очиститься от грехов. Подробнее о празднике.

Йом-Кипур

На десятый день после Рош-А-Шана евреи празднуют Йом-Кипур. К этому празднику начинают готовиться сразу после Нового года. В подготовку входит омовение и ношение белой одежды.

Йом-Кипур – это День искупления. Называется он в честь того, что в эту дату Всевышний простил еврейскому народу грех золотого тельца. В праздник продолжительностью 25 ч. ничего не работает – закрыты все магазины, кафе, государственные учреждения.

Евреи соблюдают строжайший пост, исключают из рациона даже воду. Под запретом плотские утехи, веселья. В этот день нельзя умываться, носить кожаную обувь и смазывать кожу.

Важной традицией для женатых мужчин является зажигание «свечи жизни», которая должна гореть сутки. Подробнее о празднике.

Суккот

После Йом-Кипура отмечают праздник кущей, который еще называют «временем нашей молодости». Главная его задача – принести великую радость. В Торе он упоминается так: «И веселитесь пред Господом семь дней».

По традиции в течение недели нужно жить в сукке – ярко украшенном шалаше. Его строят по всей стране в честь праздника. Важным законом Суккот является соединение четырех растений – ветви финиковой пальмы, пахучей мирты, скромной ивы и цитрона, произнесение над ними благословения. Еще о Суккоте.

Ханука

Этот праздник – один из самых важных в иудаизме. Его отмечают целых восемь дней. Он посвящен освобождению еврейского народа от греческого ига.

По традиции ежедневно зажигают свечи и ставят их в подсвечник – ханукию, который должен стоять на подоконнике. Количество свечей зависит от дня празднования: в первый – одну, во второй – две и т. д.

В Хануку не нужно соблюдать пост, наоборот, накрывают пышный стол. Все веселятся, для детей устраивают развлечения. В период празднования нельзя оплакивать усопших, пока горят свечи, следует отказаться от выполнения домашних дел.

Интересно! По традиции на Хануку пекарни во фритюре выпекают пончики со сладкой начинкой, посыпанные сахарной пудрой. За восемь дней празднования в Израиле съедают около 17 млн пончиков.

Другие любопытные факты о Хануке.

Пурим

Самым веселым праздником в Израиле считают Пурим. Его празднуют в начале весны. Он является символом единения и спасения еврейского народа, установлен в память о спасении евреев от уничтожения во времена Персидской империи, демонстрирует непобедимость израильтян.

Его празднование напоминает карнавал. Люди резвятся и дурачатся, устраивают пир, а также отправляют посылки с продуктами близким, делают подарки бедным. В Пурим запрещены посты и проявления траура. Можно заниматься любой работой, но лучше посвятить свободное время веселью.

«Тот, кто совершает работу в Пурим, должен знать, что она не удостоится благословения». Подробнее о Пуриме.

Четыре Новых года

В Израиле отмечают целых четыре Новых года. Такого больше нет ни в одной стране мира. В каждом сезоне еврейского календаря есть свой Новый год для:

- исчисления года правления царей – весна;

- отделения десятины от скота – лето;

- счета лет от сотворения мира (Рош-А-Шана), который считается главным и больше всего напоминает европейский праздник, – осень;

- деревьев – зима.

Ни один новогодний праздник в Израиле не приходится на первое января. Европейский Новый год израильтяне не отмечают.

Новомесячье (Рош Ходеш)

Это полупраздничный день, посвященный женщинам. Он является началом нового месяца, в осенний сезон совпадает с Рош-А-Шана.

Для многих современных евреев Рош Ходеш является обычным днем, который отличается несколькими дополнительными молитвами. Однако женщинам в этот день лучше не работать, так как он выделен Торой. Принято устраивать вечернюю трапезу, надевать праздничную одежду.

Евреи толерантно относятся к людям других религий и национальностей, поскольку дискриминация запрещена Торой. Они очень тепло встречают иностранцев, которые знают хотя бы несколько слов на иврите. Собственный язык для израильтян – большая ценность.

Планируя поездку в Израиль, обязательно выучите несколько слов на иврите и не забывайте о еврейских традициях. Помочь в освоении языка вам может онлайн-школа «Иврика».

Важнейшей частью любого народа являются их праздники. Именно они связывают нас с нашими предками и делают каждую культуру уникальной и неповторимой. Так у иудеев основная часть памятных дней связана с библейскими историями. Многие традиции соблюдались веками и являются частью жизни у жителей Израиля по сегодняшний день. Рассмотрим важнейшие праздники иудаизма в 2019 году.

Ту-Бишват (Новый год деревьев)

В 2019 году отмечался в ночь с 20 на 21 января.

