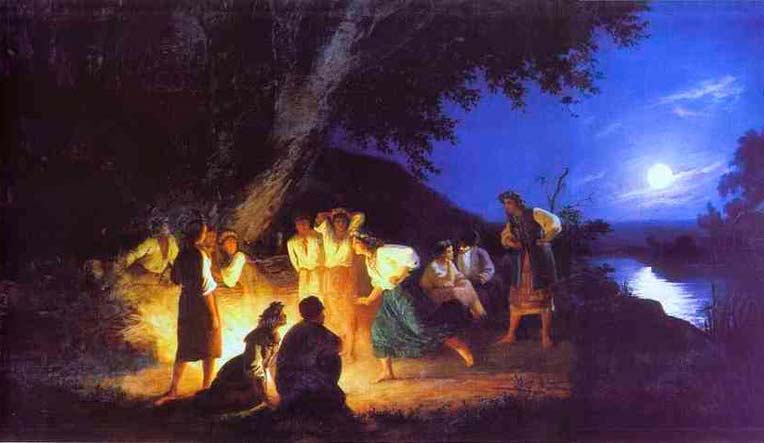

Самайн — самый важный из ирландских и кельтских языческих праздников празднуют в ночь с 31 октября на 1 ноября. Ночь Самайна у кельтов находится на стыке старого и нового года. В кельтской мифологии в ночь праздника Самайн происходит встреча двух миров — между миром людей и сверхъестественным, потусторонним Миром мёртвых, между Светом и Тьмой. Ночь Самайна может быть ужасной, так как «всё сверхъестественное устремляется вперед, готовясь захватить человеческий мир».

«Раз в году собирались все улады вместе в праздник Самайн, и длилось это собрание три дня перед Самайн, самый день Самайн и три дня после него. И пока длился праздник этот, что справлялся раз в году на равнине Муртемне, не бывало там ничего иного, как игра да гулянье, блеск да красота, пиры да угощенье. Потому-то и славилось празднование Самайн по всей Ирландии». («Болезнь Кухулина». — Пер. А. А. Смирнова // Ирландские саги. С. 195)

Празднество Самайн длилось семь дней. Центральной частью праздника являлся роскошный королевский Пир, на котором пили пиво и медовый напиток. Повсеместно устраивались весёлые пиры, всю ночь царило всеобщее опьянение в Самайн. Считалось, что языческие боги и герои умирают в ночь праздника Самайн, а король подвергался «ритуальному умерщвлению»: его топили в бочке с вином и живьём сжигали в королевском доме. Вот, что положено есть в Самайн «рыба, пиво, орехи, колбаса, огонь в весёлом стане на холме, сбитое молоко, хлеб и свежее масло» — это даёт доступ к вечности.

В праздник Самайн сюзерену платили подать и приносили дары ирландскому языческому идолу Кромм Круаху:

«Ему бесславному, должны были они

убить своих несчастных первенцев,

с множеством стенаний, опасностей,

пролить их кровь вокруг Кромм Круаха;

молока и хлебов, вот чего они тотчас просили,

треть их хороших плодов,

и велики были ужас и шум». [434 — Meyer — Lutt, The Voyage of Bran)

Речь шла не о принесении в жертву младенцев, как весьма часто полагают, но, скорее, детёнышей домашних животных.

Проповедуя друидам Ирландии, Святой Патрик обратил кельтских язычников в христианство. Согласно преданию, Святой Патрик родился в 389 году н.э. в Южном Уэльсе, в то время, эта территория входила в состав Римской Империи.

Имя «Patercius» или «Patritius» от двух латинских слов «Pater» — отец, и цевиум — «civium» — народ, «Patricivium» означает «отец народа». День Святого Патрикия в Крыму 17 марта.

Папа Римский Целестин II благословил Патрика на христианизацию Ирландии в 30-е годы IV века. За 20 лет своих проповедей в Ирландии, Святой Патрик основал 600 церквей, монастырей по всей стране.

Благодаря миссионерской деятельности Святого Патрика, в Ирландии прекратили приносить жертвы языческим богам, зажигать костры и устраивать языческие пиршества в ночь Самайна. При церквях были созданы школы, который распространяли не только христианское вероучение, но и грамоту. Святой Патрик умер в 461 г.

Папа римский Григорий IV

В 9 веке папа Григорий IV (827 — 844) утвердил в Римско-католической церкви празднование 1 ноября Дня всех святых, как официальный день поминовения всех святых церкви, всех усопших христианских верующих.

В Западном христианстве отмечается 1 ноября многими протестантскими церквями, такими как лютеранская, англиканская и методистская традиции.

Восточная православная церковь отмечает День всех святых в первое воскресенье после Пятидесятницы (=50 день после Пасхи).

В чём разница понимания праздника Дня всех святых у католиков и у православных христиан?

В представлении Русской православной церкви все почившие святые — ЖИВЫ, а в Римско-католической церкви — они МЕРТВЫ, отсюда и праздник мёртвых святых — Хэллоуин.

Языческие традиции восторжествовали в празднике Римско-католической церкви 1 ноября — Хэллоуин.

Слово Хеллоуин происходит от Allhalloweven (All+hallow — всех святых) + even (архаичное, поэтическое слово канун); шотландское сокращение от Allhallowmas (all + hallow («все святые») + -mas («месса, церковный праздник, праздник»); в др.английском: «ealra hālgena mæsse» («eall + halga + mæsse» буквально «месса всех святых»), в ср.англ.: «Alhalwemesse» (Al+halwe+messe = «всех святых месса»), англ.: «All Saints’ Day» — День всех святых.

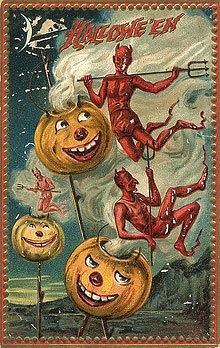

Хэллоуин в 1930 году.

В чём его суть праздника Хэллоуин?

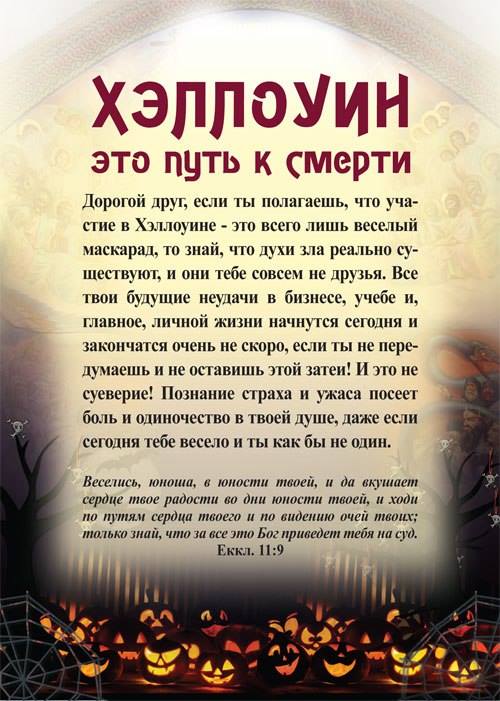

Возможно, в 9 веке это был День Всех Святых. Вполне в духе Римско-католической церкви и американской культуры, преобразовать День Всех Святых в языческий День всей нечисти. Как бы вы не относились к нечисти — она является символическим носителем Зла. То есть, вампиры, это те кто пьют кровь у людей, убивая их. Оборотни, это те, кто превращается в животных, и убивают людей. Нечисть в виде каких-то бесов, чертей, вурдалаков и прочей нечисти уж точно не приносят никакой радости людям. И вот христианское поминовение «Всех святых» превращается в ново-языческое празднество Хеллоуин (День всех умерших святых) в ночь с 31 октября на 1 ноября происходит сатанинский культ — шабаш нечисти. В костюмы нечистой силы всех рангов наряжают детей, которые должны представлять из себя вампиров, пьющих людскую кровь, вурдалаков, перегрызающих горло, чертей, бесов, отгрызающих руки-ноги… Это такая забавная игра Хеллоуина.

Не имеет значения, в кого вы там верите, само по себе это выглядит, весьма сомнительно с точки зрения нормальности или ненормальности психического здоровья. Вы говорите своему маленькому ребёнку: «Ну, ты кем будешь вампирчиком, тем, кто пьёт кровь, или тем, кто перегрызает глотку?». Вы понимаете, что это уже психическое отклонение? Так могут говорить люди сами изуродованные психически, и своё психическое уродство пытающиеся переложить на своих детей.

Почему это происходит? Потому что для Зла самое приятное – это развратить невинность, изуродовать человеческую личность в детском возрасте, когда ребёнок ещё не может видеть границу между Добром и Злом. Этими извращениями детской психики занимается современная западная цивилизация на системной основе прививается сатанизм, как норму.

Уберём метафизику. Вам нравятся серийные убийцы? А что если они придут в ваш дом? Вам нравятся насильники? А что если они вас изнасилуют? Вам нравятся те, кто считает себя вампиром? А что если они решат вам перерезать глотку, или вашей матери, или вашему ребёнку? Вам такой нечестивый человек нравится? А если нет, то почему вы наряжаете своего ребёнка вот в это сатанинское дерьмо? Зачем? Вы хотите, чтобы он стал таким? Не хотите? Тогда зачем вы идёте на поводу сатанинского Хеллоуина? Объясните! Не можете объяснить?

В большинстве случаев всё это мракобесие открывает абсолютно тупую неспособность думать, хотя очень часто этим страдают те люди, которые считают что они думающие. Неспособность анализировать простейшие вещи, начиная от самого бесовского костюма, в который ты наряжаешь ребёнка в Хеллоуин, и подражательного действия — выпью кровь, перегрызу горло, а дальше к убеждению — это хорошо и правильно убивать людей. В своём бездумном подражательстве раскрывается неспособность разбираться и понимать в сути происходящего.

Надо научиться различать, где Добро, а где Зло и научить этому детей. Если вы сами изображаете зло и ребёнка своего, который ещё ничего не понимает, наряжаете в сатанинские обличья нечисти, вы несёте в этот мир зло, потому что потом вы не объясните ребёнку, почему убивать это плохо. По мнению ребёнка это совсем не плохо, если вы с детства наряжаете его в костюм вампира, убийцы или его жертвы — труп с бело-синюшным лицом.

Обратите внимание на невероятное количество массовых серийных убийств, извращений в Америке. Почему Америка занимает первое место по массовым расстрелам, по количеству серийных маньяков, убийц и извращенцев? Откуда это взялось? Да, вот оттуда и взялось — от детских игр с нечистью. Когда ребёнка с детства приучают к сатанинским маскам и костюмам и поведению, он вырастает с уверенностью, что это хорошо, и превращает в реальность свои детские игры в убийства.

Жертвы Сатанизма в Хэллоуин

Насаждение Хеллоуина идёт в строгом соответствии с искоренением христианства и насаждением сатанизма. Сатанинский праздник требует жертвоприношений младенцев, юных, чистых и непорочных жертв. Массовая давка в центре Сеула привела к многочисленным смертям. Трагедия произошла ночью в воскресенье 29 октября 2022 года во время празднования Хеллоуина в районе Итхэвон. На Хеллоуин собралось около 100 тысяч человек, которые оказались зажаты в узком переулке. В какой-то момент в узком переулке на спуске возникла давка, и люди просто стали падать под ноги друг друга. Жертвами массовой давки и смерти от удушья стали больше 150 человек, еще 82 человека ранены, 19 из них находятся в критическом состоянии. Возраст большинства погибших — за 20 лет, в основном это девушки. Как сообщили в российском посольстве, в давке погибли четыре россиянки. Все они были моложе 30 лет.

Пришло Время сделать свой выбор между Добром и Злом.

Конгрессмен США Джейми Раскин призвал уничтожить Россию из-за православия и традиционных ценностей.

«Россия – это православная страна, исповедующая традиционные ценности. Именно поэтому она должна быть уничтожена, независимо от того, какую цену за это заплатят США», — цитирует Раскина Fox News

На сей раз мы видим сатанинский характер главного противника Святой Руси. Это не метафора, а реальные орды Антихриста. Коллективный Запад — это воплощение в человечестве самого дьявола. Отсюда его дичайшая ложь, ведь Сатана означает «клеветник», его бешеная воля к уничтожению семьи и всего человеческого рода.

Больше нет ничего промежуточного в битве между Добром и Злом, между Богом и Сатаной. Одни направо — к избранным, спасенным и спасающим, жертвенным, героическим, идущим в последний бой за Божьи ценности. Другие налево — к проклятым, одержимым, уничтожающим, зверствующим, разрушающим человеческое в человеке сатанинским силам. А это и есть Страшный Суд. Самый настоящий.

Читайте также:

| Halloween | |

|---|---|

Carving a jack-o’-lantern is a common Halloween tradition |

|

| Also called |

|

| Observed by | Western Christians and many non-Christians around the world[1] |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | First day of Allhallowtide |

| Celebrations | Trick-or-treating, costume parties, making jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, divination, apple bobbing, visiting haunted attractions. |

| Observances | Church services,[2] prayer,[3] fasting,[1] and vigil[4] |

| Date | 31 October |

| Related to | Samhain, Hop-tu-Naa, Calan Gaeaf, Allantide, Day of the Dead, Reformation Day, All Saints’ Day, Mischief Night (cf. vigil) |

Halloween or Hallowe’en (less commonly known as Allhalloween,[5] All Hallows’ Eve,[6] or All Saints’ Eve)[7] is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints’ Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide,[8] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[9][10][11][12]

One theory holds that many Halloween traditions were influenced by Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, which are believed to have pagan roots.[13][14][15][16] Some go further and suggest that Samhain may have been Christianized as All Hallow’s Day, along with its eve, by the early Church.[17] Other academics believe Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, being the vigil of All Hallow’s Day.[18][19][20][21] Celebrated in Ireland and Scotland for centuries, Irish and Scottish immigrants took many Halloween customs to North America in the 19th century,[22][23] and then through American influence Halloween had spread to other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century.[24][25]

Popular Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins or turnips into jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, and watching horror or Halloween-themed films.[26] Some people practice the Christian religious observances of All Hallows’ Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead,[27][28][29] although it is a secular celebration for others.[30][31][32] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows’ Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes.[33][34][35][36]

Etymology

The word Halloween or Hallowe’en («Saints’ evening»[37]) is of Christian origin;[38][39] a term equivalent to «All Hallows Eve» is attested in Old English.[40] The word hallowe[‘]en comes from the Scottish form of All Hallows’ Eve (the evening before All Hallows’ Day):[41] even is the Scots term for «eve» or «evening»,[42] and is contracted to e’en or een;[43] (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en became Hallowe’en.