У евреев 4 праздника, посвященных Новому году и Ту-Бишват один из них. Каждый подобный праздник отмечается, как символ чего-либо. Этот посвящен деревьям, а именно по традиции именно на Ту-Бишват подсчитывали возраст деревьев. Также Тора предписывает иудеям отделять десятину, чтобы помочь священнослужителям. Поэтому это еще и день, когда подсчитывали эту самую десятую часть от всего урожая. Когда же все счета готовы, евреи исполняют так называемый седер — выпивают 4 бокала вина и съедают десять определенных фруктов. Все это делается в определенной последовательности. Вечером же все родные собирается для праздничного семейного ужина.

Пурим

В 2019 году отмечался в ночь с 20 на 21 марта.

Это праздник в честь освобождения иудеев от гнета персидского царства. По легенде, приближенным к царю Аманом по жребию (в Израиле его называют Пурим) было решено истребить всех евреев. Но как оказалось, жена Артаксеркса (собственно самого царя) была израильтянкой, а потому вместе со своим дядей смогла спасти своих земляков, а Аман был наказан за свои интриги.

Накануне праздника все соблюдают пост, а в Пурим он заканчивается и евреи устраивают богатую трапезу. Дети и взрослые надевают карнавальные костюмы и выходят на улицы для гуляний, а также, чтобы полюбоваться тематическими театральными постановками.

Песах

В 2019 году отмечался с 19 апреля по 27 апреля.

Самый главный праздник в Израиле отмечают в честь освобождения от египетского рабства. Чем-то он схож с нашей Пасхой. Хозяйки задолго до праздника тщательно убирают дом, украшают его, стирают одежду, готовят еду, занимаются всеми домашними делами, ведь во время торжества делать этого будет нельзя.

Песах длится 8 дней — в первые два дня любая работа запрещена, а потому на улицах Израиля в это время вы не найдете ни одного открытого учреждения; 5 дней запрет немного слабее, а потому работает только часть организаций и только полдня. И уже на следующий день начинается сам праздник.

В первую и последнюю ночь все семьи собираются за праздничным ужином, а накануне собирают деньги для бедняков и раздают им, чтобы и они могли отпраздновать Песах.

Одной из важнейших традиций — уничтожение всего квасного в доме перед праздничной неделей. Все это либо съедают, либо выбрасывают. Утром, накануне Песаха, все первенцы соблюдают строгий пост. Это делается для того, чтобы почтить память всех первенцев, умерших во время десяти казней египетских.

Рош-Ашана

В 2019 году отмечается с 29 сентября по 1 октября.

Это календарный Новый год у израильтян, именно с этого дня у них начинается отсчет дней. Праздник длится несколько дней, а в первый утром трубят в шофар, тем самым напоминая евреям о том, как важно совершать добрые поступки.

Если у нас со всех сторон слышится “Счастливого Нового года!”, в Израиле всем желают попасть в Книгу Жизни. Вечером всех ждет праздничный ужин, где на столе обязательно должна стоять рыба и круглая хала.

Йом-Кипур

В 2019 году отмечается в ночь с 8 на 9 октября.

Можно сказать, что это продолжение Нового года и отмечают его на десятый день после оного. По поверьям в этот день Бог смотрит на дела в ушедшем году и выносит свой вердикт. Поэтому в этот день ничего делать нельзя, кроме анализа и размышления о своей жизни и своих делах, молитвы и чтения Торы. Так как на Йом-Кипур принято соблюдать пост, накануне, вечером всех ждет праздничный семейный ужин.

Суккот

В 2019 году отмечается с 13 по 20 октября.

Праздник отмечают семь дней и все это время принято проводить в сукке — шалаше. Сегодня не часто полностью следуют этой традиции, большинство просто сооружает на балконе или во дворе частного дома что-то похожее на шатер и иногда там молятся, читают Тору, кушают.

Вечером на праздник все евреи отправляются в синагогу и у каждого в руках 4 растения. С этим букетом нужно обойти здание синагоги и в это время зачитывать стихи из Торы.

Ханука

В 2019 году отмечается с 22 по 30 декабря.

Как вы уже поняли по датам, праздник отмечают восемь дней. И по традиции все это время зажигают специальные свечи. В первый день одну, во второй — две, в третий — три и так далее. Добавлять свечи важно именно слева направо и никак иначе.

Все эти дни иудеи гуляют с размахом, а поститься и вовсе запрещено. У детей обычно начинаются каникулы, а взрослые обязательно угощают их сладостями на протяжении всей Хануки. Также, согласно поверьям, даже самые бедные в эти дни найдут свою радость и могут надеяться на чудо.