History

Christian origins and historic customs

Halloween is thought to have influences from Christian beliefs and practices.[44][45] The English word ‘Halloween’ comes from «All Hallows’ Eve», being the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows’ Day (All Saints’ Day) on 1 November and All Souls’ Day on 2 November.[46] Since the time of the early Church,[47] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigils that began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows’.[48][44] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time when Western Christians honour all saints and pray for recently departed souls who have yet to reach Heaven. Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime.[49] In 4th-century Roman Edessa it was held on 13 May, and on 13 May 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to «St Mary and all martyrs».[50] This was the date of Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead.[51]

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III (731–741) founded an oratory in St Peter’s for the relics «of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors».[44][52] Some sources say it was dedicated on 1 November,[53] while others say it was on Palm Sunday in April 732.[54][55] By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland[56] and Northumbria were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November.[57] Alcuin of Northumbria, a member of Charlemagne’s court, may then have introduced this 1 November date in the Frankish Empire.[58] In 835, it became the official date in the Frankish Empire.[57] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea,[57] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.[59] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of ‘dying’ in nature.[57][59] It is also suggested the change was made on the «practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it», and perhaps because of public health concerns over Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives during Rome’s sultry summers.[60][44]

On All Hallows’ Eve, Christians in some parts of the world visit cemeteries to pray and place flowers and candles on the graves of their loved ones.[61] Top: Christians in Bangladesh lighting candles on the headstone of a relative. Bottom: Lutheran Christians praying and lighting candles in front of the central crucifix of a graveyard.

By the end of the 12th century, the celebration had become known as the holy days of obligation in Western Christianity and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for souls in purgatory. It was also «customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls».[62] The Allhallowtide custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls,[63] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating.[64] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[65] and was found in parts of England, Wales, Flanders, Bavaria and Austria.[66] Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers’ friends and relatives. This was called «souling».[65][67][68] Soul cakes were also offered for the souls themselves to eat,[66] or the ‘soulers’ would act as their representatives.[69] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating they were baked as alms.[70] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593).[71] While souling, Christians would carry «lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips», which could have originally represented souls of the dead;[72][73] jack-o’-lanterns were used to ward off evil spirits.[74][75] On All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day during the 19th century, candles were lit in homes in Ireland,[76] Flanders, Bavaria, and in Tyrol, where they were called «soul lights»,[77] that served «to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes».[78] In many of these places, candles were also lit at graves on All Souls’ Day.[77] In Brittany, libations of milk were poured on the graves of kinfolk,[66] or food would be left overnight on the dinner table for the returning souls;[77] a custom also found in Tyrol and parts of Italy.[79][77]

Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh linked the wearing of costumes to the belief in vengeful ghosts: «It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints’ Day, and All Hallows’ Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes».[80] In the Middle Ages, churches in Europe that were too poor to display relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[81][82] Some Christians observe this custom at Halloween today.[83] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom.[84] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed «that once a year, on Hallowe’en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival» known as the danse macabre, which was often depicted in church decoration.[85] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that the danse macabre urged Christians «not to forget the end of all earthly things».[86] The danse macabre was sometimes enacted in European village pageants and court masques, with people «dressing up as corpses from various strata of society», and this may be the origin of Halloween costume parties.[87][88][89][72]

In Britain, these customs came under attack during the Reformation, as Protestants berated purgatory as a «popish» doctrine incompatible with the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. State-sanctioned ceremonies associated with the intercession of saints and prayer for souls in purgatory were abolished during the Elizabethan reform, though All Hallow’s Day remained in the English liturgical calendar to «commemorate saints as godly human beings».[90] For some Nonconformist Protestants, the theology of All Hallows’ Eve was redefined; «souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits».[91] Other Protestants believed in an intermediate state known as Hades (Bosom of Abraham).[92] In some localities, Catholics and Protestants continued souling, candlelit processions, or ringing church bells for the dead;[46][93] the Anglican church eventually suppressed this bell-ringing.[94] Mark Donnelly, a professor of medieval archaeology, and historian Daniel Diehl write that «barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth».[95] After 1605, Hallowtide was eclipsed in England by Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), which appropriated some of its customs.[96] In England, the ending of official ceremonies related to the intercession of saints led to the development of new, unofficial Hallowtide customs. In 18th–19th century rural Lancashire, Catholic families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows’ Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen’lay.[97] There was a similar custom in Hertfordshire, and the lighting of ‘tindle’ fires in Derbyshire.[98] Some suggested these ‘tindles’ were originally lit to «guide the poor souls back to earth».[99] In Scotland and Ireland, old Allhallowtide customs that were at odds with Reformed teaching were not suppressed as they «were important to the life cycle and rites of passage of local communities» and curbing them would have been difficult.[22]

In parts of Italy until the 15th century, families left a meal out for the ghosts of relatives, before leaving for church services.[79] In 19th-century Italy, churches staged «theatrical re-enactments of scenes from the lives of the saints» on All Hallow’s Day, with «participants represented by realistic wax figures».[79] In 1823, the graveyard of Holy Spirit Hospital in Rome presented a scene in which bodies of those who recently died were arrayed around a wax statue of an angel who pointed upward towards heaven.[79] In the same country, «parish priests went house-to-house, asking for small gifts of food which they shared among themselves throughout that night».[79] In Spain, they continue to bake special pastries called «bones of the holy» (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and set them on graves.[100] At cemeteries in Spain and France, as well as in Latin America, priests lead Christian processions and services during Allhallowtide, after which people keep an all night vigil.[101] In 19th-century San Sebastián, there was a procession to the city cemetery at Allhallowtide, an event that drew beggars who «appeal[ed] to the tender recollectons of one’s deceased relations and friends» for sympathy.[102]

Gaelic folk influence

Today’s Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have pagan roots.[103] Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that «there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived».[104] The origins of Halloween customs are typically linked to the Gaelic festival Samhain.[105]

Samhain is one of the quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and has been celebrated on 31 October – 1 November[106] in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[107][108] A kindred festival has been held by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning «first day of winter». For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival begins the evening before 1 November by modern reckoning.[109] Samhain is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature. The names have been used by historians to refer to Celtic Halloween customs up until the 19th century,[110] and are still the Gaelic and Welsh names for Halloween.

Snap-Apple Night, painted by Daniel Maclise in 1833, shows people feasting and playing divination games on Halloween in Ireland.[111]

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the ‘darker half’ of the year.[112][113] It was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí, the ‘spirits’ or ‘fairies’, could more easily come into this world and were particularly active.[114][115] Most scholars see them as «degraded versions of ancient gods […] whose power remained active in the people’s minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs».[116] They were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.[117][118] At Samhain, the Aos Sí were appeased to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for them.[119][120][121] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality.[122] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[123] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures.[66] In 19th century Ireland, «candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin».[124]

Throughout Ireland and Britain, especially in the Celtic-speaking regions, the household festivities included divination rituals and games intended to foretell one’s future, especially regarding death and marriage.[125] Apples and nuts were often used, and customs included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others.[126] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke, and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.[112] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[110] It is suggested the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun and held back the decay and darkness of winter.[123][127][128] They were also used for divination and to ward off evil spirits.[74] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes.[129] In Wales, bonfires were also lit to «prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth».[130] Later, these bonfires «kept away the devil».[131]

A plaster cast of a traditional Irish Halloween turnip (rutabaga) lantern on display in the Museum of Country Life, Ireland[132]

From at least the 16th century,[133] the festival included mumming and guising in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales.[134] This involved people going house-to-house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting verses or songs in exchange for food. It may have originally been a tradition whereby people impersonated the Aos Sí, or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf, similar to ‘souling’. Impersonating these beings, or wearing a disguise, was also believed to protect oneself from them.[135] In parts of southern Ireland, the guisers included a hobby horse. A man dressed as a Láir Bhán (white mare) led youths house-to-house reciting verses – some of which had pagan overtones – in exchange for food. If the household donated food it could expect good fortune from the ‘Muck Olla’; not doing so would bring misfortune.[136] In Scotland, youths went house-to-house with masked, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.[134] F. Marian McNeill suggests the ancient festival included people in costume representing the spirits, and that faces were marked or blackened with ashes from the sacred bonfire.[133] In parts of Wales, men went about dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod.[134] In the late 19th and early 20th century, young people in Glamorgan and Orkney cross-dressed.[134]

Elsewhere in Europe, mumming was part of other festivals, but in the Celtic-speaking regions, it was «particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers».[134] From at least the 18th century, «imitating malignant spirits» led to playing pranks in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Wearing costumes and playing pranks at Halloween did not spread to England until the 20th century.[134] Pranksters used hollowed-out turnips or mangel wurzels as lanterns, often carved with grotesque faces.[134] By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits,[134] or used to ward off evil spirits.[137][138] They were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century,[134] as well as in Somerset (see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of Britain and became generally known as jack-o’-lanterns.[134]

Spread to North America

Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott write that Anglican colonists in the southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland «recognized All Hallow’s Eve in their church calendars»,[140][141] although the Puritans of New England strongly opposed the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas.[142] Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America.[22]

It was not until after mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in America.[22] Most American Halloween traditions were inherited from the Irish and Scots,[23][143] though «In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside».[144] Originally confined to these immigrant communities, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and was celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial, and religious backgrounds by the early 20th century.[145] Then, through American influence, these Halloween traditions spread to many other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century, including to mainland Europe and some parts of the Far East.[24][25][146]

Symbols

Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time. Jack-o’-lanterns are traditionally carried by guisers on All Hallows’ Eve in order to frighten evil spirits.[73][147] There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o’-lantern,[148] which in folklore is said to represent a «soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell»:[149]

On route home after a night’s drinking, Jack encounters the Devil and tricks him into climbing a tree. A quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil. Jack strikes a bargain that Satan can never claim his soul. After a life of sin, drink, and mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. Keeping his promise, the Devil refuses to let Jack into hell and throws a live coal straight from the fires of hell at him. It was a cold night, so Jack places the coal in a hollowed out turnip to stop it from going out, since which time Jack and his lantern have been roaming looking for a place to rest.[150]

In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween,[151][152] but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger, making it easier to carve than a turnip.[151] The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837[153] and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century.[154]

The modern imagery of Halloween comes from many sources, including Christian eschatology, national customs, works of Gothic and horror literature (such as the novels Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus and Dracula) and classic horror films such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932).[155][156] Imagery of the skull, a reference to Golgotha in the Christian tradition, serves as «a reminder of death and the transitory quality of human life» and is consequently found in memento mori and vanitas compositions;[157] skulls have therefore been commonplace in Halloween, which touches on this theme.[158] Traditionally, the back walls of churches are «decorated with a depiction of the Last Judgment, complete with graves opening and the dead rising, with a heaven filled with angels and a hell filled with devils», a motif that has permeated the observance of this triduum.[159] One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; «What fearfu’ pranks ensue!», as well as the supernatural associated with the night, «bogles» (ghosts),[160] influencing Robert Burns’ «Halloween» (1785).[161] Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters.[162] Black cats, which have been long associated with witches, are also a common symbol of Halloween. Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween’s traditional colors.[163]

Trick-or-treating and guising

Trick-or-treaters in Sweden

Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. Children go in costume from house to house, asking for treats such as candy or sometimes money, with the question, «Trick or treat?» The word «trick» implies a «threat» to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.[64] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling.[164] John Pymm wrote that «many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church.»[165] These feast days included All Hallows’ Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.[166][167] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe,[168] involved masked persons in fancy dress who «paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence».[169]

Girl in a Halloween costume in 1928, Ontario, Canada, the same province where the Scottish Halloween custom of guising was first recorded in North America

In England, from the medieval period,[170] up until the 1930s,[171] people practiced the Christian custom of souling on Halloween, which involved groups of soulers, both Protestant and Catholic,[93] going from parish to parish, begging the rich for soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the souls of the givers and their friends.[67] In the Philippines, the practice of souling is called Pangangaluluwa and is practiced on All Hallow’s Eve among children in rural areas.[26] People drape themselves in white cloths to represent souls and then visit houses, where they sing in return for prayers and sweets.[26]

In Scotland and Ireland, guising – children disguised in costume going from door to door for food or coins – is a traditional Halloween custom.[172] It is recorded in Scotland at Halloween in 1895 where masqueraders in disguise carrying lanterns made out of scooped out turnips, visit homes to be rewarded with cakes, fruit, and money.[152][173] In Ireland, the most popular phrase for kids to shout (until the 2000s) was «Help the Halloween Party».[172] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America was first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, reported children going «guising» around the neighborhood.[174]

American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe’en (1919), and references souling in the chapter «Hallowe’en in America».[175] In her book, Kelley touches on customs that arrived from across the Atlantic; «Americans have fostered them, and are making this an occasion something like what it must have been in its best days overseas. All Halloween customs in the United States are borrowed directly or adapted from those of other countries».[176]

While the first reference to «guising» in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.[177] The earliest known use in print of the term «trick or treat» appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald, of Alberta, Canada.[178]

The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating.[179] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice in North America until the 1930s, with the first US appearances of the term in 1934,[180] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.[181]

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgating), occurs when «children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot», or sometimes, a school parking lot.[100][182] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme,[183] such as those of children’s literature, movies, scripture, and job roles.[184] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it «solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart».[185][186]

Costumes

Halloween costumes were traditionally modeled after figures such as vampires, ghosts, skeletons, scary looking witches, and devils.[64] Over time, the costume selection extended to include popular characters from fiction, celebrities, and generic archetypes such as ninjas and princesses.

Halloween shop in Derry, Northern Ireland, selling masks

Dressing up in costumes and going «guising» was prevalent in Scotland and Ireland at Halloween by the late 19th century.[152] A Scottish term, the tradition is called «guising» because of the disguises or costumes worn by the children.[173] In Ireland and Scotland, the masks are known as ‘false faces’,[38][187] a term recorded in Ayr, Scotland in 1890 by a Scot describing guisers: «I had mind it was Halloween . . . the wee callans were at it already, rinning aboot wi’ their fause-faces (false faces) on and their bits o’ turnip lanthrons (lanterns) in their haun (hand)».[38] Costuming became popular for Halloween parties in the US in the early 20th century, as often for adults as for children, and when trick-or-treating was becoming popular in Canada and the US in the 1920s and 1930s.[178][188]

Eddie J. Smith, in his book Halloween, Hallowed is Thy Name, offers a religious perspective to the wearing of costumes on All Hallows’ Eve, suggesting that by dressing up as creatures «who at one time caused us to fear and tremble», people are able to poke fun at Satan «whose kingdom has been plundered by our Saviour». Images of skeletons and the dead are traditional decorations used as memento mori.[189][190]

«Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF» is a fundraising program to support UNICEF,[64] a United Nations Programme that provides humanitarian aid to children in developing countries. Started as a local event in a Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood in 1950 and expanded nationally in 1952, the program involves the distribution of small boxes by schools (or in modern times, corporate sponsors like Hallmark, at their licensed stores) to trick-or-treaters, in which they can solicit small-change donations from the houses they visit. It is estimated that children have collected more than $118 million for UNICEF since its inception. In Canada, in 2006, UNICEF decided to discontinue their Halloween collection boxes, citing safety and administrative concerns; after consultation with schools, they instead redesigned the program.[191][192]

The yearly New York’s Village Halloween Parade was begun in 1974; it is the world’s largest Halloween parade and America’s only major nighttime parade, attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million spectators, and a worldwide television audience.[193]

Since the late 2010s, ethnic stereotypes as costumes have increasingly come under scrutiny in the United States.[194] Such and other potentially offensive costumes have been met with increasing public disapproval.[195][196]

Pet costumes

According to a 2018 report from the National Retail Federation, 30 million Americans will spend an estimated $480 million on Halloween costumes for their pets in 2018. This is up from an estimated $200 million in 2010. The most popular costumes for pets are the pumpkin, followed by the hot dog, and the bumblebee in third place.[197]

Games and other activities

In this 1904 Halloween greeting card, divination is depicted: the young woman looking into a mirror in a darkened room hopes to catch a glimpse of her future husband.