Хануку чаще всего называют именно детским праздником, так как многие традиции связаны именно с ними. Детям принято дарить подарки, деньги, при этом часть своего дохода ребята должны пожертвовать на благотворительность.

Эта традиция была введена специально, чтобы научить их не только правильно распоряжаться деньгами, но также добру и состраданию. Часто семьи, где много детей, вечерами играют в детскую игру “Волчок”.

Самые важные дни устанавливаются по еврейскому календарю праздников, структура которого указывается в Торе. Календарь лунно-солнечный и основывается на специальных вычислениях, а начало месяцев всегда совпадает с новолунием. Самые важные праздники свято соблюдаются еврейским народом, как и тысячелетия назад. Каждый из них имеет свои традиции и историю. Культура Израиля богата на обычаи, которые с любовью почитаются гражданами страны. Рассмотрим самые значимые еврейские праздники в марте и в другие месяцы года.

Пурим

Праздник, который отмечается в честь чудесного спасения евреев в Персидском царстве. Это событие произошло боле 2400 лет назад, в то время правил царь Ахашверош. Название еврейского праздника Пурим произошло от слова “пур”, или «жребий». Приходится данный праздник на четырнадцатый день месяца адар, по григорианскому календарю – конец февраля или начало марта. В 2018 году Пурим пришелся на 1 марта. 28 февраля, в канун Пурима — день траура и поста перед праздником. В этот день запрещается пить и есть. Знаменует этот пост то время, когда евреи, проживавшие на территории Персии, неустанно молились и соблюдали пост в течение трех дней. В будущем пост сократили до одного дня, ведь продержаться без воды дольше достаточно сложно. В отличие от остальных четырех общественных постов, пост Эстер не имеет строгих законов, и его соблюдение необязательно для беременных и кормящих женщин, для больных и тех, кто занят тяжелым трудом.

Песах

Еврейская Пасха – главный иудейский праздник в память об Исходе из Египта. По еврейскому календарю приходится он на 15-й день месяца нисана и празднуется целую неделю. По григорианскому календарю в 2018 году евреи праздновали Песах с 30 марта по 7 апреля. Первый день Песаха, как и последний – официальные выходные дни. Промежуточные пять дней называются праздничными буднями. В переводе Песах – «прохождение мимо». Такое название является памятью о том, как ангел смерти проходил мимо домов иудеев, расправляясь только с египетскими первенцами. Каждая еврейская семья должна была заколоть ягненка и обозначить его кровью дверные косяки. Таким образом ангел мог отличить их дома от египетских. Уйти из Египта евреям фараон дал возможность только тогда, когда все египетские первенцы были убиты. Песах включает в себя два праздника, которые связаны с сельским хозяйством. Эти еврейские праздники с жертвоприношениями предполагали, что в день нового приплода скота будет принесен в жертву ягненок в возрасте одного года. Второй праздник – день первого сбора урожая ячменя. В это время избавлялись от хлеба и выпекали из пресного теста новый. Называется он маца. В дальнейшем эти праздники было решено объединить в один. Каждый Песах сопровождается традиционной вечерней трапезой в первую и вторую ночь праздника. В оставшиеся дни рекомендуется не работать, но и не запрещается. Нельзя стирать и убирать. В эти дни следует проводить как можно больше времени с близкими, ходить в гости к родственникам, путешествовать по Израилю. Люди из разных уголков Израиля стараются в эти дни посетить Иерусалим. Предписания Торы говорят о том, что в Песах следует посетить Храм в Иерусалиме, а на следующий день принести в жертву ягненка и сноп ячменя в честь соответствующих двух праздников. В последний день праздника евреи отмечают освобождение.

Йом ха-Ацмаут

Нельзя не упомянуть о таком важном для еврейского народа празднике, как День независимости Израиля. Празднуется он в 2018 году 19 апреля. Израиль – молодое государство, независимость которого была провозглашена 14 мая 1948 года. В 1947 году Генеральной Ассамблеей ООН было принято решение разделить Палестину на два государства. Для евреев это был праздник, для арабов – траур, именно поэтому те начали военные действия еще до создания такого государства, как Израиль, в знак протеста. Но не успел Давид Бен-Гурион зачитать Декларацию независимости, как спустя несколько часов армии других стран вступили на территорию Израиля. Евреям снова пришлось взять в руки оружие и защищать землю своих предков. Война длилась год и три месяца. Более шести тысяч человек отдали жизнь за существование Государства Израиль.