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one’s future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a «rare few» in rural communities as they were considered to be «deadly serious» practices.[198] In recent centuries, these divination games have been «a common feature of the household festivities» in Ireland and Britain.[125] They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom.[199] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona.[64]

Children bobbing for apples at Hallowe’en

The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th–20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today.

One common game is apple bobbing or dunking (which may be called «dooking» in Scotland)[200] in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face. Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth.[201]

Image from the Book of Hallowe’en (1919) showing several Halloween activities, such as nut roasting

Several of the traditional activities from Ireland and Britain involve foretelling one’s future partner or spouse. An apple would be peeled in one long strip, then the peel tossed over the shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse’s name.[202][203] Two hazelnuts would be roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desire. If the nuts jump away from the heat, it is a bad sign, but if the nuts roast quietly it foretells a good match.[204][205] A salty oatmeal bannock would be baked; the person would eat it in three bites and then go to bed in silence without anything to drink. This is said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst.[206] Unmarried women were told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror.[207] The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards[208] from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Another popular Irish game was known as púicíní («blindfolds»); a person would be blindfolded and then would choose between several saucers. The item in the saucer would provide a hint as to their future: a ring would mean that they would marry soon; clay, that they would die soon, perhaps within the year; water, that they would emigrate; rosary beads, that they would take Holy Orders (become a nun, priest, monk, etc.); a coin, that they would become rich; a bean, that they would be poor.[209][210][211][212] The game features prominently in the James Joyce short story «Clay» (1914).[213][214][215]

In Ireland and Scotland, items would be hidden in food – usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or colcannon – and portions of it served out at random. A person’s future would be foretold by the item they happened to find; for example, a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth.[216]

Up until the 19th century, the Halloween bonfires were also used for divination in parts of Scotland, Wales and Brittany. When the fire died down, a ring of stones would be laid in the ashes, one for each person. In the morning, if any stone was mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year.[110]

Telling ghost stories, listening to Halloween-themed songs and watching horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties. Episodes of television series and Halloween-themed specials (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before Halloween, while new horror films are often released before Halloween to take advantage of the holiday.

Haunted attractions

Humorous tombstones in front of a house in California

Haunted attractions are entertainment venues designed to thrill and scare patrons. Most attractions are seasonal Halloween businesses that may include haunted houses, corn mazes, and hayrides,[217] and the level of sophistication of the effects has risen as the industry has grown.

The first recorded purpose-built haunted attraction was the Orton and Spooner Ghost House, which opened in 1915 in Liphook, England. This attraction actually most closely resembles a carnival fun house, powered by steam.[218][219] The House still exists, in the Hollycombe Steam Collection.

It was during the 1930s, about the same time as trick-or-treating, that Halloween-themed haunted houses first began to appear in America. It was in the late 1950s that haunted houses as a major attraction began to appear, focusing first on California. Sponsored by the Children’s Health Home Junior Auxiliary, the San Mateo Haunted House opened in 1957. The San Bernardino Assistance League Haunted House opened in 1958. Home haunts began appearing across the country during 1962 and 1963. In 1964, the San Manteo Haunted House opened, as well as the Children’s Museum Haunted House in Indianapolis.[220]

The haunted house as an American cultural icon can be attributed to the opening of The Haunted Mansion in Disneyland on 12 August 1969.[221] Knott’s Berry Farm began hosting its own Halloween night attraction, Knott’s Scary Farm, which opened in 1973.[222] Evangelical Christians adopted a form of these attractions by opening one of the first «hell houses» in 1972.[223]

The first Halloween haunted house run by a nonprofit organization was produced in 1970 by the Sycamore-Deer Park Jaycees in Clifton, Ohio. It was cosponsored by WSAI, an AM radio station broadcasting out of Cincinnati, Ohio. It was last produced in 1982.[224] Other Jaycees followed suit with their own versions after the success of the Ohio house. The March of Dimes copyrighted a «Mini haunted house for the March of Dimes» in 1976 and began fundraising through their local chapters by conducting haunted houses soon after. Although they apparently quit supporting this type of event nationally sometime in the 1980s, some March of Dimes haunted houses have persisted until today.[225]

On the evening of 11 May 1984, in Jackson Township, New Jersey, the Haunted Castle (Six Flags Great Adventure) caught fire. As a result of the fire, eight teenagers perished.[226] The backlash to the tragedy was a tightening of regulations relating to safety, building codes and the frequency of inspections of attractions nationwide. The smaller venues, especially the nonprofit attractions, were unable to compete financially, and the better funded commercial enterprises filled the vacuum.[227][228] Facilities that were once able to avoid regulation because they were considered to be temporary installations now had to adhere to the stricter codes required of permanent attractions.[229][230][231]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, theme parks entered the business seriously. Six Flags Fright Fest began in 1986 and Universal Studios Florida began Halloween Horror Nights in 1991. Knott’s Scary Farm experienced a surge in attendance in the 1990s as a result of America’s obsession with Halloween as a cultural event. Theme parks have played a major role in globalizing the holiday. Universal Studios Singapore and Universal Studios Japan both participate, while Disney now mounts Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party events at its parks in Paris, Hong Kong and Tokyo, as well as in the United States.[232] The theme park haunts are by far the largest, both in scale and attendance.[233]

Food

Pumpkins for sale during Halloween

On All Hallows’ Eve, many Western Christian denominations encourage abstinence from meat, giving rise to a variety of vegetarian foods associated with this day.[234]

Because in the Northern Hemisphere Halloween comes in the wake of the yearly apple harvest, candy apples (known as toffee apples outside North America), caramel apples or taffy apples are common Halloween treats made by rolling whole apples in a sticky sugar syrup, sometimes followed by rolling them in nuts.

At one time, candy apples were commonly given to trick-or-treating children, but the practice rapidly waned in the wake of widespread rumors that some individuals were embedding items like pins and razor blades in the apples in the United States.[235] While there is evidence of such incidents,[236] relative to the degree of reporting of such cases, actual cases involving malicious acts are extremely rare and have never resulted in serious injury. Nonetheless, many parents assumed that such heinous practices were rampant because of the mass media. At the peak of the hysteria, some hospitals offered free X-rays of children’s Halloween hauls in order to find evidence of tampering. Virtually all of the few known candy poisoning incidents involved parents who poisoned their own children’s candy.[237]

One custom that persists in modern-day Ireland is the baking (or more often nowadays, the purchase) of a barmbrack (Irish: báirín breac), which is a light fruitcake, into which a plain ring, a coin, and other charms are placed before baking.[238] It is considered fortunate to be the lucky one who finds it.[238] It has also been said that those who get a ring will find their true love in the ensuing year. This is similar to the tradition of king cake at the festival of Epiphany.

List of foods associated with Halloween:

- Barmbrack (Ireland)

- Bonfire toffee (Great Britain)

- Candy apples/toffee apples (Great Britain and Ireland)

- Candy apples, candy corn, candy pumpkins (North America)

- Chocolate

- Monkey nuts (peanuts in their shells) (Ireland and Scotland)

- Caramel apples

- Caramel corn

- Colcannon (Ireland; see below)

- Halloween cake

- Sweets/candy

- Novelty candy shaped like skulls, pumpkins, bats, worms, etc.

- Roasted pumpkin seeds

- Roasted sweet corn

- Soul cakes

- Pumpkin Pie

Christian religious observances

The Vigil of All Hallows’ is being celebrated at an Episcopal Christian church on Hallowe’en

On Hallowe’en (All Hallows’ Eve), in Poland, believers were once taught to pray out loud as they walk through the forests in order that the souls of the dead might find comfort; in Spain, Christian priests in tiny villages toll their church bells in order to remind their congregants to remember the dead on All Hallows’ Eve.[239] In Ireland, and among immigrants in Canada, a custom includes the Christian practice of abstinence, keeping All Hallows’ Eve as a meat-free day and serving pancakes or colcannon instead.[240] In Mexico children make an altar to invite the return of the spirits of dead children (angelitos).[241]

The Christian Church traditionally observed Hallowe’en through a vigil. Worshippers prepared themselves for feasting on the following All Saints’ Day with prayers and fasting.[242] This church service is known as the Vigil of All Hallows or the Vigil of All Saints;[243][244] an initiative known as Night of Light seeks to further spread the Vigil of All Hallows throughout Christendom.[245][246] After the service, «suitable festivities and entertainments» often follow, as well as a visit to the graveyard or cemetery, where flowers and candles are often placed in preparation for All Hallows’ Day.[247][248] In Finland, because so many people visit the cemeteries on All Hallows’ Eve to light votive candles there, they «are known as valomeri, or seas of light».[249]

Today, Christian attitudes towards Halloween are diverse. In the Anglican Church, some dioceses have chosen to emphasize the Christian traditions associated with All Hallow’s Eve.[250][251] Some of these practices include praying, fasting and attending worship services.[1][2][3]

O LORD our God, increase, we pray thee, and multiply upon us the gifts of thy grace: that we, who do prevent the glorious festival of all thy Saints, may of thee be enabled joyfully to follow them in all virtuous and godly living. Through Jesus Christ, Our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen. —Collect of the Vigil of All Saints, The Anglican Breviary[252]

Votive candles in the Halloween section of Walmart

Other Protestant Christians also celebrate All Hallows’ Eve as Reformation Day, a day to remember the Protestant Reformation, alongside All Hallow’s Eve or independently from it.[253] This is because Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-five Theses to All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on All Hallows’ Eve.[254] Often, «Harvest Festivals» or «Reformation Festivals» are held on All Hallows’ Eve, in which children dress up as Bible characters or Reformers.[255] In addition to distributing candy to children who are trick-or-treating on Hallowe’en, many Christians also provide gospel tracts to them. One organization, the American Tract Society, stated that around 3 million gospel tracts are ordered from them alone for Hallowe’en celebrations.[256] Others order Halloween-themed Scripture Candy to pass out to children on this day.[257][258]

Belizean children dressed up as Biblical figures and Christian saints

Some Christians feel concerned about the modern celebration of Halloween because they feel it trivializes – or celebrates – paganism, the occult, or other practices and cultural phenomena deemed incompatible with their beliefs.[259] Father Gabriele Amorth, an exorcist in Rome, has said, «if English and American children like to dress up as witches and devils on one night of the year that is not a problem. If it is just a game, there is no harm in that.»[260] In more recent years, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston has organized a «Saint Fest» on Halloween.[261] Similarly, many contemporary Protestant churches view Halloween as a fun event for children, holding events in their churches where children and their parents can dress up, play games, and get candy for free. To these Christians, Halloween holds no threat to the spiritual lives of children: being taught about death and mortality, and the ways of the Celtic ancestors actually being a valuable life lesson and a part of many of their parishioners’ heritage.[262] Christian minister Sam Portaro wrote that Halloween is about using «humor and ridicule to confront the power of death».[263]

In the Roman Catholic Church, Halloween’s Christian connection is acknowledged, and Halloween celebrations are common in many Catholic parochial schools in the United States.[264][265] Many fundamentalist and evangelical churches use «Hell houses» and comic-style tracts in order to make use of Halloween’s popularity as an opportunity for evangelism.[266] Others consider Halloween to be completely incompatible with the Christian faith due to its putative origins in the Festival of the Dead celebration.[267] Indeed, even though Eastern Orthodox Christians observe All Hallows’ Day on the First Sunday after Pentecost, The Eastern Orthodox Church recommends the observance of Vespers or a Paraklesis on the Western observance of All Hallows’ Eve, out of the pastoral need to provide an alternative to popular celebrations.[268]

Analogous celebrations and perspectives

Judaism

According to Alfred J. Kolatch in the Second Jewish Book of Why, in Judaism, Halloween is not permitted by Jewish Halakha because it violates Leviticus 18:3, which forbids Jews from partaking in gentile customs. Many Jews observe Yizkor communally four times a year, which is vaguely similar to the observance of Allhallowtide in Christianity, in the sense that prayers are said for both «martyrs and for one’s own family».[269] Nevertheless, many American Jews celebrate Halloween, disconnected from its Christian origins.[270] Reform Rabbi Jeffrey Goldwasser has said that «There is no religious reason why contemporary Jews should not celebrate Halloween» while Orthodox Rabbi Michael Broyde has argued against Jews’ observing the holiday.[271] Purim has sometimes been compared to Halloween, in part due to some observants wearing costumes, especially of Biblical figures described in the Purim narrative.[272]

Islam

Sheikh Idris Palmer, author of A Brief Illustrated Guide to Understanding Islam, has ruled that Muslims should not participate in Halloween, stating that «participation in Halloween is worse than participation in Christmas, Easter, … it is more sinful than congratulating the Christians for their prostration to the crucifix».[273] It has also been ruled to be haram by the National Fatwa Council of Malaysia because of its alleged pagan roots stating «Halloween is celebrated using a humorous theme mixed with horror to entertain and resist the spirit of death that influence humans».[274][275] Dar Al-Ifta Al-Missriyyah disagrees provided the celebration is not referred to as an ‘eid’ and that behaviour remains in line with Islamic principles.[276]

Hinduism

Hindus remember the dead during the festival of Pitru Paksha, during which Hindus pay homage to and perform a ceremony «to keep the souls of their ancestors at rest». It is celebrated in the Hindu month of Bhadrapada, usually in mid-September.[277] The celebration of the Hindu festival Diwali sometimes conflicts with the date of Halloween; but some Hindus choose to participate in the popular customs of Halloween.[278] Other Hindus, such as Soumya Dasgupta, have opposed the celebration on the grounds that Western holidays like Halloween have «begun to adversely affect our indigenous festivals».[279]

Neopaganism

There is no consistent rule or view on Halloween amongst those who describe themselves as Neopagans or Wiccans. Some Neopagans do not observe Halloween, but instead observe Samhain on 1 November,[280] some neopagans do enjoy Halloween festivities, stating that one can observe both «the solemnity of Samhain in addition to the fun of Halloween». Some neopagans are opposed to the celebration of Hallowe’en, stating that it «trivializes Samhain»,[281] and «avoid Halloween, because of the interruptions from trick or treaters».[282] The Manitoban writes that «Wiccans don’t officially celebrate Halloween, despite the fact that 31 Oct. will still have a star beside it in any good Wiccan’s day planner. Starting at sundown, Wiccans celebrate a holiday known as Samhain. Samhain actually comes from old Celtic traditions and is not exclusive to Neopagan religions like Wicca. While the traditions of this holiday originate in Celtic countries, modern day Wiccans don’t try to historically replicate Samhain celebrations. Some traditional Samhain rituals are still practised, but at its core, the period is treated as a time to celebrate darkness and the dead – a possible reason why Samhain can be confused with Halloween celebrations.»[280]