Шавуот

Через 50 дней после Песаха евреи получили Тору на горе Синай – этот день получил название Шавуот (праздник дарования Торы). Евреи дали обещание следовать Торе во что бы то ни стало, во все времена и в любом месте. Со дня получения Великой Книги и по настоящее время жизнь еврейского народа основывается на вере в Бога и преданность Его заветам. Евреи выполнили данное у горы Синай обещание и, несмотря на то что многие были разбросаны по всему миру, они остались единой нацией.

Рош ха-Шана

Или так называемый еврейский Новый год. Летоисчисление в Израиле ведется практически с появления первых людей, и в то время как мы встретили 2018 год, 9-11 сентября в Израиле наступил 5779. Этот праздник отмечают все, по всей стране люди обмениваются подарками и поздравлениями, отправляются в гости к друзьям и родственникам, устраивают семейные ужины и вечеринки.

Йом Киппур

Самый главный праздник в иудаизме – день покаяния и молитвы. В 2018 году приходится на 18-19 сентября. Йом Киппур – день поста, отпущения грехов и окончание Десяти дней покаяния. Перед Судным Днем следует вспомнить все, что произошло в прошлом году, проанализировать свои поступки и произошедшие события, вспомнить о своих грехах не только перед Богом, но и перед другими людьми. И как бы устрашающе ни звучало, Йом Киппур – день радости, восстановления сил и настроя на хорошие дела. Человеку свойственно ошибаться, но истинное раскаяние дает Божье прощение. Именно поэтому не муки совести и страх перед небесным судом сопровождают этот день, а душевный подъем и хорошее настроение. Этот день дарит надежду на то, что новый год будет счастливым и удачным.

Суккот

Этот праздник имеет множество названий: праздник шалашей, конец странствий по пустыне, праздник мира, день сбора урожая. На самом деле, Суккот – паломнический праздник, в который еврейский народ собирался в Иерусалиме. Празднуется с 23 по 30 сентября. Отличительная особенность этих дней в том, что евреи оставляют свои дома и отправляются жить в шалаши, которые предварительно устанавливают на улицах. Именно поэтому день имеет название «праздник шалашей». Суть Суккота – почтить историческое прошлое еврейского народа, выразить связь с Родиной. А шалаши – символ сорокалетних странствий евреев по пустыне.

Ханука

День Освящения Храма празднуется в 2018 г. со 2 по 10 декабря. История праздника начинается с того, что по приказу сирийского царя Антиоха Епифана была прекращена служба в иерусалимском храме. И только в 165 году до нашей эры, когда евреи одержали победу над сирийцами, богослужение возобновилось. Существует легенда, что в храме была обнаружена емкость со священным елеем для поджигания семисвечника. Традиция поджигать свечи осталась и по сей день. Еврейские праздники сегодня соблюдаются в точности так же, как и тысячи лет назад.

Шаббат

Последний день в неделе по еврейскому календарю – суббота, а не воскресенье, как мы привыкли. В Шаббат Великая Книга предполагает воздержание от работы. Считается, что этот праздник был провозглашен Богом еще во время сотворения мира и является первым Праздником Господним. «Заходит» Шаббат в пятничный вечер. Начинается праздник с ужина в кругу семьи с зажженными свечами и вкусной едой. А следующие после ужина 24 часа даны для общения с Богом. Это время встречи еженедельно неизменно и является назначенным самим Господом для встречи с его народом. В Шаббат запрещено готовить горячую еду. Поэтому если захочется насладиться теплым обедом, рекомендуется приготовить все необходимое до «захода» Шаббата и сохранять блюда в теплом состоянии до следующего дня. Вот тут у хозяек идут в ход всевозможные хитрости. Существует огромное количество еврейских блюд, которые от сохранения тепла становятся только лучше на вкус.

Отличительная особенность всех еврейских праздников – они начинаются вечером. После захода первых трех звезд. Ответить на вопрос, какой еврейский праздник важнее всего, сложно, ведь все традиции почитаются народом с одинаковым благоговением и любовью.

Candles are lit on the eve of the Jewish Sabbath («Shabbat») and on Jewish holidays.

Jewish holidays, also known as Jewish festivals or Yamim Tovim (Hebrew: ימים טובים, lit. ‘Good Days’, or singular יום טוב Yom Tov, in transliterated Hebrew []),[1] are holidays observed in Judaism and by Jews[Note 1] throughout the Hebrew calendar. They include religious, cultural and national elements, derived from three sources: biblical mitzvot («commandments»), rabbinic mandates, and the history of Judaism and the State of Israel.

Jewish holidays occur on the same dates every year in the Hebrew calendar, but the dates vary in the Gregorian. This is because the Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar calendar (based on the cycles of both the sun and moon), whereas the Gregorian is a solar calendar.

General concepts[edit]

Groupings[edit]

Certain terms are used very commonly for groups of holidays.