Geography

Halloween display in Kobe, Japan

The traditions and importance of Halloween vary greatly among countries that observe it. In Scotland and Ireland, traditional Halloween customs include children dressing up in costume going «guising», holding parties, while other practices in Ireland include lighting bonfires, and having firework displays.[172][283][284] In Brittany children would play practical jokes by setting candles inside skulls in graveyards to frighten visitors.[285] Mass transatlantic immigration in the 19th century popularized Halloween in North America, and celebration in the United States and Canada has had a significant impact on how the event is observed in other nations.[172] This larger North American influence, particularly in iconic and commercial elements, has extended to places such as Brazil, Ecuador, Chile,[286] Australia,[287] New Zealand,[288] (most) continental Europe, Finland,[289] Japan, and other parts of East Asia.[25]

See also

- Campfire story

- Devil’s Night

- Dziady

- Ghost Festival

- Naraka Chaturdashi

- Kekri

- List of fiction works about Halloween

- List of films set around Halloween

- List of Halloween television specials

- Martinisingen

- Neewollah

- St. John’s Eve

- Walpurgis Night

- Will-o’-the-wisp

- English festivals

References

- ^ a b c «BBC – Religions – Christianity: All Hallows’ Eve». British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2010. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

It is widely believed that many Hallowe’en traditions have evolved from an ancient Celtic festival called Samhain which was Christianised by the early Church…. All Hallows’ Eve falls on 31st October each year, and is the day before All Hallows’ Day, also known as All Saints’ Day in the Christian calendar. The Church traditionally held a vigil on All Hallows’ Eve when worshippers would prepare themselves with prayers and fasting prior to the feast day itself. The name derives from the Old English ‘hallowed’ meaning holy or sanctified and is now usually contracted to the more familiar word Hallowe’en. …However, there are supporters of the view that Hallowe’en, as the eve of All Saints’ Day, originated entirely independently of Samhain …

- ^ a b «Service for All Hallows’ Eve». The Book of Occasional Services 2003. Church Publishing, Inc. 2004. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-89869-409-3.

This service may be used on the evening of October 31, known as All Hallows’ Eve. Suitable festivities and entertainments may take place before or after this service, and a visit may be made to a cemetery or burial place.

- ^ a b Anne E. Kitch (2004). The Anglican Family Prayer Book. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8192-2565-8. Archived from the original on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

All Hallow’s Eve, which later became known as Halloween, is celebrated on the night before All Saints’ Day, November 1. Use this simple prayer service in conjunction with Halloween festivities to mark the Christian roots of this festival.

- ^ The Paulist Liturgy Planning Guide. Paulist Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-8091-4414-3. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

Rather than compete, liturgy planners would do well to consider ways of including children in the celebration of these vigil Masses. For example, children might be encouraged to wear Halloween costumes representing their patron saint or their favorite saint, clearly adding a new level of meaning to the Halloween celebrations and the celebration of All Saints’ Day.

- ^ Palmer, Abram Smythe (1882). Folk-etymology. Johnson Reprint. p. 6.

- ^ Elwell, Walter A. (2001). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academic. p. 533. ISBN 978-0-8010-2075-9.

Halloween (All Hallows Eve). The name given to October 31, the eve of the Christian festival of All Saints Day (November 1).

- ^ «NEDCO Producers’ Guide». 31–33. Northeast Dairy Cooperative Federation. 1973.

Originally celebrated as the night before All Saints’ Day, Christians chose November first to honor their many saints. The night before was called All Saints’ Eve or hallowed eve meaning holy evening.

- ^ «Tudor Hallowtide». National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

Hallowtide covers the three days – 31 October (All-Hallows Eve or Hallowe’en), 1 November (All Saints) and 2 November (All Souls).

- ^ Hughes, Rebekkah (29 October 2014). «Happy Hallowe’en Surrey!» (PDF). The Stag. University of Surrey. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Halloween or Hallowe’en, is the yearly celebration on October 31st that signifies the first day of Allhallowtide, being the time to remember the dead, including martyrs, saints and all faithful departed Christians.

- ^ Davis, Kenneth C. (29 December 2009). Don’t Know Much About Mythology: Everything You Need to Know About the Greatest Stories in Human History but Never Learned. HarperCollins. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-06-192575-7.

- ^ «All Faithful Departed, Commemoration of».

- ^ «The Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed (All Souls’ Day) — November 02, 2021 — Liturgical Calendar». www.catholicculture.org.

- ^ Smith, Bonnie G. (2004). Women’s History in Global Perspective. University of Illinois Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-252-02931-8. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

The pre-Christian observance obviously influenced the Christian celebration of All Hallows’ Eve, just as the Taoist festival affected the newer Buddhist Ullambana festival. Although the Christian version of All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days came to emphasize prayers for the dead, visits to graves, and the role of the living assuring the safe passage to heaven of their departed loved ones, older notions never disappeared.

- ^ Nicholas Rogers (2002). Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516896-9. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

Halloween and the Day of the Dead share a common origin in the Christian commemoration of the dead on All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day. But both are thought to embody strong pre-Christian beliefs. In the case of Halloween, the Celtic celebration of Samhain is critical to its pagan legacy, a claim that has been foregrounded in recent years by both new-age enthusiasts and the evangelical Right.

- ^ Austrian information. 1965. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

The feasts of Hallowe’en, or All Hallows Eve and the devotions to the dead on All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day are both mixtures of old Celtic, Druid and other pagan customs intertwined with Christian practice.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopædia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. 1999. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

Halloween, also called All Hallows’ Eve, holy or hallowed evening observed on October 31, the eve of All Saints’ Day. The Irish pre-Christian observances influenced the Christian festival of All Hallows’ Eve, celebrated on the same date.

- ^ Roberts, Brian K. (1987). The Making of the English Village: A Study in Historical Geography. Longman Scientific & Technical. ISBN 978-0-582-30143-6. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Time out of time’, when the barriers between this world and the next were down, the dead returned from the grave, and gods and strangers from the underworld walked abroad was a twice- yearly reality, on dates Christianised as All Hallows’ Eve and All Hallows’ Day.

- ^ O’Donnell, Hugh; Foley, Malcolm (18 December 2008). Treat or Trick? Halloween in a Globalising World. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-4438-0265-9.

Hutton (1996, 363) identifies Rhys as a key figure who, along with another Oxbridge academic, James Frazer, romanticised the notion of Samhain and exaggerated its influence on Halloween. Hutton argues that Rhys had no substantiated documentary evidence for claiming that Halloween was the Celtic new year, but inferred it from contemporary folklore in Wales and Ireland. Moreover, he argues that Rhys: «thought that [he] was vindicated when he paid a subsequent visit to the Isle of Man and found its people sometimes called 31 October New Year’s Night (Hog-unnaa) and practised customs which were usually associated with 31 December. In fact the flimsy nature of all this evidence ought to have been apparent from the start. The divinatory and purificatory rituals on 31 October could be explained by a connection to the most eerie of Christian feasts (All Saints) or by the fact that they ushered in the most dreaded of seasons. The many «Hog-unnaa» customs were also widely practised on the conventional New Year’s Eve, and Rhys was uncomfortably aware that they might simply have been transferred, in recent years, from then Hallowe’en, to increase merriment and fundraising on the latter. He got round this problem by asserting that in his opinion (based upon no evidence at all) the transfer had been the other way round.» … Hutton points out that Rhy’s unsubstantiated notions were further popularised by Frazer who used them to support an idea of his own, that Samhain, as well as being the origin of Halloween, had also been a pagan Celtic feast of the dead—a notion used to account for the element of ghosts, witches and other unworldly spirits commonly featured within Halloween. … Halloween’s preoccupation with the netherworld and with the supernatural owes more to the Christian festival of All Saints or All Souls, rather than vice versa.