- The Hebrew-language term Yom Tov (יום טוב), sometimes referred to as «festival day,» usually refers to the six biblically-mandated festival dates on which all activities prohibited on Shabbat are prohibited, except for some related to food preparation.[2] These include the first and seventh days of Passover (the Feast of Unleavened Bread / the Feast of Matzot — Exodus 23:15, Deuteronomy 16:16), [first day of] Shavuot, both days of Rosh Hashanah, first day of Sukkot, and [first day of] Shemini Atzeret. By extension, outside the Land of Israel, the second-day holidays known under the rubric Yom tov sheni shel galuyot (literally, «Second Yom Tov of the Diaspora»)—including Simchat Torah—are also included in this grouping. Colloquially, Yom Kippur, a biblically-mandated date on which even food preparation is prohibited, is often included in this grouping. The tradition of keeping two days of Yom Tov in the diaspora has existed since roughly 300 BCE.

- The English-language term High Holy Days (or High Holidays) refers to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur collectively. Its Hebrew analogue, Yamim Nora’im (ימים נוראים), «Days of Awe”, is more flexible: it can refer just to those holidays, or to the Ten Days of Repentance, or to the entire penitential period, starting as early as the beginning of Elul, and (more rarely) ending as late as Shemini Atzeret.

- The term Three Pilgrimage Festivals (שלוש רגלים, shalosh regalim) refers to Passover (the Feast of Unleavened Bread / Feast of Matzot), Shavuot and Sukkot. Within this grouping Sukkot normally includes Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah.

- Ma’agal Hashana (מעגל השנה; «year cycle»), a more general term, is often used — especially in educational settings [3][4][5] — to refer to the overall study of the Jewish calendar, outlining the month by month events, with mitzvot and minhagim, and philosophical material, that occur over the course of the year.

Terminology used to describe holidays[edit]

Certain terminology is used in referring to different categories of holidays, depending on their source and their nature:

Shabbat (שבת) (Ashkenazi pron. from Yiddish shabbos), or Sabbath, is referred to by that name exclusively. Similarly, Rosh Chodesh (ראש חודש) is referred to by that name exclusively.

- Yom tov (יום טוב) (Ashkenazi pron. from Yid. yontif) (lit., «good day»): See «Groupings» above.

- Moed (מועד) («festive season»), plural moadim (מועדים), refers to any of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals of Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot. When used in comparison to Yom Tov, it refers to Chol HaMoed, the intermediate days of Passover and Sukkot.

- Ḥag or chag (חג) («festival»), plural chagim (חגים), can be used whenever yom tov or moed is. It is also used to describe Hanukkah and Purim, as well as Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israeli Independence Day) and Yom Yerushalayim (Jerusalem Day).

- Ta’anit (תענית), or, less commonly, tzom (צום), refers to a fast. These terms are generally used to describe the rabbinic fasts, although tzom is used liturgically to refer to Yom Kippur as well.[6]

«Work» on Sabbath and biblical holidays[edit]

The most notable common feature of Shabbat and the biblical festivals is the requirement to refrain from melacha on these days.[Note 2] Melacha is most commonly translated as «work»; perhaps a better translation is «creative-constructive work». Strictly speaking, Melacha is defined in Jewish law (halacha) by 39 categories of labor that were used in constructing the Tabernacle while the Jews wandered in the desert. As understood traditionally and in Orthodox Judaism:

- On Shabbat and Yom Kippur all melacha is prohibited.

- On a Yom Tov (other than Yom Kippur) which falls on a weekday, not Shabbat, most melacha is prohibited. Some melacha related to preparation of food is permitted.[Note 3][Note 4]

- On weekdays during Chol HaMoed, melacha is not prohibited per se. However, melacha should be limited to that required either to enhance the enjoyment of the remainder of the festival or to avoid great financial loss.

- On other days, there are no restrictions on melacha.[Note 5]

In principle, Conservative Judaism understands the requirement to refrain from melacha in the same way as Orthodox Judaism. In practice, Conservative rabbis frequently rule on prohibitions around melacha differently from Orthodox authorities.[9] Still, there are a number of Conservative/Masorti communities around the world where Sabbath and Festival observance fairly closely resembles Orthodox observance.[Note 6]

However, many, if not most, lay members of Conservative congregations in North America do not consider themselves Sabbath-observant, even by Conservative standards.[10] At the same time, adherents of Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism do not accept halacha, and therefore restrictions on melacha, as binding at all.[Note 7] Jews fitting any of these descriptions refrain from melacha in practice only as they personally see fit.

Shabbat and holiday work restrictions are always put aside in cases of pikuach nefesh, which is saving a human life. At the most fundamental level, if there is any possibility whatsoever that action must be taken to save a life, Shabbat restrictions are set aside immediately, and without reservation.[Note 8] Where the danger to life is present but less immediate, there is some preference to minimize violation of Shabbat work restrictions where possible. The laws in this area are complex.[11]

Second day of biblical festivals[edit]

The Torah specifies a single date on the Jewish calendar for observance of holidays. Nevertheless, festivals of biblical origin other than Shabbat and Yom Kippur are observed for two days outside the land of Israel, and Rosh Hashanah is observed for two days even inside the land of Israel.

Dates for holidays on the Jewish calendar are expressed in the Torah as «day x of month y.» Accordingly, the beginning of month y needs to be determined before the proper date of the holiday on day x can be fixed. Months in the Jewish calendar are lunar, and originally were thought to have been proclaimed by the blowing of a shofar.[12] Later, the Sanhedrin received testimony of witnesses saying they saw the new crescent moon.[Note 9] Then the Sanhedrin would inform Jewish communities away from its meeting place that it had proclaimed a new moon. The practice of observing a second festival day stemmed from delays in disseminating that information.[13]

- Rosh Hashanah. Because of holiday restrictions on travel, messengers could not even leave the seat of the Sanhedrin until the holiday was over. Inherently, there was no possible way for anyone living away from the seat of the Sanhedrin to receive news of the proclamation of the new month until messengers arrived after the fact. Accordingly, the practice emerged that Rosh Hashanah was observed on both possible days, as calculated from the previous month’s start, everywhere in the world.[14][Note 10]

- Three Pilgrimage Festivals. Sukkot and Passover fall on the 15th day of their respective months. This gave messengers two weeks to inform communities about the proclamation of the new month. Normally, they would reach most communities within the land of Israel within that time, but they might fail to reach communities farther away (such as those in Babylonia or overseas). Consequently, the practice developed that these holidays be observed for one day within Israel, but for two days (both possible days as calculated from the previous month’s start) outside Israel. This practice is known as yom tov sheni shel galuyot, «second day of festivals in exile communities».[15]

-

- For Shavuot, calculated as the fiftieth day from Passover, the above issue did not pertain directly, as the «correct» date for Passover would be known by then. Nevertheless, the Talmud applies the same rule to Shavuot, and to the Seventh Day of Passover and Shemini Atzeret, for consistency.[16]

Yom Kippur is not observed for two days anywhere because of the difficulty of maintaining a fast over two days.[Note 11]

- Shabbat is not observed based on a calendar date, but simply at intervals of seven days. Accordingly, there is never a doubt of the date of Shabbat, and it need never be observed for two days.[Note 12]

Adherents of Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism generally do not observe the second day of festivals,[17] although some do observe two days of Rosh Hashanah.[18]

Holidays of biblical and rabbinic (Talmudic) origin[edit]

Theories concerning possible non-Jewish sources for biblical holidays are beyond the scope of this article. Please see individual holiday articles, particularly Shabbat (History).

Shabbat—The Sabbath[edit]

Jewish law (halacha) accords Shabbat (שבת) the status of a holiday, a day of rest celebrated on the seventh day of each week. Jewish law defines a day as ending at either sundown or nightfall, when the next day then begins. Thus,

- Shabbat begins just before sundown Friday night. Its start is marked by the lighting of Shabbat candles and the recitation of Kiddush over a cup of wine.

- Shabbat ends at nightfall Saturday night. Its conclusion is marked by the prayer known as Havdalah.

The fundamental rituals and observances of Shabbat include:

- Reading of the Weekly Torah portion

- Abbreviation of the Amidah in the three regular daily services to eliminate requests for everyday needs

- Addition of a musaf service to the daily prayer services

- Enjoyment of three meals, often elaborate or ritualized, through the course of the day

- Restraint from performing melacha (see above).

In many ways, halakha (Jewish law) sees Shabbat as the most important holy day in the Jewish calendar.

- It is the first holiday mentioned in the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), and God was the first one to observe it (Genesis).

- The Torah reading on Shabbat has more sections of parshiot (Torah readings) than on Yom Kippur or any other Jewish holiday.

- The prescribed penalty in the Torah for a transgression of Shabbat prohibitions is death by stoning (Exodus 31), while for other holidays the penalty is (relatively) less severe.

- Observance of Shabbat is the benchmark used in halacha to determine whether an individual is a religiously observant, religiously reliable member of the community.

Rosh Chodesh—The New Month[edit]

Rosh Chodesh (ראש חודש) (lit., «head of the month») is a minor holiday or observance occurring on the first day of each month of the Jewish calendar, as well as the last day of the preceding month if it has thirty days.