- ^ Barr, Beth Allison (28 October 2016). «Guess what? Halloween is more Christian than Pagan». The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

It is the medieval Christian festivals of All Saints’ and All Souls’ that provide our firmest foundation for Halloween. From emphasizing dead souls (both good and evil), to decorating skeletons, lighting candles for processions, building bonfires to ward off evil spirits, organizing community feasts, and even encouraging carnival practices like costumes, the medieval and early modern traditions of «Hallowtide» fit well with our modern holiday. So what does this all mean? It means that when we celebrate Halloween, we are definitely participating in a tradition with deep historical roots. But, while those roots are firmly situated in the medieval Christian past, their historical connection to «paganism» is rather more tenuous.

- ^

- Moser, Stefan (29 October 2010). «Kein ‘Trick or Treat’ bei Salzburgs Kelten» (in German). Salzburger Nachrichten. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

Die Kelten haben gar nichts mit Halloween zu tun», entkräftet Stefan Moser, Direktor des Keltenmuseums Hallein, einen weit verbreiteten Mythos. Moser sieht die Ursprünge von Halloween insgesamt in einem christlichen Brauch, nicht in einem keltischen.

- Döring, Alois; Bolinius, Erich (31 October 2006), Samhain – Halloween – Allerheiligen (in German), FDP Emden,

Die lückenhaften religionsgeschichtlichen Überlieferungen, die auf die Neuzeit begrenzte historische Dimension der Halloween-Kultausprägung, vor allem auch die Halloween-Metaphorik legen nahe, daß wir umdenken müssen: Halloween geht nicht auf das heidnische Samhain zurück, sondern steht in Bezug zum christlichen Totengedenkfest Allerheiligen/ Allerseelen.

- Hörandner, Editha (2005). Halloween in der Steiermark und anderswo (in German). LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 8, 12, 30. ISBN 978-3-8258-8889-3.

Der Wunsch nach einer Tradition, deren Anfänge sich in grauer Vorzeit verlieren, ist bei Dachleuten wie laien gleichmäßig verbreitet. … Abgesehen von Irrtümern wie die Herleitung des Fests in ungebrochener Tradition («seit 2000 Jahren») ist eine mangelnde vertrautheit mit der heimischen Folklore festzustellen. Allerheiligen war lange vor der Halloween invasion ein wichtiger Brauchtermin und ist das ncoh heute. … So wie viele heimische Bräuche generell als fruchtbarkeitsbringend und dämonenaustreibend interpretiert werden, was trottz aller Aufklärungsarbeit nicht auszurotten ist, begegnet uns Halloween als …heidnisches Fest. Aber es wird nicht als solches inszeniert.

- Döring, Dr. Volkskundler Alois (2011). «Süßes, Saures – olle Kamellen? Ist Halloween schon wieder out?» (in German). Westdeutscher Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

Dr. Alois Döring ist wissenschaftlicher Referent für Volkskunde beim LVR-Institut für Landeskunde und Regionalgeschichte Bonn. Er schrieb zahlreiche Bücher über Bräuche im Rheinland, darunter das Nachschlagewerk «Rheinische Bräuche durch das Jahr». Darin widerspricht Döring der These, Halloween sei ursprünglich ein keltisch-heidnisches Totenfest. Vielmehr stamme Halloween von den britischen Inseln, der Begriff leite sich ab von «All Hallows eve», Abend vor Allerheiligen. Irische Einwanderer hätten das Fest nach Amerika gebracht, so Döring, von wo aus es als «amerikanischer» Brauch nach Europa zurückkehrte.

- Moser, Stefan (29 October 2010). «Kein ‘Trick or Treat’ bei Salzburgs Kelten» (in German). Salzburger Nachrichten. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ «All Hallows’ Eve». British Broadcasting Corporation. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

However, there are supporters of the view that Hallowe’en, as the eve of All Saints’ Day, originated entirely independently of Samhain and some question the existence of a specific pan-Celtic religious festival which took place on 31st October/1st November.

- ^ a b c d Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press, 2002. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-19-516896-8.

- ^ a b Brunvand, Jan (editor). American Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2006. p.749

- ^ a b Colavito, Jason. Knowing Fear: Science, Knowledge and the Development of the Horror Genre. McFarland, 2007. pp.151–152

- ^ a b c Rogers, Nicholas (2002). Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, p. 164. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516896-8

- ^ a b c Paul Fieldhouse (17 April 2017). Food, Feasts, and Faith: An Encyclopedia of Food Culture in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-61069-412-4.

- ^ Skog, Jason (2008). Teens in Finland. Capstone. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7565-3405-9.

Most funerals are Lutheran, and nearly 98 percent of all funerals take place in a church. It is customary to take pictures of funerals or even videotape them. To Finns, death is a part of the cycle of life, and a funeral is another special occasion worth remembering. In fact, during All Hallow’s Eve and Christmas Eve, cemeteries are known as valomeri, or seas of light. Finns visit cemeteries and light candles in remembrance of the deceased.

- ^ «All Hallows Eve Service» (PDF). Duke University. 31 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

About All Hallows Eve: Tonight is the eve of All Saints Day, the festival in the Church that recalls the faith and witness of the men and women who have come before us. The service celebrates our continuing communion with them, and memorializes the recently deceased. The early church followed the Jewish custom that a new day began at sundown; thus, feasts and festivals in the church were observed beginning the night before.

- ^ «The Christian Observances of Halloween». National Republic. 15: 33. 5 May 2009.

Among the European nations the beautiful custom of lighting candles for the dead was always a part of the «All Hallow’s Eve» festival.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-56854-011-5.

In most of Europe, Halloween is strictly a religious event. Sometimes in North America the church’s traditions are lost or confused.

- ^ Kernan, Joe (30 October 2013). «Not so spooky after all: The roots of Halloween are tamer than you think». Cranston Herald. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

By the early 20th century, Halloween, like Christmas, was commercialized. Pre-made costumes, decorations and special candy all became available. The Christian origins of the holiday were downplayed.

- ^ Braden, Donna R.; Village, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield (1988). Leisure and entertainment in America. Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village. ISBN 978-0-933728-32-5. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

Halloween, a holiday with religious origins but increasingly secularized as celebrated in America, came to assume major proportions as a children’s festivity.

- ^ Santino, p. 85

- ^ All Hallows’ Eve (Diana Swift), Anglican Journal

- ^ Mahon, Bríd (1991). Land of Milk and Honey: The Story of Traditional Irish Food & Drink. Poolbeg Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-85371-142-8.

The vigil of the feast is Halloween, the night when charms and incantations were powerful, when people looked into the future, and when feasting and merriment were ordained. Up to recent time this was a day of abstinence, when according to church ruling no flesh meat was allowed. Colcannon, apple cake and barm brack, as well as apples and nuts were part of the festive fare.

- ^ Fieldhouse, Paul (17 April 2017). Food, Feasts, and Faith: An Encyclopedia of Food Culture in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-61069-412-4. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

In Ireland, dishes based on potatoes and other vegetables were associated with Halloween, as meat was forbidden during the Catholic vigil and fast leading up to All Saint’s Day.

- ^ Luck, Steve (1998). «All Saints’ Day». The American Desk Encyclopedia. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-521465-9.

- ^ a b c «DOST: Hallow Evin». Dsl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ The A to Z of Anglicanism (Colin Buchanan), Scarecrow Press, p. 8

- ^ «All Hallows’ Eve». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press.

ealra halgena mæsseæfen

(Subscription or participating institution membership required.) - ^ «Halloween». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)