- Rosh Chodesh observance during at least a portion of the period of the prophets could be fairly elaborate.[19]

- Over time there have been varying levels of observance of a custom that women are excused from certain types of work.[20]

- Fasting is normally prohibited on Rosh Chodesh.

Beyond the preceding, current observance is limited to changes in liturgy.

- In the month of Tishrei, this observance is superseded by the observance of Rosh Hashanah, a major holiday.

Related observances:

- The date of the forthcoming Rosh Chodesh is announced in synagogue on the preceding Sabbath.

- There are special prayers said upon observing the waxing moon for the first time each month.

Rosh Hashanah—The Jewish New Year[edit]

Selichot[edit]

The month of Elul that precedes Rosh Hashanah is considered to be a propitious time for repentance.[21] For this reason, additional penitential prayers called Selichot are added to the daily prayers, except on Shabbat. Sephardi Jews add these prayers each weekday during Elul. Ashkenazi Jews recite them from the last Sunday (or Saturday night) preceding Rosh Hashanah that allows at least four days of recitations.

Rosh Hashanah[edit]

- Erev Rosh Hashanah (eve of the first day): 29 Elul

- Rosh Hashanah: 1–2 Tishrei

According to oral tradition, Rosh Hashanah (ראש השנה) (lit., «Head of the Year») is the Day of Memorial or Remembrance (יום הזכרון, Yom HaZikaron),[22] and the day of judgment (יום הדין, Yom HaDin).[23] God appears in the role of King, remembering and judging each person individually according to his/her deeds, and making a decree for each person for the following year.[24]

The holiday is characterized by one specific mitzvah: blowing the shofar.[25] According to the Torah, this is the first day of the seventh month of the calendar year,[25] and marks the beginning of a ten-day period leading up to Yom Kippur. According to one of two Talmudic opinions, the creation of the world was completed on Rosh Hashanah.[26]

Morning prayer services are lengthy on Rosh Hashanah, and focus on the themes described above: majesty and judgment, remembrance, the birth of the world, and the blowing of the shofar. Ashkenazi Jews recite the brief Tashlikh prayer, a symbolic casting off of the previous year’s sins, during the afternoon of Rosh Hashanah.

The Bible specifies Rosh Hashanah as a one-day holiday,[25] but it is traditionally celebrated for two days, even within the Land of Israel. (See Second day of biblical festivals, above.)

Four New Years[edit]

The Torah itself does not use any term like «New Year» in reference to Rosh Hashanah. The Mishnah in Rosh Hashanah[27] specifies four different «New Year’s Days» for different purposes:

- 1 Tishrei (conventional «Rosh Hashanah»): «new year» for calculating calendar years, sabbatical-year (shmita) and jubilee cycles, and the age of trees for purposes of Jewish law; and for separating grain tithes.

- 15 Shevat (Tu Bishvat): «new year» for trees–i.e., their current agricultural cycle and related tithes.

- 1 Nisan: «New Year» for counting months and major festivals and for calculating the years of the reign of a Jewish king

- In biblical times, the day following 29 Adar, Year 1 of the reign of ___, would be followed by 1 Nisan, Year 2 of the reign of ___.

- In modern times, although the Jewish calendar year number changes on Rosh Hashanah, the months are still numbered from Nisan.

- The three pilgrimage festivals are always reckoned as coming in the order Passover-Shavuot-Sukkot. This can have religious law consequences even in modern times.

- 1 Elul (Rosh Hashanah LaBehema): «new year» for animal tithes.

Aseret Yemei Teshuva—Ten Days of Repentance[edit]

The first ten days of Tishrei (from the beginning of Rosh Hashana until the end of Yom Kippur) are known as the Ten Days of Repentance (עשרת ימי תשובה, Aseret Yemei Teshuva). During this time, in anticipation of Yom Kippur, it is «exceedingly appropriate»[28] for Jews to practice teshuvah (literally «return»), an examination of one’s deeds and repentance for sins one has committed against other people and God. This repentance can take the form of additional supplications, confessing one’s deeds before God, fasting, self-reflection, and an increase of involvement with, or donations to, charity.

Tzom Gedalia—Fast of Gedalia[edit]

- Tzom Gedalia: 3 Tishrei

The Fast of Gedalia (צום גדליה) is a minor Jewish fast day. It commemorates the assassination of the governor of Judah, Gedalia, which ended any level of Jewish rule following the destruction of the First Temple.

- The assassination apparently occurred on Rosh Hashanah (1 Tishrei),[29] but the fast is postponed to 3 Tishrei in respect for the holiday. It is further postponed to 4 Tishrei if 3 Tishrei is Shabbat.

As on all minor fast days, fasting from dawn to dusk is required, but other laws of mourning are not normally observed. A Torah reading is included in both the Shacharit and Mincha prayers, and a Haftarah is also included at Mincha. There are also a number of additions to the liturgy of both services.[30]

Yom Kippur—Day of Atonement[edit]

- Erev Yom Kippur: 9 Tishrei

- Yom Kippur: 10 Tishrei (begins at sunset)

Yom Kippur (יום כיפור) is the holiest day of the year for Jews.[Note 13] Its central theme is atonement and reconciliation. This is accomplished through prayer and complete fasting—including abstinence from all food and drink (including water)—by all healthy adults.[Note 14] Bathing, wearing of perfume or cologne, wearing of leather shoes, and sexual relations are some of the other prohibitions on Yom Kippur—all them designed to ensure one’s attention is completely and absolutely focused on the quest for atonement with God. Yom Kippur is also unique among holidays as having work-related restrictions identical to those of Shabbat. The fast and other prohibitions commence on 10 Tishrei at sunset—sunset being the beginning of the day in Jewish tradition.

A traditional prayer in Aramaic called Kol Nidre («All Vows») is traditionally recited just before sunset. Although often regarded as the start of the Yom Kippur evening service—to such a degree that Erev Yom Kippur («Yom Kippur Evening») is often called «Kol Nidre» (also spelled «Kol Nidrei»)—it is technically a separate tradition. This is especially so because, being recited before sunset, it is actually recited on 9 Tishrei, which is the day before Yom Kippur; it is not recited on Yom Kippur itself (on 10 Tishrei, which begins after the sun sets).

- The words of Kol Nidre differ slightly between Ashkenazic and Sephardic traditions. In both, the supplicant prays to be released from all personal vows made to God during the year, so that any unfulfilled promises made to God will be annulled and, thus, forgiven. In Ashkenazi tradition, the reference is to the coming year; in Sephardic tradition, the reference is to the year just ended. Only vows between the supplicant and God are relevant. Vows made between the supplicant and other people remain perfectly valid, since they are unaffected by the prayer.

A Tallit (four-cornered prayer shawl) is donned for evening and afternoon prayers–the only day of the year in which this is done. In traditional Ashkenazi communities, men wear the kittel throughout the day’s prayers. The prayers on Yom Kippur evening are lengthier than on any other night of the year. Once services reconvene in the morning, the services (in all traditions) are the longest of the year. In some traditional synagogues prayers run continuously from morning until nightfall, or nearly so. Two highlights of the morning prayers in traditional synagogues are the recitation of Yizkor, the prayer of remembrance, and of liturgical poems (piyyutim) describing the temple service of Yom Kippur.

Two other highlights happen late in the day. During the Minchah prayer, the haftarah reading features the entire Book of Jonah. Finally, the day concludes with Ne’ilah, a special service recited only on the day of Yom Kippur. Ne’ilah deals with the closing of the holiday, and contains a fervent final plea to God for forgiveness just before the conclusion of the fast. Yom Kippur comes to an end with the blowing of the shofar, which marks the conclusion of the fast. It is always observed as a one-day holiday, both inside and outside the boundaries of the Land of Israel.

Yom Kippur is considered, along with 15th of Av, as the happiest days of the year (Talmud Bavli—Tractate Ta’anit).[31]

Sukkot—Feast of Booths (or Tabernacles)[edit]

- Erev Sukkot: 14 Tishrei

- Sukkot: 15–21 Tishrei (22 outside Israel)

- The first day of Sukkot is (outside Israel, first two days are) full yom tov, while the remainder of Sukkot has the status of Chol Hamoed, «intermediate days».

Sukkot (סוכות or סֻכּוֹת, sukkōt) or Succoth is a seven-day festival, also known as the Feast of Booths, the Feast of Tabernacles, or just Tabernacles. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals (shalosh regalim) mentioned in the Bible. Sukkot commemorates the years that the Jews spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land, and celebrates the way in which God protected them under difficult desert conditions. The word sukkot is the plural of the Hebrew word sukkah, meaning booth. Jews are commanded to «dwell» in booths during the holiday.[32] This generally means taking meals, but some sleep in the sukkah as well, particularly in Israel. There are specific rules for constructing a sukkah.

Along with dwelling in a sukkah, the principal ritual unique to this holiday is use of the Four Species: lulav (palm), hadass (myrtle), aravah (willow) and etrog (citron).[33] On each day of the holiday other than Shabbat, these are waved in association with the recitation of Hallel in the synagogue, then walked in a procession around the synagogue called the Hoshanot.